A masterpiece of tension and atmosphere, “The Witch” left me disturbed and unsettled; it’s not hyperbole to suggest that it rattled my soul. Not merely scary, it’s the rare horror movie that is legitimately horrifying.

Whether that’s a compliment or a caution, I’m not sure. It’s probably both.

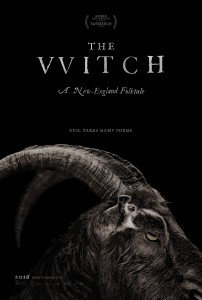

Billed as a “New England folktale,” Robert Eggers’ directorial debut tells the story of a Puritan family cast out of their community after the father, William (Ralph Ineson), confronts the town elders for their flawed doctrine. William and his wife, Katherine (Kate Dickie), move the family to the wilderness to make a life with their children: Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), two young twins and an infant. When the baby goes missing under Thomasin’s watch, it’s just the beginning of the family’s woes. Crops die. The family’s goat, Black Phillip, becomes unruly. Consumed by sorrow, guilt, fear and superstition, paranoia strikes as the family begins to fear that there’s a supernatural reason to their misfortune.

Following in the footsteps of “The Babadook” and “It Follows,” “The Witch” marries terror with art house technique. It isn’t a shlocky gore-fest filled with jump scares and a cast of nubile teens. Rather, it’s a dread-soaked, gorgeously photographed slow burn that takes its cues almost verbatim from Puritan folklore. I imagine that many who don’t bolt for the doors when they discover the fate of the baby (no spoiler; it happens in the first 10 minutes) will do so when they’re subjected to 17th century dialogue for more than 15 minutes.

I can’t recall the last directorial debut that was this confident and skillfully made. Eggers lets despair and anxiety trickle in bit by bit, filming in low light and bathing even daylight scenes in a pale, foggy grey. It looks almost like a grim oil painting. The forest stands just at the edge of the family’s homestead, foreboding and dark, as Mark Korven’s droning, plaintive score burrows under the skin. The tension slowly ratchets up through little moments. A rabbit on a path. The creepy nursery rhyme the twins sing as they play with the goat. