- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

RELIGION LIBRARY

Sunni Islam

Sacred Narratives

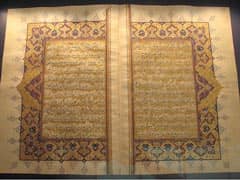

There are several genres of literature in the Sunni tradition that could qualify as sacred narratives. It is important to keep in mind that foundational narratives, such as the prophetic mission of Muhammad, the revelation of the Quran, the stories of biblical prophets,  creation, and the like as contained in the Quran, are common to all sects of Islam. In the Sunni tradition, an historical narrative surrounding the institution of the caliphates and the elections of Abu Bakr, Umar ibn al-Khattab, and Uthman, also became important foundational narratives for the bolstering of Sunni legitimacy and political authority.

creation, and the like as contained in the Quran, are common to all sects of Islam. In the Sunni tradition, an historical narrative surrounding the institution of the caliphates and the elections of Abu Bakr, Umar ibn al-Khattab, and Uthman, also became important foundational narratives for the bolstering of Sunni legitimacy and political authority.

Early Islamic culture, deeply steeped in a long tradition of oral history in the Arabian Peninsula, preserved tales of battle days, genealogies, poetry, and glorious reputations of historical heroes; this tendency did not end with the advent of Islam. With the growth and institutionalization of Sunni political hierarchies, along with the transition to written culture, oral culture filtered into several literary and historical genres. Chief among these was biographical literature, or sira.

It soon became clear that the most important biography would be that of Muhammad himself, whose Sira (his biography came to be known simply as "The Sira" in a terminological sense) was crucial for the legitimization and clarification of his prophetic mission. The oldest extant biography of the Prophet was by a man named Ibn Ishaq, and was compiled (probably from earlier materials) around 150 years after Muhammad's death. That version was later edited by Ibn Hisham in the 9th century. Although the Prophet's biography came to be seen as the sine qua non of the biographical genre, there is evidence that there was also some amount of history-writing (historiography) as well as biographical writing before his life story was put into final form. The narrative of Muhammad's life was central to the development of Sunni tradition because it preserved and narrated the life story of the founder of Islam.

Biography expanded enormously as a category. It would prove to be particularly important for Sunni Islam, which places so much emphasis on the legitimacy of the first three caliphs. In law and in the study of hadith, a study of the first generations of Muslims meant pinning down the essentials of their biographies in order to assess their legitimacy as transmitters of the sayings and deeds of Muhammad. Furthermore, the legitimacy and pious authority of the Companions, another tenet in Sunni Islam and one made poignant by the conflict with Shi‘ism, depended upon knowing and disseminating the biographies of these important men and women.

Eventually, other genres grew out of the need to preserve the memory of the first generations of Muslims. Beyond mere biographical notices, a genre called manaqib, or "virtues literature," and another called fada'il or "religious merits literature" became a vital part of the Sunni historical tradition. These holy biographies (hagiographies, from the Greek Hagios, holy) went far beyond the bare facts of this or that Companion's life, and included length descriptions of their piety, bravery, asceticism (zuhd in Arabic), and general excellence in character. Like the Christian version of the same literary genre, Islamic hagiography sought to extol the virtues of heroes of the past, constituting another set of sacred narratives about the generations succeeding the initial dawn of Islam.

Eventually, other genres grew out of the need to preserve the memory of the first generations of Muslims. Beyond mere biographical notices, a genre called manaqib, or "virtues literature," and another called fada'il or "religious merits literature" became a vital part of the Sunni historical tradition. These holy biographies (hagiographies, from the Greek Hagios, holy) went far beyond the bare facts of this or that Companion's life, and included length descriptions of their piety, bravery, asceticism (zuhd in Arabic), and general excellence in character. Like the Christian version of the same literary genre, Islamic hagiography sought to extol the virtues of heroes of the past, constituting another set of sacred narratives about the generations succeeding the initial dawn of Islam.

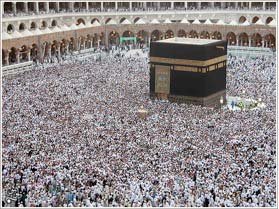

The fada'il genre expanded yet again. By the 10th century C.E., the religious merit of places as well as people was finding a niche in the burgeoning Sunni tradition. Syrian Sunnis in particular were hard-pressed to rival the foundational cities of Mecca and Medina, not to mention the long-standing sanctity of Jerusalem among all three Abrahamic faiths. They went to great lengths to collect and disseminate sacred stories about the Holiness of the Syria, and especially of Damascus.

The fada'il genre expanded yet again. By the 10th century C.E., the religious merit of places as well as people was finding a niche in the burgeoning Sunni tradition. Syrian Sunnis in particular were hard-pressed to rival the foundational cities of Mecca and Medina, not to mention the long-standing sanctity of Jerusalem among all three Abrahamic faiths. They went to great lengths to collect and disseminate sacred stories about the Holiness of the Syria, and especially of Damascus.

Many great cities and even small villages, by this time, were receiving their own treatment in the hands of historians who sought to prove that their regions and localities were of eternal as well as earthly importance. A city like Mecca was likened to the navel of the universe, or the center of the cosmos. Syria was likened to a human body, with Damascus as the heart, animating the whole region. Medina was consistently referred to as a city of light, for its initial welcoming of the Prophet upon his emigration from Mecca. A small town outside of Damascus, like Darayya, could boast that several dozen Companions of Muhammad had lived and been buried there, adding to that city's holiness.

Many great cities and even small villages, by this time, were receiving their own treatment in the hands of historians who sought to prove that their regions and localities were of eternal as well as earthly importance. A city like Mecca was likened to the navel of the universe, or the center of the cosmos. Syria was likened to a human body, with Damascus as the heart, animating the whole region. Medina was consistently referred to as a city of light, for its initial welcoming of the Prophet upon his emigration from Mecca. A small town outside of Damascus, like Darayya, could boast that several dozen Companions of Muhammad had lived and been buried there, adding to that city's holiness.

As with other sacred narratives about people and places, in the Sunni tradition the evolution and dissemination of these types of stories accompanied a burgeoning practice of local pilgrimages in addition to the major Islamic pilgrimage made annually to Mecca. Text and practice went hand in hand in this regard, displaying the interweaving of tradition and material culture.

As with other sacred narratives about people and places, in the Sunni tradition the evolution and dissemination of these types of stories accompanied a burgeoning practice of local pilgrimages in addition to the major Islamic pilgrimage made annually to Mecca. Text and practice went hand in hand in this regard, displaying the interweaving of tradition and material culture.

Study Questions:

1. What sacred texts do Sunnis share with all of Islam? What narrative separated it?

2. Describe the relationship between biography and Sunni legitimation of power.

3. Why was the fada'il expansion to include places important to ritual within Islam?