- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

RELIGION LIBRARY

Judaism

Missions and Expansion

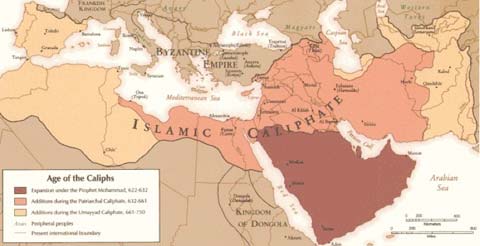

As religious and social conditions worsened for the Jews in Palestine under the control of Christian Rome, the center of Jewish life was transferred from the land of Israel to Babylonia, the seat of the new Muslim empire. During this period of Muslim rule from the 7th-13th centuries, Jews encountered Greek philosophy, medicine, physics, astronomy, and mathematics. They also studied the Quran, Muslim poetry, philology, biography, history, and mysticism, illustrating a linguistic, philosophical, and religious synthesis that is best described as "Judeo-Arabic culture." Yet this synthesis not only occurred in the elite, intellectual realm, but also at the popular level in the sense that most Jews were indistinguishable from their Muslim neighbors in terms of names, dress, and language.

However, despite the relative comfort of Jews in Muslim society, they were still conscious of their unique heritage and destiny as a people that placed them at odds with their Muslim contemporaries in the public sphere who questioned their loyalty to the Muslim state. Ironically, it was the Muslim authorities that provided the Jews with a protective status or dhimma if they agreed to pay a tax and keep a low profile. Indeed, by conquering the Persian and Byzantine empires, their Muslim conquerors enabled the Jews, for the first time since the Hellenistic period, to comprise one political, economic, and cultural Judeo-Arabic empire stretching from western Asia through north Africa to the Iberian peninsula—the largest pre-modern Jewish community in the world.

The split of the Muslim empire into regional factions led to the demise of the Babylonian Jewish community and the move westward to Spain, northwest Africa, and Egypt. During this period between the 11th-15th centuries, the Sephardic Jewish community flourished in Spain while representing the entire Judeo-Arabic world in the areas of biblical exegesis, philosophy, law, secular and religious poetry, and Kabbalah or Jewish mysticism.

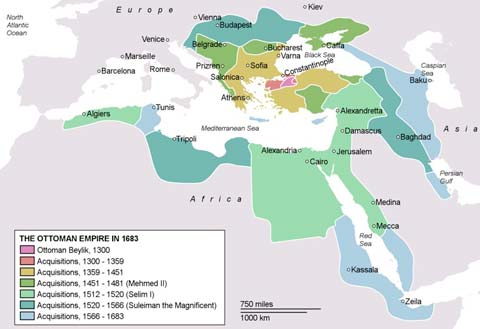

However from the 12th-15th centuries, Christians engaged in a "reconquest" of Spain culminating in many forced conversions and finally expulsion of the Jews in 1492. In their attempts to remain crypto-Jews, many conversos (converts to Christianity) practiced Jewish rituals in secret. Yet as a result, these ambiguous Jews were never fully accepted in either the Jewish or Christian communities. The Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain were forced to find refuge in Italy and countries of the Ottoman Empire including Turkey, the Balkans, north Africa, Morocco, and Palestine, eventually establishing colonies in western and central European cities like Hamburg, London, and Amsterdam.

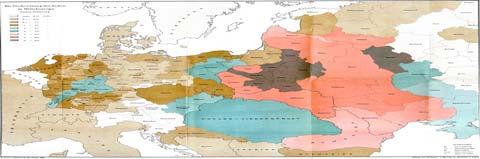

Earlier in the 9th century, small groups of Jews migrated as international merchants from Italy to France and Germany, bringing with them the law and customs of their Palestinian and Babylonian forbearers. These Jews comprised the Ashkenazic community, Jews of German origin, while encompassing all of northern and eventually eastern Europe. As Christianity became dominant in northern Europe, these Ashkenazic Jews developed a symbiotic relationship with Christians driven by a dialectic between fascination and aversion toward one another.

