First things first, I’ve never read Silence by Shusaku Endo. I can at least say that I’ve heard of it, though, due to the fact that Martin Scorsese has been planning to make a movie based on it for what seems like forever.

Well, that and the fact that I had hoped to read it as a selection for the YIMCatholic Book Club, back in the day.

Back in the day. Wow, has it really been almost 3 years since I hosted a book to read here on the blog? Sheeeesh. A lot has happened since October 7, 2010. Truth be told, there are better folks reading, and writing about, books than me. Folks who actually know what they are talking about when it comes to discussing novels and such.

Enough lamenting the best laid plans of fallible bloggers. Let me tell how I came to read The Samurai by Shusaku Endo. It’s a minor miracle, in a way.

You know all those stories about saints who throw caution to the winds, pick up the Bible and flip it open randomly and decide that whatever passage they come upon is a hint from God about what they are supposed to do? It’s like that with me and choosing books to read. That’s how the nudge for me to become a Catholic moved into high gear.

Here’s the brief tale. It was one of the last days of our California vacation. I was minding my own business while the rest of my family was looking for bargains in a thrift store on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena, California. And not just any thrift store, but Out of the Closet, a small chain of donated merchandise stores operated by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation. Who knew they had books?

Who knew they had books like The Practice of the Presence of God by Brother Lawrence? That was the first gem I spied. Then I picked up other titles by C.S. Lewis, and by Tolkein too. When I spotted The Samurai by Endo, I heard the theme from Akira Kurosawa’s Roshomon playing in my head, and remembering my limited luggage space, I decided Tollers and Jack could wait, but Brother Lawrence and The Samurai were coming home with me. Seeing that my wife had picked up a couple of shirts for my youngest (baggage space limitations? Who has baggage space limitations?!) sealed the deal. That and the price ($1 a piece).

I’d already read Brother Lawrence’s classic, so I dove straight into 17th Century Japan. From the postscript, I learned that the novel is based on a true story. A story of powers and principalities, loyalty and betrayal, rivalry and faction. A story of competition among religious orders like I had never read before. You think the Jets and the Sharks were something? Try the Jesuits vs. the Franciscans. Well, the Jesuits against one plucky Franciscan missionary the likes of which I never imagined. Did I mention it is also the story of conversion? Boy howdy.

There are conversions of convenience, conversions by subterfuge, and conversions for political expedience. There are also surprising and authentic conversions, as well. There is palace intrigue, both in the palaces of kings and in the palaces of prelates. There is hope and misery, doubt and unbelief, as well as faith and a dawning realization about the way things really are when the affairs of men are weighed with a discerning eye, but one that is also repulsed by the pain-racked corpus of the God-Man the Christians worship, whose likeness is encountered everywhere along the way.

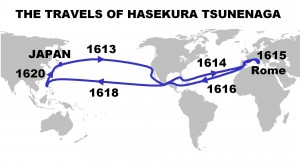

Lest you think all the action takes place in Japan, guess again. You will journey over land, and by sea, from the eastern shores of the Land of the Rising Sun, to the New World, and on further to Spain and even as far as the Eternal City, and back again.

Did I mention persecution yet? The story begins as the persecution of foreigners, long practiced in some parts of Japan, disregarded in others, ramps up to full force while the samurai, Lord Hasekura, and his three peers, leave the land they love behind on an unlikely mission as their Lords’ envoys, sent to open up trade directly with the viceroyalty in Nueva España.

I say unlikely because the samurai chosen in Endo’s novel are all low-level types. How low-level? Endo ranks them as lance-corporals, which is pretty low on the hierarchy of military ranks. This perhaps isn’t your idea of the way the warrior culture was, but that is the reality. Everyone can’t be the chieftain, you know. Having enjoyed seeing the film The Twilight Samurai, Endo’s authentic rendering of the life of a samurai grunt came to life easily for me. That and the fact that I spent a year in Japan myself.

Interestingly, both the characters of Father Velasco and Hasekura are addressed as “Lord.” In truth, I found myself wondering which character Endo means by the title of the book. Either man, or both? The actual samurai? Or the priest with the heart of a warrior, albeit one who wages spiritual war (unscrupulously, I might add) for the conquest of souls? Endo’s original proposed title (A Man Who Met a King) doesn’t even really clear things up in this regard. Nor does our learning that Fr. Velasco is a blood relation of Spanish conquistadores.

The reader comes to know these two characters very well, as the story is told interchangeably from both of their points of view. Endo slips between the two men’s narratives as deftly as an olympic relay sprinter passes a baton to a teammate.

Fr. Velasco’s approach to his mission is one fraught with moral dilemmas. When reflecting on his vocation he tells us,

Missionary work is like diplomacy. Indeed, it resembles the conquest of a foreign land. In missionary work, as in diplomacy, one must have recourse to subterfuge and strategy, threatening at times, compromising at others —if such tactics serve to advance the spreading of God’s word, I do not regard them as despicable or loathsome.

How’s that for Franciscan spirit, uh? Wait until you see what he has to say about the Jesuits! But Endo uses the character of Fr. Velasco to give us his keen insights on the faith too. This passage, for example, from when he is doubting his vocation as a missionary to Japan.

God is the center point of all order, the standard of all history. Beneath the currents of human history, God maps out another history in accordance with His own will. I am well aware of that fact. But all I have done, all I have planned, all I have dreamed, and even Japan itself are not part of that history conceived in the mind of God. have I been an outsider, a hindrance?

Yet during His lifetime even the Lord Jesus experienced the despair I am tasting. When on the cross He cried, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani? My God, my God, why has Thou forsaken me?’ Jesus must have been able to discern the will of God as I am unable to discern it now. But just before he gave up the ghost, Jesus conquered the despair. And He offered up to God the childlike words of trust, ‘Into Thy hands I commend my spirit.’ That much I know. And I would like to become such a person.

And the samurai himself experiences a great awakening during his lengthy sojourn around the world and back again. Lord Hasekura learns a truth about the “emaciated man,” Christ, and himself.

‘I suppose that somewhere in the hearts of men, there’s a yearning for someone who will be with you throughout your life, someone who will never betray you, never leave you — even if that someone is just a sick, mangy dog. That man became just such a miserable dog for the sake of mankind.’ The samurai repeated the words almost to himself.’Yes. That man became a dog who remains beside us.’

Before you go and get all cross-eyed with outrage, consider what St. Paul says of the Lord in his second letter to the Corinthians,

Christ never knew sin, and God made him into sin for us, so that in him we might be turned into the holiness of God.

You’re going to want to read this novel. One glance at the reviews on Amazon should convince you if I haven’t.

A few final words and then I’ll let you go. This is a human story wherein the relationships among the samurai and his servants, his family, his people, his land, and his earthly king, are played out with depth and realism. Lord Hasekura is a loyal subject who finds joy in serving his daimyo, even when he doesn’t understand why he is thrust into the role of envoy and he has no idea where he is going. When I was reading his inner thoughts as put down by Endo, I was often reminded of this prayer of Thomas Merton from his Thoughts On Solitude,

My LORD GOD, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road, though I may know nothing about it. Therefore I will trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.

Amen.

UPDATE: