The latest post over at Wild Fox Zen reminded me of a bit of my recent academic work: Kantian ethics.

And before the collective moan resonates around the world, let me share a quote which will begin my chapter on the subject:

Many accept my view that Kant is a more appealing moral philosopher on my reading than on the traditional one. They may even reluctantly admit that it is better supported by the texts than they thought it could be. But they still resist, because they feel their philosophical world deprived of a significant inhabitant – namely, the stiff, inhuman, moralistic Prussian ogre everyone knows by the name Immanuel Kant.

– Allen Wood

Part of studying Kant, it seems, is disabusing oneself (and eventually others) of the many misguided notions that exist about the man and his thought. He was caricatured in his own lifetime and in every subsequent generation. Perhaps it’s just easier to do this than to actually read his works. (Admittedly, it is.) But just as I mentioned recently that getting into Buddhist thought and practice has helped me open up to the many varieties and nuances of other religions, it has done the same regarding philosophies that once seemed so easy to pigeon-hole.

So What is Enlightenment?

In 1784, at the age of 60 and just hitting his proverbial ‘stride’ as a philosopher, Immanuel Kant wrote an essay as a response to a literary journal (think the New Yorker) “Answering the question: What is Enlightenment?” (German: “Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?”)

Of course it has nothing to do with Bodhi, or awakening, which can cause much gnashing of teeth amongst academic-ish Buddhists. Enlightenment instead refers to an age or period of time in Europe when things seemed to be changing and unfolding at an unprecedented rate. After hundreds of years of scholasticism, barbarism, disease and warfare, things seemed to be changing for the better. Science, exploration, colonization, trade, and new technologies were creating an ever-larger middle and educated class. (It should go without saying that this was a pretty horrible time for many people outside of Europe – colonialism brought more warfare, disease, dehumanization, and so on than many area had experienced ever in history). Kant himself came from very humble beginnings as the son of a saddle maker. But this -for Europeans- was an age of upward mobility…

But Kant’s answer seems to resonate (with me at least) even today. And of course, with Buddhist quotes like “be an island (or lamp) onto yourself,” “each person is an heir to his/her own karma (actions),” as well as the whole Kalama Sutta and widely regarded notion that in Buddhism, “it’s up to you – Buddha can’t help you” (Pure Land aside).

Enlightenment is the human being’s emancipation from its self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to make use of one’s intellect without the direction of another. This immaturity is self-incurred when its cause does not lie in a lack of intellect, but rather in a lack of resolve and courage to make use of one’s intellect without the direction of another. ‘‘Sapere aude! Have the courage to make use of your own intellect!’’ is hence the motto of enlightenment.

Idleness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large segment of humankind, even after nature has long since set it free from foreign direction (naturaliter maiorennes), is nonetheless content to remain immature for life; and these are also the reasons why it is so easy for others to set themselves up as their guardians. It is so comfortable to be immature. If I have a book that reasons for me, a pastor who acts as my conscience, a physician who determines my diet for me, etc., then I need not make any effort myself. It is not necessary that I think if I can just pay; others will take such irksome business upon themselves for me. [1]

“Enlightenment is the human being’s emancipation from its self-incurred immaturity.”

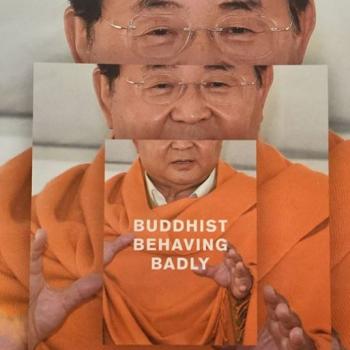

Of course I am biased, but I can’t help thinking that the Buddha would have agreed. And another person I think would have agreed, one of the great heroes of the twentieth century, is this guy:

Viktor Frankl, author of Man’s Search for Meaning, a book documenting his experiences in a Nazi concentration camp and the power of meaning for keeping prisoners alive.

The thing tying these all together, I think, is Frankl’s airplane analogy. Perhaps the Buddha, Kant, Frankl and others will exhort ideals that seem beyond the reach of ordinary people. But it is exactly that ideal, and the striving we ordinary beings undertake to attain it, that allows us to become fully human. Think a bit about the “cross-winds” of society toward complacency, sensual enjoyment, blame, etc…

I’m always a fan of sitting back and smiling at what is. Whether that’s a toothache (which seems to be my latest malady), or the sun illuminating the froth on a fresh cup of coffee, it just is. And if we cannot stop and find at least some beauty, or something to laugh about in this very moment, we should know that we have more work to do (as I often find out…).

But the ideal of striving should also never be far from one’s mind. The MidWest couch potato sitting in front of the TV, perfectly at ease with what is, isn’t a Zen master. He (or, occasionally she) has lost the balance.

[1] Ak 8:33-42, reprinted in (Kant, Toward Perpetual Peace and Other Essays, 2006, pp. 17-23).