Thanks to a recent game of family bingo, my five year old daughter is now the proud owner of a Santa gnome.

It currently has pride of place on the mantle above the fireplace in our living room.

She had her pick from the stack of bingo prizes at my mother-in-law’s house, but chose the gnome because 1)she saw a gnome in a neighbor’s yard recently and decided we needed one for our own yard and 2)she’s finally old enough to fall in love with Santa.

Don’t get me wrong, she understood the basics of Santa and Christmas for last year or two, or at least understood it enough for me to use “You don’t want to be on the naughty list, do you?” as a solid option for getting her to behave. But this is the first year she’s really embraced the magic of the season.

Her eyes light up whenever we see Santa Claus on TV or in the store.

She shouts “Look Daddy!” with the kind of joy only a child is capable of displaying whenever we drive by a house covered in Christmas lights.

Every morning since Thanksgiving she’s woken up and immediately asked, “Is it Christmas yet?”

Just today she saw the morning frost on my wife’s car which she mistook for snow and said, “Did Santa come last night?

I may not believe in Santa anymore, but her belief has rekindled a long lost love in my own heart as I watch the pure, unadulterated joy of Christmas wash over her every time she talks about the man with a belly that shakes like a bowl full of jelly.

Sadly, our shared love for Santa Claus has us both living in sin.

Or at least so says John Piper, one time mega-church pastor and all-time lover of bidding folks farewell on Twitter.

On his recent podcast, Piper accused parents of lying if they teach their children about Santa Claus.

According to The Christian Post, Piper said, “To present this myth as fact is not truthful to our children….Why would a Christian who has found in Jesus Christ the greatest treasure in the world trade it for anything else? Why would they — who see in the incarnation and life, death, resurrection, and reign of Jesus the most amazing story in the world — tell another story? Why would they replace it with such a non-gospel, pathetic myth like Santa Claus, whose message is ‘You better be good, and you better not cry’? I just can’t imagine it.”

Piper is letting his fundamentalism show here, but he’s not alone in his concern about Santa being a lie we tell our children. Perhaps surprisingly, on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum there are many progressive, liberal parents who also share Piper’s concern that teaching their children about Santa Claus is a form of lying that will only result in unnecessary pain when the day inevitably comes when their children discover that Santa isn’t “real.”

Look, I get it.

When I was a kid I held on to belief in the reality of Santa for dear life, far longer than I would like to admit. When I finally accepted the fact that there is no jolly man in a red suit living at the North Pole with the power to defy the laws of physics and space time, it was painful.

As a parent, I completely understand not wanting to ever cause our children pain or leave them jaded when they get older, questioning whether or not they can ever trust us again.

I get that.

I really do.

But while I may no longer consider The Santa Clause to be one of the most important and instructional documentaries of our time, I still have a soft spot in my heart for Santa Claus.

Not so much the person, but the myth.

I love myths.

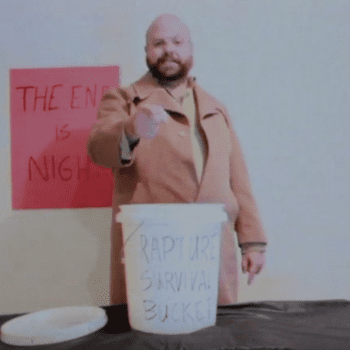

In fact, I just wrote a book called Unraptured in which I go on and on about my love for myths.

(And yes, I did just plug my book about end times theology in a post about Christmas [BrushShouldersOff.gif])

Myths have a transcendent power to speak to people across time, geography, and culture that “true stories” often don’t have. “True” stories are often bound by circumstance. They’re bound by their place in history, the people involved, preconceived ideas and prejudices about those people and places, and assumptions or ideas that may be radically foreign when told in a different place and time from their origin.

But myths aren’t like that.

Myths stand the test of time. And they’re wonderfully malleable. They transcend the place of their birth and spread out across the world, often being tweaked ever so slightly to adjust for the circumstances of the story teller while still retaining the same message.

Myths can even be powerful acts of political and cultural subversion. That is, after all, what we see in the book of Revelation. It’s an apocalyptic myth the presents a different, even subversive view of the world and a kingdom (the kingdom of God) that was radically different from the kingdom of the Roman empire. It’s vivid imagery of dragons, beasts, plagues, and stars falling from heaven were part of a subversive myth that transcends the history of the church with a promise to the faithful wherever and whenever they may be living that the powers and principalities of this world won’t last forever. That the beasts of oppression and exploitation have already been defeated. And that the kingdom of God that dawned in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus will soon come to completion.

Unfortunately, fundamentalism has fundamentally wrecked our ability to understand and appreciate the the truth power of myth.

The fundamentalism of folks like John Piper has tricked us into believing in a dichotomy between myth and truth.

In order for something to be “true,” we’re told, it has to take actually, really take place in documented, literal history. Because myth doesn’t play by those rules, we have been led to believe that “myth” is a just a synonym for “not true.”

But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

(Pun very much intended.)

In fact, myth often contains deeper truth than the “truth” of literal history. That’s because the truth of myths isn’t found in its historical details, but in its message and messages can be adapted, readapted, modeled and shaped to fit any time, place, or cultural context.

“Real” stories can’t do that. They’re bound by time and place and cultural context and as such the “truth” they contain is surprisingly limited. This is why myths have played such an important role in societies across the world and throughout history. Take for example the myth of Icarus. It’s not “true” at least not in the modern, fundamentalist sense that something must be literally true in order for it to be the truth. No one ever made wings that were able to carry them close to the sun. But the myth of Icarus is “true” nonetheless because the truth of Icaraus isn’t found in its historicity, but in its message and the lesson it teaches us, a lesson that can easily be understood whether we’re living in ancient Greece or modern day America.

Santa Claus is a myth and just like the myth of Icarus, it’s a myth that helps teach us important lessons.

Santa Claus teaches us about things like faith and obedience, kindness and generosity.

Even the milk and cookies we leave out for Santa teach a wonderful lesson about hospitality.

Is the myth of Santa Claus as important to the Church as the historical story of the birth of Jesus? Of course not, but that doesn’t make it untrue, nor does it make us liars if we teach our children the myth of Santa Claus. If anything, the myth of Santa Claus instills in our children important building blocks of faith. Those blocks certainly have to be built upon and aren’t strong enough to stand on their own, but they’re not a bad place to start with children whose world isn’t bound by the literal.

That’s why I teach my children the myth of Santa Claus without worrying that I might be lying to them.

I teach them because myths aren’t lies, they’re just another way, an often far more effective way of sharing the truth than dry historical facts.

Of course, I tell them about the birth of Jesus too and why Jesus, not Santa is the “reason for the season.” But Santa helps my toddlers conceptualize what faith and obedience, kindness and generosity, and even hospitality look like in a way that is not only easier for them to understand, but also sparks their imagination so that hopefully one day they’ll understand that Santa really is “real” and worth believing in – and emulating – no matter how old they get.

Maybe not real in the sense of living in a physical house at the North Pole they can travel to and visit themselves.

But real in the deeper, more important sense of what makes something true.

Real in the way myths helps to shape us all, kids from one to ninety-two, into better people.