“Determined now her tomb to build,

Her ample skirt with stones she filled,

And dropped a heap on Carron-more;

Then stepped one thousand yards to Loar,

And dropped another goodly heap;

And then with one prodigious leap,

Gained carrion-beg; and on its height

Displayed the wonders of her might.”

~ Jonathan Swift (1667 – 1745)

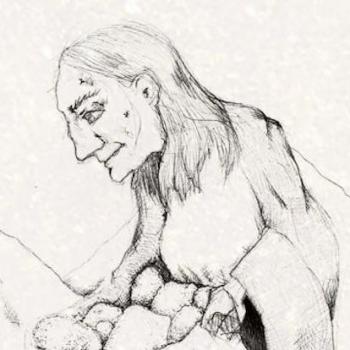

The giant blue form of the Cailleach straddles the British Isles; she is the unforgiving crone of winter, the benevolent earth-shaping giantess and the guardian of the sacred wells. Like the land itself, the Cailleach changes shape, sometimes appearing as a beautiful young maiden, sometimes as a hideous old woman and sometimes as a legendary giantess. She is one of the most ancient spirits, shaping the Earth, ruling the wilderness as Lady of the Beasts, she is a foreteller of doom, a Water Witch and simultaneously both malevolent and benevolent – and ultimately she is the bestower of sovereignty. As recently as the early twentieth century stories of the Cailleach were recorded in parish church records, and traces of her origins can be traced to Portugal, and even further back with tentative links to the enigmatic figure of the earliest known temple structures: Sansuna, the giant goddess credited with building the Ggantija temples on the island of Gozo, Neolithic structures older than both Stonehenge and the Egyptian Pyramids!

From these ancient Mediterranean origins her legends, and possibly her priesthood, migrated with Celtic tribes from Spain to Ireland, to Scotland and to the Isle of Man. Her influence spread into the rest of Britain too, with clues still evident in place-names and local folklore recorded in England, Wales and Jersey, as well as through shared motifs found in Brittany and Scandinavia. Written evidence can be found in the writings of Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny and in Irish texts such as the Leabhar Gabhala Érenn (Book of Invasions) and the ninth century text Historia Brittonum, which was written by a Welsh monk. Ultimately, it is in the landscape and the stories of the landscape, where we found the essence of this formidable giant blue hag – and indeed, sometimes hags (plural), as we encounter stories suggesting that at times there were more than one Cailleach, which combined with other evidence suggests that the term ‘Cailleach’ may at times have been used as a title for a cult of wise women as there are stories which suggest that at times there were more than one Cailleach and that indeed the term ‘Cailleach’ may have been used for a cult of wise women (Priestesses?) who lived, worked and taught in the British Isles.

The most frequently found motif associated with the Cailleach is in her role as shaper of the land, she does this through a variety of actions – quite often through the dropping of stones which she carries either in her apron or on her head, and sometimes through the accidental flooding of holy wells which form mountains, caves, lochs, lakes and rivers – many of which still bear her name today. The best examples of such land-shaping deeds can be found in the local legends of Scotland. One such example which has particular amusing and bawdy twist was recorded by Eleanor Hull in her article Legends and Traditions of the Cailleach Bheara or Old Woman (Hag) of Beare, in it is recorded the mythic creation of the Scottish island of Ailsa Craig. The story goes that one day a French sailor sailed his boat between the legs of the Cailleach as she was wading through the ocean carrying a load of rocks in her apron. The sail of his ship brushed her inner thigh and the surprise touch to such an intimate part of her anatomy caused her to drop some of the rocks with a start, resulting in the formation of the island.

Another rock-dropping story was recorded by Miller in Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland, where we also find the Cailleach in association with other giants who it was believed ruled the British Isles in the distant past. One of these tribes of giant beings lived in what is now Ross-shire in the highlands of Scotland, and they were well known for their incredible strength and kinsfolk, the most of famous of whom were the giants Gog-Magog and the Cailleach-Mhore (Great Cailleach). This particular Cailleach was famed for being strong even amongst this mightily-hewed tribe and is attributed with the shaping of the entire landscape in this area. The legend tells us that the Cailleach Mhore was walking over the hills with a pannier of earth and rocks on her back, when she paused for breath and stopped at the site of Ben-Vaichard. She stood gazing around her, and as she did so the pannier gave way with its contents pouring out over the landscape. The Cailleach Mhore cursed as her load was scattered and when the dust cleared the new hills had been formed by the earth and rocks she had been carrying.

There are many such examples from all over Scotland and Ireland, and elsewhere attributing the shaping of the land to the Cailleach. The Cailleach even had a hand in the shaping of the most famous of Scottish lakes, Loch Ness, known today for its famed mythical beast ‘The Loch Ness Monster’. The story was recorded in Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend and has a clear parallel in one of the tales recorded in the Irish Dindshenchas (History of Places) about the Morrígan, who turned a maiden called Odras into a pool of water in her anger when she discovered that the maiden allowed a bull to mate with one of the cows in the Morrigan’s supernatural cow herd. We are told that the Cailleach had two wells in Inverness-shire, and it was her duty to cap and open these every day, but tired of having to spread her efforts; she hired a maiden to remove the smaller cap of the well at sunrise and replace it again at sunset. The maid, Nessa, was late reaching the well one night and as she approached the well she saw the water flowing from it towards her furiously. She ran for her life, leaving the well uncapped and the Cailleach saw this happening from her home at the top of Ben Nevis. In her anger, she cursed Nessa for neglecting her duty that she would have to run forever and never leave the water. At once Nessa was transformed into a river and a Loch, which today is the river Ness and Loch Ness. It is said that each year, on the anniversary of her transformation, Nessa emerges from the loch and sings a sad song, to the most beautiful melody, to the Moon, lamenting her misfortune. I wonder how many sightings there are of Nessa when she performs her song each year, and whether those who have the fortune to hear about her misfortune for being late, develop a stronger sense of being punctual and vigilant when it comes to their own duties!

It is interesting to note that when the Cailleach was asked the secret of her age, she always gave an answer associated with the Sidhe (fairy folk). She declared that she never carried the dirt of one place beyond that of another place without washing her feet, thereby not taking the earth from one territory to another. This practice is one commonly associated with fairies, but could also represent a stricture connected with a priesthood. When we started to look into the fairy connection, it was clear this was a common theme with the Cailleach, who was described as the Fairy Queen at times, particularly in the Scottish highlands (and also at times in Ireland). Thus we found that at one point in her ancient history, the Cailleach Béarra lived on the summit of Cnoc na Sidhe (Hill of the Fairy Mound), where the wind always blew. Milk and butter also frequently turned up in stories associated with her, recalling brownies and other house spirits. The fairy cows of the Cailleach are a common theme in Irish tales, matched by her herd of deer in the Scottish ones.

I should like to end this introduction to the mighty and enduring Cailleach with a verse from a song recorded in Gaelic in 1823 which emphasised her position:

“Tremble mortal, at my power,

Leave my sacred dominion!

Ere I cause the heavens lower,

And whelm thee with a fearful shower,

For sport to my fairy minions!”

Further reading:

Cailleach: Hag of Beira, O’Sullivan, 2009

Visions of the Cailleach, d’Este & Rankine, 2009

The Book of the Cailleach, Ó Crualaoich, 2006