This is Day 16 of the 2017 #30Days30Writers Ramadan series – June 11, 2017

By Dalia Mogahed

For me, very few experiences inspire more awe or more pleasure then staring up at a clear starry night in the desert. Suddenly, everything is in perspective. H.G. Wells put it best when he said, “Looking at these stars suddenly dwarfed my own troubles.”

While the stars are always present, it takes special conditions to view their full splendor. Though we think of light as a means to see, it is precisely the dazzle of neon signs and street lights that desensitizes and distracts our eyes, depriving us from enjoying the stars. In the desert, when man-made light is a journey away, we suddenly have access to the spell binding beauty of the night sky.

To me, the Ramadan fast is about taking away what desensitizes and distracts our hearts so we can access spiritual realities hidden to us by easy fixes and immediate gratification.

This Ramadan especially I’ve been reflecting on how abstaining from food, water and sex for 16 hours a day for a month impacts people in a world that commands all of us to “obey your thirst.”

How does this practice of putting conscience over comfort shape our thinking? How does it alter our patterns? How should it change us?

The Quran describes the Ramadan fast as a practice “prescribed to you as it was to those before you so as to enable your taqwa.” The word “taqwa,” often translated as piety or God-consciousness, comes from a root word that means to protect or shield from harm.

Synthesizing between its understood theological meaning and its linguistic origin, taqwa can best be described as the act of protecting against ethical transgressions through an active and deliberate mindfulness of God. It signifies a deepened awareness of spiritual realities, seeing the world as it truly is, with eyes unclouded by the delusions of the false idols of ego and arrogance.

But how exactly does that work? How does the act of restraining yourself from physical impulses for a prescribed period of time enable leading a God-centered life? I think of it this way: By limiting access to easy comforts, we are forced to dig deeper, to discover hidden sanctuaries that require a quieting of our appetites, the removal of distractions, a temporary desert, to be seen.

Fasting forces a break from the norm, a necessary discomfort to wake up a heart lulled to sleep by lazy habits and false sanctuaries.

In some ways, all of Islam’s pillars impose a break of some kind from the hypnotic inertia of life’s mundane hum, but always return us to that human messiness as actors, not bystanders or isolated monks.

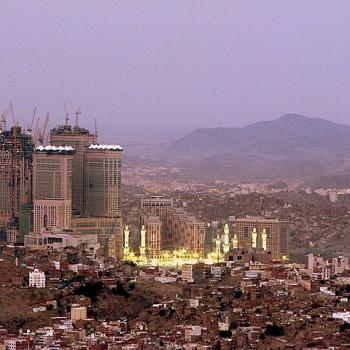

The five daily prayers disconnect us temporarily from our daily routine so we can connect with God. The yearly Ramadan fast disconnects us temporarily from our creature comforts so we can access a more profound sanctuary. The annual paying of the purifying alms as a right to the poor (zakat) disconnects us from some of the wealth we have been made custodians over to break our attachments to materialism. And, once in a life time, the Hajj breaks us away completely from our status, wealth, comforts and familiar routine — returning us without sin, a clean slate and a second chance.

Even the first pillar, the bearing witness to God’s singular oneness and Muhammad’s prophethood, breaks us away from the distracting deities of money, ego and status.

No, fasting isn’t easy. It isn’t shiny and entertaining. It isn’t always comfortable or convenient. It requires self-restraint and resolve. But growth rarely follows periods of ease, and neon signs blind us from the stars.

Dalia Mogahed is the director of research at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. She served on President Obama’s Advisory Council on Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships in 2009, advising the president on how faith-based organizations can help government solve persistent social problems. She is a former director of the Gallup Center for Muslim Studies, where her surveys of Muslim opinion skewered myths and stereotypes while illuminating the varied attitudes of Muslims toward politics, religion, and gender issues — all of which were covered in her 2008 book with John Esposito, Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think.