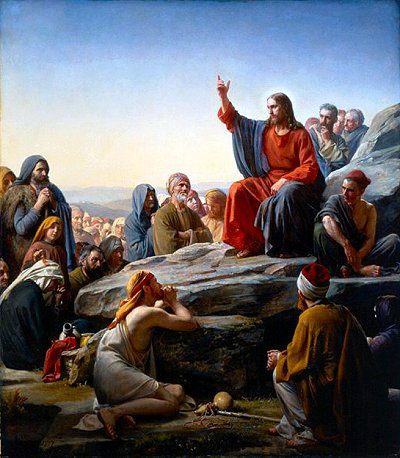

Christ says “blessed are the poor,” (Luke 6:20) and the splendor of his words is that they contain a quality of invisibility, a capacity to be ignored and forgotten at a rate far excelling the human usual. Indeed, there are few words that demand more action and yet have the grand effect of no one doing anything at all, not for any inarticulacy in Christ, but for timidity in man.

“Blessed are the peacemakers,” says Christ, and few believe he wants us to cheer on these peaceful people while remaining contentious sons of bitches ourselves. No, we understand that inherent to his blessing is his demand to become peacemakers. Blessed are the meek, he says, and once again, we understand we are to become meek, not nod in appreciation of meek people. But “blessed are the poor,” and suddenly the understanding shifts. No longer do our ears ring with the command to become. Instead, we are filled with the warm, comforting image of Christ blessing the poor, showering his benevolence on those others who are poor, patting the heads of the sorely afflicted — a constituency we may or may not be part of.

I say “we” because I am too frightened to say “I,” for this is my inability to deal with the radicalism of Christ. Far easier if his words present no demand upon my existence, and his blessing upon the poor remains no more than an interesting note about what God is into these days, as in, “Just so you know, and as long as we’re all on this Mount, poor people are great. Now then, back to my explicit synthesis of the methods by which you will be saved.” No, all human existence is a bad attempt at being blessed by God, and thus when God himself says “blessed are the poor,” he is advocating our poverty, a poverty which will be for us a divine blessing, that is, our salvation.

I say “we” because I am too frightened to say “I,” for this is my inability to deal with the radicalism of Christ. Far easier if his words present no demand upon my existence, and his blessing upon the poor remains no more than an interesting note about what God is into these days, as in, “Just so you know, and as long as we’re all on this Mount, poor people are great. Now then, back to my explicit synthesis of the methods by which you will be saved.” No, all human existence is a bad attempt at being blessed by God, and thus when God himself says “blessed are the poor,” he is advocating our poverty, a poverty which will be for us a divine blessing, that is, our salvation.

Why can’t we hear him? Perhaps we just don’t want to be poor. Or perhaps it lies in the added words of the Gospel of Matthew: “Blessed are the poor in spirit.” Typically taken, we say this “in spirit” refers to attitude, to the point that I might equate Christ’s words with “blessed are the poor in attitude.” Christ is not saying we cannot be rich, the idea goes, only that we must have an attitude of poverty towards our riches. Blessed is the man with the mental disposition of being poor, a man unassuming of his riches who — though he might own Costa Rica — nevertheless remains humble.

Now I would hardly argue that a mental disposition of poverty is anything but an improvement over pride and greed, but it is not an adequate response to Christ’s demand.

The relegation of poverty to the spirit does not cushion the crush of Christ’s words, but further radicalizes them. The spirit — or in the original Greek, the pneuma — is not an attitude. It is the innermost core of man, the locus of life, freedom and existence from which acts. It is the incommunicable interior of the person, expressed through his exterior — through language, gesture, and the body in general. The confusion between spirit and attitude is caused, in part, by our abysmal love for pop psychology and new age religion, where the “spiritual” is fluffy in comparison to the physical — the spirit the source of ethereal emotions and vague, hazy feelings. This notion of the spiritual is precisely what allows people to say “I’m not religious, I’m spiritual,” which translates roughly to “I have all these deep feels, and do nothing.” Blessed are the poor in spirit, we the hip hear, and thus turn inwards so as to render some secret, intangible spirit-space poor, a process achieved with nothing more than a slight grimace and a change in attitude.

But the spirit is not fluffy. The spirit is the animating principle of the body. The spirit, according to Kierkegaard, is the self. The spiritual is known through the physical because it animates the physical. I know someone is courageous — which is spiritual — through their actions — which manifest themselves in the physical. I know a woman is in love — which is a spiritual reality — through her actions, that is, through what she does. I know a man is evil — which is a spiritual state — through his actions. Call it the soul, subjectivity, interiority, self, and we will quibble over the distinctions later. The spiritual manifests itself by body-slamming the physical into movement, a process we call acting.

This seems to be what James is getting at when he says:

Suppose a brother or a sister is without clothes and daily food. If one of you says to them, “Go in peace; keep warm and well fed,” but does nothing about their physical needs, what good is it? In the same way, faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead.

James says that any faith — an interior, spiritual reality — which does not manifest itself in exterior, objective action is dead. So too, a poverty of spirit that remains an interior attitude of poverty without manifesting itself in actions of poverty, in becoming poor, is dead. Christ was calling us to more, not less, when he blessed the poor in spirit. In fact, he cut us off from pretending that poverty could be anything but a total poverty that manifests itself in our objective, physical existence. He slapped us away from at the apocalypse appealing to an attitude of poverty that can never be a being poor.

So next time, let’s talk about being poor.