- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

RELIGION LIBRARY

Hinduism

Vision for Society

On the most basic level, the vision for society articulated within Hinduism is that it should be dharmic, ordered. The most dominant way this order is created is through the caste system. Although in practice the caste system is often a means of oppression, it is in principle a vision of the perfectly ordered, perfectly symbiotic social body.

| CASTES | |

| Brahmin | (priestly caste) |

| Kshatriya | (traditionally warrior caste) |

| Vaishya | (traditionally caste of merchants and farmers) |

| Shudra | (manual laborers) |

At the top of the hierarchy of castes are the Brahmins. They are, traditionally, the ritual priests of the Hindu world. They perform the sacrifices that keep the gods satisfied, which, in turn, maintains dharma in the human realm. The next highest caste is that of the Kshatriyas, the so-called warrior caste whose dharma it is to maintain social order; this social order is necessary for the Brahmins to properly perform the rituals. Next come the Vaishyas, traditionally the merchants and cultivators; they contribute to dharma by providing the material needs of society. Finally, the Shudras, the lowest of the four major castes, the manual laborers who, in doing the "dirty work" of society create the conditions for purity necessary to perform the rituals.

The first articulation of this vision of society is often thought to be contained in the Purusha Shukta of the Rig Veda, where society is created through the sacrifice of the cosmic man, Purusha. There society is envisioned as a body, literally, in which all of the parts are necessary for the functioning of the whole. In this very early vision, the social distinctions are not negatively hierarchical, since each part of the body is equally necessary for the whole to function properly. Society functions because each member is, at any one time, doing precisely what is prescribed for him or her at birth.

The first articulation of this vision of society is often thought to be contained in the Purusha Shukta of the Rig Veda, where society is created through the sacrifice of the cosmic man, Purusha. There society is envisioned as a body, literally, in which all of the parts are necessary for the functioning of the whole. In this very early vision, the social distinctions are not negatively hierarchical, since each part of the body is equally necessary for the whole to function properly. Society functions because each member is, at any one time, doing precisely what is prescribed for him or her at birth.

Although this vision of society holds that all castes are equally necessary, they are certainly not, in practice, socially equal. The Brahmins are obviously at the top. However, social order, dharma, is absolutely dependent on the presence of a strong king, and much of the Dharmashastra literature that deals with issues of social order is about kingship. The ideal king is said to rule dharmically, which means with the perfect balance of fairness, compassion, and force. The god Rama—himself an avatara of Vishnu, the great "maintainer" or dharma—is depicted as the model king in the great Hindu epic, The Ramayana. In the Dharmashastra literature, the king is at the top of the Hindu social world, and all those below him are integrally connected so that the entire society functions properly.

| THE FOUR ASHRAMAS | |

| Ashrama (station in life) | Duties |

| Student | Learn duties of his caste |

| Householder | Raise a family |

| Forest dweller | Study sacred texts |

| Renouncer | Meditate |

The ashrama system developed as a further (and related) means of ordering society, by articulating a vision in which each person passes through a series of stages (ashramas) during their life. At any one time, a person fulfills his or her duty by doing what is appropriate at that time in life. One of the goals of the ashrama system is to resolve this tension between ethical and moral duty and ultimate salvation; it allows one to both act ethically in the world and attend to one's own salvation. The ashrama system, essentially, makes an ethical and moral space for attention to one's personal salvation. What the ashrama system does is create a balance between these two potentially opposing needs. One must first attend to one's ethical and moral duties, passing through the student (brachmacarya) and householder (grihastha) stages. Then, and only then, one can embark on a course of religious study—the forest dweller (vanaprastha) stage—and, eventually, ascetic renunciation of the world (the sannyasa stage).

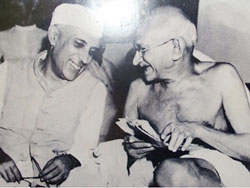

The nature of what, exactly, constitutes a dharmic society has been a matter of some tension in India, particularly after India gained independence in 1947. The Hindu world has historically been quite able to coexist with other religions: Buddhists, Jains, Sikhs, Muslims, Christians, and others. Although very ancient Hindu texts such as the Mahabharata describe a Hindu vision of India in which the entire subcontinent is understood as the sacred space of Hinduism, Hindus have mostly tolerated and even cooperated with people of other religions. In modern India, Mahatma Gandhi was a staunch advocate of Indian home rule, and his Satyagraha campaign led the way to ousting the British from India, yet he was not in any sense a Hindu exclusivist.  Indeed, Gandhi fundamentally believed in the possibility, and even the necessity, of peaceful coexistence between India's many religions. India's first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, and other early leaders of independent India promoted a secular India that made room for all religions, not just Hinduism. Certainly this model of society was built on the foundation of dharma, but it was a broad, inclusivist understanding of what is dharmic.

Indeed, Gandhi fundamentally believed in the possibility, and even the necessity, of peaceful coexistence between India's many religions. India's first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, and other early leaders of independent India promoted a secular India that made room for all religions, not just Hinduism. Certainly this model of society was built on the foundation of dharma, but it was a broad, inclusivist understanding of what is dharmic.

Not all Hindus have held such a view. Gandhi himself was assassinated by an extremist Hindu who radically rejected Gandhi's view. There have been loud and insistent voices advocating an exclusively Hindu India as the only model of a truly dharmic society. Beginning in the 1980s, these voices became particularly forceful with the emergence of powerful political groups—the Bharatiya Janata Party and Vishva Hindu Parishad are two of the most prominent—advocating the purification of India. For them, this would mean essentially removing all foreign elements from what they see as the sacred Hindu homeland. Their understanding of a dharmic society, then, is a purely Hindu one, and the presence of other religions pollutes this vision.

Not all Hindus have held such a view. Gandhi himself was assassinated by an extremist Hindu who radically rejected Gandhi's view. There have been loud and insistent voices advocating an exclusively Hindu India as the only model of a truly dharmic society. Beginning in the 1980s, these voices became particularly forceful with the emergence of powerful political groups—the Bharatiya Janata Party and Vishva Hindu Parishad are two of the most prominent—advocating the purification of India. For them, this would mean essentially removing all foreign elements from what they see as the sacred Hindu homeland. Their understanding of a dharmic society, then, is a purely Hindu one, and the presence of other religions pollutes this vision.

This rather extreme exclusivist view has led to serious tensions and at times horrific violence between Hindus and Muslims in particular. Although this is by no means a majority view within Hinduism, this form of Hindu exclusivism is a powerful social and political force in India, often drowning out the more moderate and more tolerant mainstream voices.

Study Questions:

1. How does the caste system help create social order?

2. What does the Rig Veda contribute to the Hindu vision for society?

3. How is religious pluralism viewed within India?