- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

RELIGION LIBRARY

Judaism

Gender and Sexuality

Men and women are equally obliged by the Torah's system of Divine commandments, or mitzvot. However, on account of their traditional domestic, and especially their "natural" child-rearing obligations, women were exempted by rabbinic law from any obligation to perform positive commandments that are "time-bound," most notably participation in public prayer services at specifically mandated times. Women were also excluded, and often discouraged, from the obligation to study Torah, which is commonly viewed in rabbinical theology as the pinnacle of religious devotion.

As a result of this exclusion of women from the public and most elevated of religious obligations, classical rabbinical Judaism—including contemporary Orthodox Judaism—is often depicted as being essentially patriarchal, or even sexist, in nature. Compounding this perception is the fact that ecclesiastical authority has, since biblical times, been the exclusive domain of males, from the priests and Levites of ancient Israel who administered the rituals in the Jerusalem Temple, to the rabbis and cantors who today serve as the spiritual leaders of traditional, or Orthodox, congregations. Moreover, while the other denominations of Judaism all practice egalitarianism in public worship today, Orthodox synagogue services remain strictly gender separated, with women usually relegated to the sides, rear, or balcony of the sanctuary, while men alone are permitted to lead the services, preach sermons, and be "called up" to bless, and read from, the Torah and Prophets.

As a result of this exclusion of women from the public and most elevated of religious obligations, classical rabbinical Judaism—including contemporary Orthodox Judaism—is often depicted as being essentially patriarchal, or even sexist, in nature. Compounding this perception is the fact that ecclesiastical authority has, since biblical times, been the exclusive domain of males, from the priests and Levites of ancient Israel who administered the rituals in the Jerusalem Temple, to the rabbis and cantors who today serve as the spiritual leaders of traditional, or Orthodox, congregations. Moreover, while the other denominations of Judaism all practice egalitarianism in public worship today, Orthodox synagogue services remain strictly gender separated, with women usually relegated to the sides, rear, or balcony of the sanctuary, while men alone are permitted to lead the services, preach sermons, and be "called up" to bless, and read from, the Torah and Prophets.

At the same time, women do play a vital role in traditional Jewish domestic and family life, most notably in assuring adherence to the dietary laws and ensuring that the many domestic Shabbat and festival rituals (most notably candle lighting), meals, and customs are prepared and conducted in accordance with Jewish law. Women are also entrusted to ensure adherence to the laws of taharat ha-mishpacha, or family purity.

At the same time, women do play a vital role in traditional Jewish domestic and family life, most notably in assuring adherence to the dietary laws and ensuring that the many domestic Shabbat and festival rituals (most notably candle lighting), meals, and customs are prepared and conducted in accordance with Jewish law. Women are also entrusted to ensure adherence to the laws of taharat ha-mishpacha, or family purity.

Since the 2nd-century codification of the Mishnah, the rabbis have endeavored to soften some of the biblical laws most prejudicial to women through ingenious scriptural exegesis and the introduction of new legal institutions. The Jewish laws of marriage and divorce offer a key case study in such strategies employed by the rabbis to adjust, if not quite equalize, the status of women over the course of centuries. In ancient Israel, as the Bible makes quite evident, wives were considered the property of their husbands. A man could, for example, simply and abruptly divorce his wife, just as easily as he had "acquired" her. This is dramatized by the simple and brief biblical legislation regarding the procedure for divorcing one's wife, which to this day presents a formidable obstacle in achieving gender equity in Jewish family law: "A man takes a wife and possesses her. If she fails to please him because he finds in her something unseemly, he shall then write her a bill of divorcement, hand it to her and send her away from his house" (Deuteronomy 24:1).

Since the 2nd-century codification of the Mishnah, the rabbis have endeavored to soften some of the biblical laws most prejudicial to women through ingenious scriptural exegesis and the introduction of new legal institutions. The Jewish laws of marriage and divorce offer a key case study in such strategies employed by the rabbis to adjust, if not quite equalize, the status of women over the course of centuries. In ancient Israel, as the Bible makes quite evident, wives were considered the property of their husbands. A man could, for example, simply and abruptly divorce his wife, just as easily as he had "acquired" her. This is dramatized by the simple and brief biblical legislation regarding the procedure for divorcing one's wife, which to this day presents a formidable obstacle in achieving gender equity in Jewish family law: "A man takes a wife and possesses her. If she fails to please him because he finds in her something unseemly, he shall then write her a bill of divorcement, hand it to her and send her away from his house" (Deuteronomy 24:1).

