- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

RELIGION LIBRARY

Judaism

Influences

While the rabbis traced their identities back to the Israelites, they portrayed them in ideal terms as a community that set itself apart, maintained its own names and language, and resisted intermarriage. This ideal portrayal is borne out by the Israelites' own composite biblical narrative comprising the books of Genesis through Joshua, in which there are a later series of ethnocentric "folk traditions" weaving together many originally individual narratives during the Babylonian exile. Yet it is this type of theologically driven, nostalgic historiography by the editors of the biblical narrative and later rabbis that masks the multicultural origins of this people Israel.

Drawing upon archaeological and textual evidence, scholars have presented a rather different picture. They argue that the community of Israel most likely emerged historically out of a loosely defined coalition of Canaanite city dwellers and migrating herders in the early part of the second millennium B.C.E. as part of a larger Amorite migration into Syria-Palestine, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. Instead of resisting foreign names, languages, and intermarriages—as the rabbis claimed—it appears that the Israelite nation was culturally and perhaps ethnically descended from the Canaanite population. This type of syncretism—the blending of different religious and cultural influences—is demonstrated in the name "Israel," which actually stems from a Canaanite word, along with other names like the Egyptian word Moses. Moreover, because of the Israelites' close association with the Canaanite and other ancient near eastern cultures, their Hebrew language is based on the Phoenician alphabet and closely related to the early Canaanite language, Ugaritic.

As a result of its multicultural beginnings, the biblical narrative is full of intermarriages despite legal bans to the contrary: Joseph and the Egyptian Asnat, Boaz's marriage to Ruth the Moabite (an ancestor of King David), and King Solomon's many foreign wives, including the Ammonite woman who gave birth to King Solomon's successor, Rehoboam. In fact, it could be argued that intermarriage was actually a central component in the political ideology of the Israelite monarchy in the sense that by sharing the blood line of its vanquished foes, the Moabites and the Ammonites, later Judean kings could solidify the Davidic dynasty.

As a result of its multicultural beginnings, the biblical narrative is full of intermarriages despite legal bans to the contrary: Joseph and the Egyptian Asnat, Boaz's marriage to Ruth the Moabite (an ancestor of King David), and King Solomon's many foreign wives, including the Ammonite woman who gave birth to King Solomon's successor, Rehoboam. In fact, it could be argued that intermarriage was actually a central component in the political ideology of the Israelite monarchy in the sense that by sharing the blood line of its vanquished foes, the Moabites and the Ammonites, later Judean kings could solidify the Davidic dynasty.

| Opening lines of the Enuma Elish |

| When the sky above was not named, And the earth beneath did not yet bear a name, And the primeval Apsû, who begat them, And chaos, Tiamat, the mother of them both, Their waters were mingled together, And no field was formed, no marsh was to be seen; When of the gods none had been called into being. |

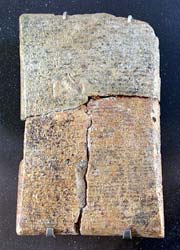

One can see foreign religious influence in the creation myths and law codes of ancient Israel. When examining the creation story of Genesis 1 along with other myths about the origins of the cosmos in the Psalms, there is a clear parallel with the Babylonian creation myth, Enuma Elish, which predates the biblical account of creation. Both the biblical and Babylonian creation myths demonstrate a common theological perception in the ancient near east that the universe is comprised of various primordial, cosmic forces representing different aspects of nature, i.e., the sea and the sky. In order to make sense of the world and their place in it, the Israelites, along with their ancient near eastern neighbors, believed that the universe literally came together as a unified cosmos only after these natural forces competed with one another for supremacy.

| Divine fiat: God is transcendent and creates by command |

| In the beginning of God's creating the skies and the earth, when the earth had been shapeless and formless, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and God's spirit was hovering on the face of the water, God said, "Let there be light!" |

The later Priestly editor of the Hebrew scriptures tried to distinguish the biblical creation myth from those of the Babylonians. He attempted to portray a God who is completely transcendent or above other natural forces and creates by divine fiat. One can detect, however, in Genesis 1 an implicit allusion to these cosmic forces in the primordial waters of creation. The more explicit images in the Psalms depict God fighting mythical sea creatures like Tannin and Leviathan in order to gain mastery over the cosmos. This cosmic battle is similar to the one between Marduk and Tiamat in the Enuma Elish. There is also a clear convergence between the later flood story in Genesis 6 and another Babylonian flood epic, Gilgamesh, wherein there is a flood that destroys the world as a divine punishment for human injustice.

The more explicit images in the Psalms depict God fighting mythical sea creatures like Tannin and Leviathan in order to gain mastery over the cosmos. This cosmic battle is similar to the one between Marduk and Tiamat in the Enuma Elish. There is also a clear convergence between the later flood story in Genesis 6 and another Babylonian flood epic, Gilgamesh, wherein there is a flood that destroys the world as a divine punishment for human injustice.