While medieval Jews and Christians often interacted publically in social, economic, or even religious situations, their leaders would condemn these efforts, while at the same time inverting the symbols or theological claims of the other in order to demonstrate their superiority. An example of this medieval Jewish-Christian dialectic on the Christian side was the creation of the "blood libel" accusation, by Christian cleric Thomas of Monmouth in 1150, that Jews ritually murdered a twelve-year-old Christian boy, William of Norwich, by crucifixion.

This mythical Christian reenactment of the passion led to the creation of newly martyred saints like William of Norwich and was the basis for a malicious antisemitic myth lasting into the 20th century. In this myth, Christians mixed both Jewish and Christian motifs together in the following way: First, they accused Jews of tying a rope around the victim's head that resembled the Jewish tefilin shel rosh, the ritual head phylacteries worn for daily prayer. Yet this rope around the victim's head also simulated the thorny crown on Jesus' head during the crucifixion. Next, the Christian authors of this myth drew upon biblical motifs associated with the Book of Esther, including the evil Haman's casting of purim or lots to determine when to kill the

This mythical Christian reenactment of the passion led to the creation of newly martyred saints like William of Norwich and was the basis for a malicious antisemitic myth lasting into the 20th century. In this myth, Christians mixed both Jewish and Christian motifs together in the following way: First, they accused Jews of tying a rope around the victim's head that resembled the Jewish tefilin shel rosh, the ritual head phylacteries worn for daily prayer. Yet this rope around the victim's head also simulated the thorny crown on Jesus' head during the crucifixion. Next, the Christian authors of this myth drew upon biblical motifs associated with the Book of Esther, including the evil Haman's casting of purim or lots to determine when to kill the  Persian Jews and his eventual hanging on a stake for his attempted crime. However in the blood libel legend, the Christian authors jumbled these symbols by accusing Jews of annually casting lots to determine when to shed Christian blood and portraying them as hanging Christian boys on posts.

Persian Jews and his eventual hanging on a stake for his attempted crime. However in the blood libel legend, the Christian authors jumbled these symbols by accusing Jews of annually casting lots to determine when to shed Christian blood and portraying them as hanging Christian boys on posts.

On the other hand, medieval Ashkenazic Jews created their own hagiographies as if to reclaim the power of the passion narrative for themselves. One such fictional narrative about Rabbi Amnon of Mainz expresses the ambivalence of many Jews toward conversion to Christianity. After repeated attempts by a local bishop to convert him, Rabbi Amnon asked the bishop for three days to decide. Unwilling to give the Christians a religious victory on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, he decided to become a Jewish martyr and his body was dismembered. Before he died, he composed a piyyut or liturgical poem. Just as Jesus instructed his disciples to spread his gospel three days after the crucifixion,  Rabbi Amnon appeared three days after his death before the leader of the Mainz community and told him to publically distribute the prayer he wrote. In this way, the medieval Ashkenazic Jewish community emerged victorious over Christianity by supplanting their Messiah with another Jewish Christ-figure experiencing redemptive suffering, whose teachings would live on after his death.

Rabbi Amnon appeared three days after his death before the leader of the Mainz community and told him to publically distribute the prayer he wrote. In this way, the medieval Ashkenazic Jewish community emerged victorious over Christianity by supplanting their Messiah with another Jewish Christ-figure experiencing redemptive suffering, whose teachings would live on after his death.

These dueling Jewish and Christian counter-narratives demonstrate the degree of attraction each community had for the other's sacred motifs, while at the same time using them as weapons against the other. Like the Sephardic Jews in Muslim and later Christian Iberia, the Ashkenazic Jews engaged in a type of cultural adaptation that was part of a larger strategy of resistance in which they constructed their identities by actively negotiating the ideas of the majority culture and adjusting them to fit their ever-changing circumstances.

Study Questions:

1. Why was assimilation essential to Judaism's survival?

2. How were political events associated with Islam closely linked to the spread of Judaism?

3. Describe the relationship between commerce and Judaism's spread.

4. Who was Rabbi Amnon? What did he contribute to Judaism's spread?