There is much to be learned about ancient literacy in the fine book edited by William Johnson and Holt Parker, as I said in the previous post, and one of the overall impressions the book leaves is the growing suspicion that William Harris, the guru on levels of literacy in the ancient world (no more than 10-20%) was wrong, indeed badly wrong if we take into account all different sorts of literacies. As Rosalind Thomas says in the opening essay in the volume “it is misleading to talk simply in these terms, or to talk of percentages of literates, for that presupposes a certain definition of literacy, one that irons out variety and complexity.” (p. 14).

If one is referring to what classics scholars call literary literacy— the ability to read, write, comment, and show knowledge of literary works through the use of allusions, quotations etc. then yes, Harris is likely right and yes, it was a phenomena largely confined to the ancient elites of the Mediterranean world. But if we are talking about functional literacy or one step up the ladder commercial literacy or even ordinary school boy literacy, then we have a much broader group of people involved.

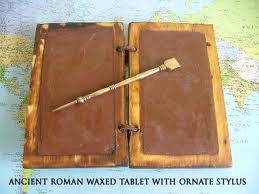

By functional literacy I mean simply the ability to read necessary data because one knows the alphabet and can decipher words— names in a list, sums on a tax bill, political advertisements on a wall, census documents, simple personal letters or remarks on media ranging from a papyrus to a potsherd. This is nowhere close to literary literacy but many people had such abilities in the Greco-Roman world. And many more could actually also compose such documents, for example tax collectors and businessmen.

One of the more remarkable finds discussed in Johnson’s book is the collection of documents on lead from about 500 B.C. that reflect business correspondence not between elite members of society or politicians, but between ordinary business men like the famous Flavius Xeuxsis whose tomb stands in Hierapolis on which is the boast of his some 40 plus safe voyages to Rome and back on business. A certain level of literacy was required in the ancient world to do business of various kinds, not least in the growing book trade in the first century A.D. And here is where I speak about the Random Reader.

Various kinds of communications in antiquity were not targeting a specific audience, much less an elite one. I am referring to the famous graffiti all over Pompeii, ranging from political slogans to prostitution offers, to quotes from Virgil’s Aeneid, and much more. But we also have such graffiti in other cities in the Empire, for example the now famous graffiti, including Christian graffiti from Smyrna. This sort of evidence makes clear that it was assumed that a wide swath of the population could at least read.

Sailors getting off the boat in Pompeii or Naples or Herculaneum looked for the advertisements for ‘love for sale’. They were hardly elite members of society. But consider as well all the huge number of epitaphs on tombs, inscriptions and political propaganda on buildings, warnings on temples (see the famous Theodotus inscription on the Jerusalem temple). All of these presuppose surely a large number, if not a majority of the people seeing such non-targeted communications could read them! The evidence of a huge amount of writing for random readers, not elite communities, must be taken into account when we do literacy estimates. I am not suggesting that this somehow proves that the ancient world was not largely composed of oral cultures or that ancient texts were not by and large oral ones. They were.

There is a further interesting piece in the Johnson volume about how public communications meant to be read silently had separation of words, whereas scriptum continuum was for things that were meant to be read out loud, whether in a document or on a stele (see the book by P. Saenger Space Between Words, 1997). It is scriptum continuum that dominates the landscape of antiquity when it comes to written documents that are not lists of some kind. We will say more about all this in our next post.