- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

RELIGION LIBRARY

Judaism

Exploration and Conquest

While 19th- and early 20th-century Jewish historiography on the Middle Ages portrayed the Jews as powerless in an era of political and religious insecurity, recent scholarship has shown that the rabbis were actually pragmatic political as well as religious leaders who took an active role in promoting Jewish interests in the non-Jewish world. They accomplished this by creating a quasi-sovereign Jewish empire in exile based on external as well as internal sources of power. Although the Jews derived their relative power from their host governments, the rabbis legitimized it based on Talmudic legal principles.

First, they argued that the entire community is a collective court whose authority is based on an implied social contract binding upon all its members, and this court is able to expropriate property and can enact emergency legislation when necessary. While the rabbis debated the role of this court, they agreed that the ignorant masses must be excluded from power.

The most important justification for Jewish self-government in exile was the halakhic or legal doctrine, dina de malkhuta dina, "the law of the kingdom is the law." Yet instead of passively ceding complete legal authority to the king, the rabbis interpreted the "law of the kingdom" to refer only to matters of taxation. Thus, they assumed that this was a contract between two sovereign powers wherein each had to give up a portion of their power in order to live in peace: the rabbis would cede authority for taxation to the king, while the king would cede authority to the Jews to govern themselves in all other areas. Ironically, rather than acting as subservient political subjects to the king, the Jews were laying the legal groundwork for their own quasi-autonomous empire in exile.

While the rabbis legitimized their political authority in the Jewish community vis-a-vis foreign rulers based on internal Talmudic resources, they strategically negotiated alliances with both religious and secular rulers that enabled them to develop a certain level of political power and autonomy outside the Jewish community in the medieval political hierarchy. On the one hand, the religious authorities of Christianity and Islam designated the Jews as second-class citizens with no political power because of their inferior theological status in relation to God; on the other hand, they granted them political protection because of their unique association with the Hebrew scriptures, texts considered sacred by both religious communities and upon which both base their identities.

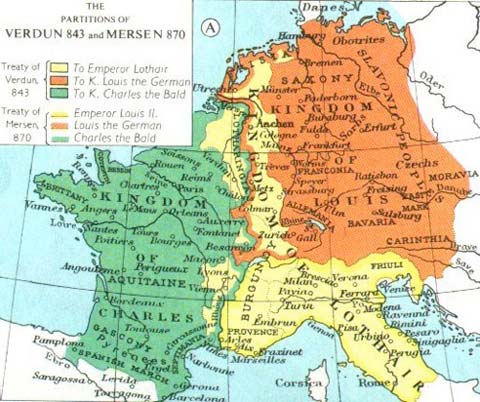

While cultivating relations with religious authorities in 9th-10th century Muslim Iraq and later Christian forces of the reconquista, Jews also initiated alliances with secular rulers like the French and German Kings from the Carolingian period until the 11th century and the Polish nobility of the 15th-16th centuries. This political pragmatism, along with their status as an urban merchant class, enabled them to rise above the peasant class and approach the level of knights and burghers. They had freedom of movement and, in many medieval towns in Germany, France, and Spain, were eligible for full citizenship. Ironically, the term that was used to describe the medieval sociopolitical status of the Jews was servi camerae or "serfs of the royal chamber," which, despite its negative connotation, actually enabled Jews to pay taxes directly to the king instead of to the local lords. While there was always a danger of financial extortion from the king, Jews received royal protection and were treated as free people.

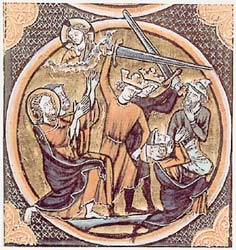

In contrast, the medieval Jews faced the greatest persecution when it was initiated by anti-government mass movements or popular uprisings. This was evident during the first Crusades in 1096 when overzealous knights and angry mobs went against explicit prohibitions in secular and ecclesiastical law not to kill Jews, who had a theologically protected status. Instead of going directly to Jerusalem to liberate Christian holy places from the Seljuk Turks, as they were called upon to do by Pope Urban II, these roving bands marched into the Rhineland and attacked Jewish communities in Speyer, Worms, Mainz, Trier, and Regensburg. The Jews responded by either taking up arms against the Crusaders or, in many cases, turning their weapons on themselves rather than converting to Christianity. This act of kiddush ha-Shem, or martyrdom, became associated with the active use of weapons rather than a passive resistance to their fate.

In contrast, the medieval Jews faced the greatest persecution when it was initiated by anti-government mass movements or popular uprisings. This was evident during the first Crusades in 1096 when overzealous knights and angry mobs went against explicit prohibitions in secular and ecclesiastical law not to kill Jews, who had a theologically protected status. Instead of going directly to Jerusalem to liberate Christian holy places from the Seljuk Turks, as they were called upon to do by Pope Urban II, these roving bands marched into the Rhineland and attacked Jewish communities in Speyer, Worms, Mainz, Trier, and Regensburg. The Jews responded by either taking up arms against the Crusaders or, in many cases, turning their weapons on themselves rather than converting to Christianity. This act of kiddush ha-Shem, or martyrdom, became associated with the active use of weapons rather than a passive resistance to their fate.

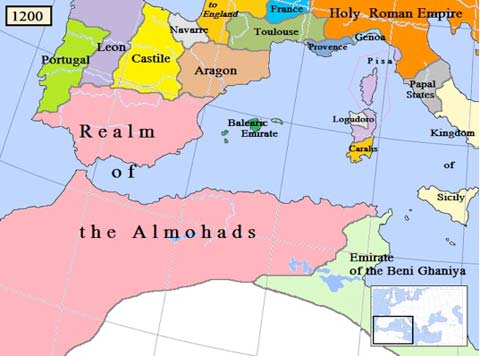

Later in the 12th century, the Muslim extremist group, Almohades, "Proclaimers of the Unity of Allah," responded to the Christian reconquista in the 12th century by invading Spain to defend Islamic purity and domination. These treated the Jews in Africa and Iberia harshly and forced them to flee en masse into Christian conquered areas. Yet the Jews were not just pawns in a military chess match between Muslims and Christians. They were authorized by Christian kings to defend themselves from their enemies and were exempt from punishment for any opponents that they killed in battle.

Obviously, the medieval Jews did not have the political and military power to sufficiently defend themselves without foreign political alliances or to achieve territorial conquest. However, by carefully navigating the medieval political landscape, the rabbis were able to maintain a secure foothold for the Jewish community despite reoccurring political and religious insecurity. Ultimately, they were able to create a semi-autonomous political and religious empire by presenting themselves as the surrogate leaders for the ancient Jewish commonwealth in exile until its reestablishment in the messianic age.

Study Questions:

1. How were rabbis both religious and political leaders?

2. What can be said about the relationship between halakhic law and medieval royalty?

3. Why were Jews permitted to travel freely, and receive royal protection?

4. Who persecuted medieval Jews? How did they survive?