Much of southern Italy qualify as being in a semi-tropical climate. Thus plants like the bougainvillea seen above from Pompey can grow all year round without fear of frost. It is not an accident then that the ‘beach resorts’ of the rich and famous in ancient Roma were also in the southern part of Italia– in places like Pompey, and Herculaneum (or as it is called today Ercolano). The Italians have a word for ruins–scavi, and thus those who pick over or regularly wander through ruins are ‘scavengers’. So it was that Yuliya and I made the necessary train trip to Napoli (in the shadow of Vesuvio), and then by taxi to Pompey itself.

May I urge you to read Robert Harris’ fantastic novel about the eruption of Vesuvius and what it did to Pompeii— simply called Pompeii? It gives you a real sense of what happened during those tragic days in the late 70s A.D. Some Jews thought that the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum was God’s reprisal for the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in A.D. 70. If so, God certainly waited awhile to respond.

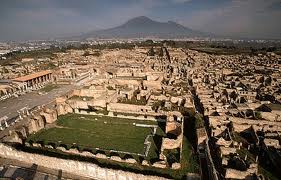

Let’s be honest, you can’t do justice to Pompeii in even a full day tour. I mean just look at this picture below….

There is a veritable ocean of ruins at Pompeii, and though I have gone various times to the site, I still haven’t taken it all in. These days, due to governmental cut backs in funds for restoration and maintenance, important parts of Pompeii are closed to tourists, including for example the famous house of the wine merchants. Repair work has stopped, never mind digging. Italy is almost as broke as some other European countries, and of course the first cutbacks are always of things like national parks, or things having to do with the humanities. It is always thus.

When you think of Pompeii and Herculaneum you need to realize they had two rather different fates– Pompeii suffered from gas, ash, and lapilli (little molten volcanic rocks that set things on fire).Herculaneum was buried by molten mud and lava. You can see this from the ash encased remains of humans stored in the lock ups at the Forum site in Pompeii—

And animals choking from the gas and ash, struggling for breath…

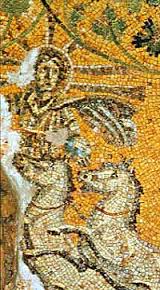

Yuliya and I concentrated on the major houses that can still be visited, like the house of the Tragic Poet or the House of Claudius Polybius (no not the famous Claudius or the famous Polybius). What you see in some cases is the remains of spectacular mosaics or frescoes–

This scene should look familiar. It’s Alexander winning the battle of Carcarmesh over the Persians. The Romans, especially the Roman military who mustered out, liked mosaics and frescoes like this. Obviously, Augustus and his followers were trying to emulate the great builder of Empire before their time who was also from ‘Europe’ (to speak anachronistically)— Alexander. In general the Romans loved all things Greek when it came to culture, religion etc.

There is an award-winning CG video made in the 90s which the British Museum still sells (in conjunction with their recent exhibit on Pompeii and Herculaneum) which gives you a lively sense of the before and after of the eruption of Vesuvius.

There is an award-winning CG video made in the 90s which the British Museum still sells (in conjunction with their recent exhibit on Pompeii and Herculaneum) which gives you a lively sense of the before and after of the eruption of Vesuvius.

What the Romans added to the Greek cultural mix was technology, engineering, military skill, administrative abilities, and persistence. If you want a broad generalization the Greeks were largely right-brained, the Romans left-brained, the former good at the arts, the latter good at science and technology. Take for instances the streets in Pompeii– obviously you needed stepping stones to get past the ordure in the street— feces, vegetable matter, refuse in general…

The disparity between rich and poor was much more drastic in Roman times than in modern America, with about 2% of the population controlling 98% of the wealth, not to mention owning various other human beings. In a wealthy town like Pompeii there were undoubtedly many slaves. But the poor leave few remains, and so much of what you see in Pompeii scavi is the remains of wealthy homes, shops, official buildings, forums, stadiums. The poor, now as then, are largely invisible, though the graffiti at Pompeii sometimes gives us clues (see the previous posts I have done on Graffiti in the Greco-Roman world).