There is also evidence indicating a direct connection between Israelite and Hittite cultures in the 14th century B.C.E. In an attempt to describe their encounter with God at Mt. Sinai, the later Israelite authors of the Torah developed the religious motif of covenant based on the concept of a treaty between a King and his conquered vassals.  Just as the Hittite King Mursalis II demanded loyalty from his vassal Duppi-Teshub of Amurru in exchange for protection, the Israelite God enters into a covenant with Israel that is contingent upon observance of commandments in exchange for divine affiliation. The resulting Israelite law code has clear parallels with the laws and personal statutes of the 18th-century B.C.E. code of the Babylonian King Hammurabi.

Just as the Hittite King Mursalis II demanded loyalty from his vassal Duppi-Teshub of Amurru in exchange for protection, the Israelite God enters into a covenant with Israel that is contingent upon observance of commandments in exchange for divine affiliation. The resulting Israelite law code has clear parallels with the laws and personal statutes of the 18th-century B.C.E. code of the Babylonian King Hammurabi.

We also see this religious syncretism coupled with an intellectual adaptation of Greek "strategies of existence" during the later Hellenistic period, most conspicuously illustrated in the scriptural books of Ecclesiastes in 250 B.C.E. and Daniel in the 2nd century B.C.E.

We also see this religious syncretism coupled with an intellectual adaptation of Greek "strategies of existence" during the later Hellenistic period, most conspicuously illustrated in the scriptural books of Ecclesiastes in 250 B.C.E. and Daniel in the 2nd century B.C.E. The teaching of Ecclesiastes reflects the sense of predeterminism and detachment associated with the Greek philosophy of Stoicism. It instructs the reader not to become too emotionally attached to what happens in life because it is all predetermined by God. Moreover, Ecclesiastes's portrayal of an utterly transcendent and seemingly absent God resembles the Greek concept of impersonal fate.

The teaching of Ecclesiastes reflects the sense of predeterminism and detachment associated with the Greek philosophy of Stoicism. It instructs the reader not to become too emotionally attached to what happens in life because it is all predetermined by God. Moreover, Ecclesiastes's portrayal of an utterly transcendent and seemingly absent God resembles the Greek concept of impersonal fate.

Next, while the book of Daniel is based on the figure of Daniel in the Ugaritic Aqhat Epic, the book was most likely written during the Hellenistic period in approximately 164 B.C.E. Moreover, Daniel's apocalyptic visions in chapters 7-12 incorporate Hellenistic intellectual and religious influences like Platonic dualism, and his reference to secrets of the future or hidden knowledge possessed by God only revealed to the "elect" reflects the ideas of Hellenistic mystery cults and gnosticism. Finally, the book's portrayal of individual resurrection, unprecedented in the Hebrew scriptures, is a definite reflection of Hellenistic culture that would be developed in both Jewish and Christian cultures following the destruction of the Second Temple.

| Daniel -- Double Chiasm | |

| Hebrew | Chaldean |

|

Chapter 1

Historical Prologue A. Chapter 2

Kingdom Prophecies Image of king B. Chapter 3

Trials of God's People Image Worship/Fiery Furnace C. Chapter 4

King's Prophecy Nebuchadnezzar Tree cut down C. Chapter 5

King's Prophecy Bolshazzar Writing on the Wall B. Chapter 6

Trials of God's People Worship King/Lion's Den A. Chapter 7

Kingdom Prophecies Wild Beasts |

A. Chapter 8

Kingdom Prophecies Sacrificial Animals B. Chapter 9a

Trials of God's People Prayer of forgiveness C. Chapter 9:25

King's Prophecy Decree to rebuild Jerusalem D. Chapter 9:26

Messiah Dies Alone C. Chapter 9:25

King's Prophecy Decree to destroy Jerusalem B. Chapter 9:27

Trials of God's People Mourning for the Temple A. Chapter 10

Kingdom Prophecies King of the North/King of the South Chapter 12b

Prophetic Epilogue |

Indeed, Judaism and Christianity emerged as defined religious communities in relation to each other during the 2nd century C.E. Both drew upon a common religious discourse inherited from the biblical and Second Temple periods that defined a people Israel and its relation to God. Each religious community identified itself with its eponymous ancestors Jacob and Esau fighting for the blessing of their father, while both defined themselves as the younger brother supplanting the older.

Whereas it has been historically assumed that Christianity evolved out of Judaism, one could argue that rabbinic Judaism was actually influenced by its slightly older brother Christianity. One could argue that in response to the formation of "orthodox" Christianity in the 2nd century C.E., the rabbis began to legitimize their leadership by establishing a chain of authority parallel to the apostolic tradition, while inventing the concept of minut or heresy and associating it with the early Jewish-Christians. This attempt at religious boundary construction by the rabbis belied the actual co-emergence of Judaism and Christianity in antiquity and reflected an ongoing tension between these religious cultures over who were really God's chosen people that would not abate until after the Holocaust.

Study Questions:

1. How does the “folk narrative” differ from the scholarly narrative of Judaism's influences?

2. What was the role of interracial marriage in Judaism's beginnings?

3. How is Judaism's creation story similar to the myth of the Babylonians? How was it differentiated?

4. Did Christianity later form out of Judaism, or Judaism out of Christianity? Why?