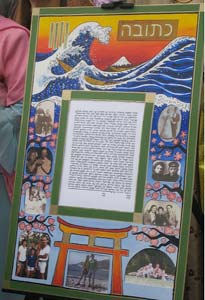

The history of extensive rabbinic legislation regarding these laws of divorce documents the introduction of significant protections of women from the abuse to which a literal application of this biblical system so clearly exposes them. To begin with, the rabbis required men to provide their wives with a marriage contract, known as a ketubah, in which they pledge to "sustain, respect, love, feed and protect (their wives)...." The ketubah, an Aramaic document that is handed to the bride under the chupah, or wedding canopy, additionally provides the woman with a substantial "pension" should her husband predecease or divorce her.

The history of extensive rabbinic legislation regarding these laws of divorce documents the introduction of significant protections of women from the abuse to which a literal application of this biblical system so clearly exposes them. To begin with, the rabbis required men to provide their wives with a marriage contract, known as a ketubah, in which they pledge to "sustain, respect, love, feed and protect (their wives)...." The ketubah, an Aramaic document that is handed to the bride under the chupah, or wedding canopy, additionally provides the woman with a substantial "pension" should her husband predecease or divorce her.

Another major challenge inheres in the fact that, according to the Bible, only a man can initiate divorce proceedings, as there is nothing in the Torah anticipating a woman divorcing her husband. Moreover, the treatment of divorce in Deuteronomy stipulates entirely subjective and exclusively male standards as constituting grounds for divorce. These problems were addressed through exacting rabbinical exegesis, which had the cumulative effect of narrowing the interpretation of "something unseemly" to sexual promiscuity or infidelity, and simultaneously widening the requirements for a valid "writ of separation" by creating elaborate scribal and juridical procedures governing the issuance of a legally binding divorce document, known in Hebrew as a get.

Another major challenge inheres in the fact that, according to the Bible, only a man can initiate divorce proceedings, as there is nothing in the Torah anticipating a woman divorcing her husband. Moreover, the treatment of divorce in Deuteronomy stipulates entirely subjective and exclusively male standards as constituting grounds for divorce. These problems were addressed through exacting rabbinical exegesis, which had the cumulative effect of narrowing the interpretation of "something unseemly" to sexual promiscuity or infidelity, and simultaneously widening the requirements for a valid "writ of separation" by creating elaborate scribal and juridical procedures governing the issuance of a legally binding divorce document, known in Hebrew as a get.

While rabbinic law was unable entirely to circumvent the biblical standard by which only the husband could initiate divorce proceedings, rabbinical courts since the early medieval period were provided with wide latitude to compel, even by physical coercion when all else failed, abusive or neglectful husbands to grant their wives a get. In the late 10th century, the leading rabbinical scholar of Franco-Germany, R. Gershom of Mainz, issued an ordinance against "throwing the divorce" at a woman against her will, which effectively required the wife's consent to accept the get in the presence of a rabbinical court. R. Gershom also issued a universal Jewish ban on polygamy that has remained in force ever since among all Ashkenazic Jews.

Judaism has, since biblical times, maintained a generally positive view of licit sexuality. Sexual relations within marriage are considered not only entirely natural, but obligatory and even holy. In striking contrast to the more ascetic classical Christian sexual ethos, rabbinical Judaism encouraged regular sexual relations, in particular on Shabbat. Unlike those who enter Christian priestly or monastic orders, Jewish clergy are not celibate; quite the contrary, both rabbis and cantors are expected to marry and have families like all other members of the Jewish community.

