How did scribes copy manuscripts? Did they take dictation, or copy line by line? Was there a particular professional way to form the Greek letters? In our last post here, we will allow William Johnson to offer us his findings on these sorts of matters.

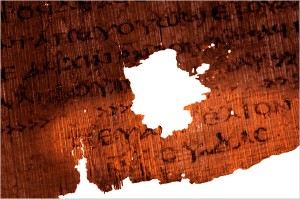

p. 4— Johnson says “Systematic analysis of hundreds of bookrolls shows…that the rakish lean often seen in the columns of an ancient bookroll is a deliberate design feature…” Note the use of scribal dots to mark out the pattern before the column was written out. The bookroll was designed accordingly to principles surprisingly different from those of the codex.

pp. 8-9— “Obviously deliberate are the limited number of script types, and the consistent look and feel, such as the wide margins or (for prose) the narrow columns and very narrow intercolumns. Less obvious, but perhaps more telling, are subtle features such as the frequent slant to the columns and the tight spacing between the lines….the overall look of a document and that of a literary roll could not be more different. “

He remarks on “this definiteness and constancy of form. The tradition of book production is fundamentally conservative in almost all times and places, and it is reasonable to suspect from the outset that even subtle changes to the look of the bookroll may be the result of definable shifts in time or circumstance.”

p. 10– Too much of the study of papyri rolls has been based on too little a sample size. For example Fredric Kenyon puts the roll length limit at slight over 10 meters…. But this is based on exactly 14 rolls, and Johnson says… it turns out he is wrong.

p. 32— Of the sample size investigated, over half the papyri have either scholastic comments or sigla in the margins, and even those that don’t often enough have variants in the margin. In the sample, standard school texts such as Homer do not predominate. Rather these are mostly texts custom made for serious readers. “In none of the texts is it clear that the annotator has the same hand as the scribe who copied the text.

p. 33 In regard to format, the identity of the scribe is sometimes confirmed or rejected on the basis of layout. “Many of the formats are…strikingly homogeneous. Wherever it is possible to compare column width of different prose texts, the width agrees either exactly…or very nearly….in a well-executed literary roll, column widths seems to be measured before the writing of the column.(Moreover the scribe seems to have measured the columns one by one as he went along…).” Because column width remains constant indeed often exact, whereas the size and spacing of the writing can vary enormously this strongly suggests the columns were measured first before writing.

p. 34— The evidence Johnson examined disputes the common assumption that oratory tended to have narrow columns, commentaries wider columns, with history and philosophy in between. In other words, format is not apparently dictated by genre of the work copied.

p. 35 There were clearly various grades of papyri, from low to high quality. A given scribe may well use different punctuation systems for different texts, and rule of thumb in the Roman period seems to be that if a scribe found punctuation in the original, he was expected to copy it into the copy. Scribes tended to ignore reader’s scholia in the margins. Copying line by line is known, but it does not seem to have been customary in Oxyrhynchus in this period. He concludes this because line length doesn’t seem to vary, even when letters or added or accidentally omitted.

p. 53—There is good prima facie evidence that the near uniform evidence of column width in the Roman period suggests a tool of measurement to control the layout of the text, and this seems to have been part of the standard training of scribes.

p. 58— The evidence from scribal error argues mainly against the notion that scribes mostly copied line by line. Elaboration of punctuation over time is not in evidence…it does not appear that scribes did more than copy what punctuation they found in the original. But a scribe would make additions or corrections as he saw fit. Reader’s marks or scholia were largely ignored.

Now all of this is relevant to the study of early Christian manuscripts. For example, if Christian scribes were like the scribes at Oxyrhynchus then it is unlikely they simply copied into NT manuscripts the comments of previous scribes or readers found in the margins. At the same time, it is possible they might have left notes about variant readings in the margin. It needs to be noted however that scribes could do erasures or mark throughs, though it was difficult and sometimes messy. It depended on who the copy was for (e.g. was it for a patron or for personal use).