Judaism has, since biblical times, maintained a generally positive view of licit sexuality. Sexual relations within marriage are considered not only entirely natural, but obligatory and even holy. In striking contrast to the more ascetic classical Christian sexual ethos, rabbinical Judaism encouraged regular sexual relations, in particular on Shabbat. Unlike those who enter Christian priestly or monastic orders, Jewish clergy are not celibate; quite the contrary, both rabbis and cantors are expected to marry and have families like all other members of the Jewish community.

While there is a variety of attitudes to, and religious interpretations of, human sexuality among both medieval and modern Jewish philosophers and mystics, there is no school of Jewish thought that advocates sexual abstemiousness in the name of any higher religious calling. While this positive attitude to human sexuality was generally beneficial to women, it did tend to prevent the emergence of women religious clerics, saints, or mystics, since Judaism rejected the very notion that a woman might abstain from her procreative duties to devote herself to a purely spiritual calling. On the other hand, the positive Jewish attitude to licit sexuality within the context of marriage resulted in Jewish law including, among the obligations of Jewish husbands, attending to the sexual satisfaction of their wives, an obligation considered on par with housing, physical protection, clothing, and financial support.

While one of their earliest innovations was the initiation of "family-seating" at religious services—in contrast to the strict separation of the sexes in Orthodox services—it has only been since the last quarter of the 20th century that the Reform and Conservative movements have allowed for the ordination of women as rabbis. The first female Reform rabbi was ordained by the Hebrew Union College in 1972; and it was only in 1983 that the Conservative Movement's Jewish Theological Seminary ordained its first woman rabbi. Since then, however, women have very rapidly risen in the ranks of Reform and Conservative rabbis and cantors. Today the numbers of women studying for both rabbinical ordination and cantorial diplomas at all the non-Orthodox seminaries exceed those of men.

While one of their earliest innovations was the initiation of "family-seating" at religious services—in contrast to the strict separation of the sexes in Orthodox services—it has only been since the last quarter of the 20th century that the Reform and Conservative movements have allowed for the ordination of women as rabbis. The first female Reform rabbi was ordained by the Hebrew Union College in 1972; and it was only in 1983 that the Conservative Movement's Jewish Theological Seminary ordained its first woman rabbi. Since then, however, women have very rapidly risen in the ranks of Reform and Conservative rabbis and cantors. Today the numbers of women studying for both rabbinical ordination and cantorial diplomas at all the non-Orthodox seminaries exceed those of men.

While Orthodox Judaism does not sanction the ordination of rabbis and precludes women from chanting public services, within a small very liberal faction of Modern Orthodoxy, egalitarian congregations have begun to emerge. In these, women and men alternate in leading the services and preaching, although the women are not officially referred to as rabbis and cantors. A few Orthodox synagogues in the United States and Israel today employ female "rabbinic interns," many of whose duties, such as teaching Torah and rendering halakhic decisions, are the same as those of traditional rabbis. In March 2009, the controversial Modern Orthodox rabbi and activist, Avi Weiss of Riverdale, New York, conferred the equivalent of rabbinical ordination upon a graduate of the Drisha Institute, an Orthodox women's seminary in New York City. While the future of women as spiritual leaders within Orthodoxy is impossible to predict with certainty, the gender-egalitarian trends of the larger society are clearly impacting this most traditional wing of Judaism.

While the established policy of the Reform movement has long been to ordain and employ in its congregations openly gay and lesbian persons as both rabbis and cantors, the status of homosexuals as religious leaders currently remains a matter of heated dispute within the Conservative movement. While the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary of America decided, in 2007, to ordain openly gay rabbis and cantors, the movement's synagogue council, the United Synagogues of America, has not enforced an equal employment policy with regard to gay clergy. Each congregation remains free to establish its own standards regarding the hiring of gay rabbis and cantors.

Orthodox Judaism, following the Levitical laws that unambiguously prohibit male homosexual relations and depict them as an "abomination," adamantly refuses to grant ordination to homosexuals or to employ openly gay clergy.

Study Questions:

1. How does time play a role in deciding the participation of women within the Jewish tradition?

2. How do gender roles continue to influence segregation in Jewish worship?

3. Describe the process of divorce within the Jewish community. Why might it seem one-sided?

4. How is sexuality celebrated within Judaism?

5. Are homosexuals welcomed within Jewish leadership? Explain.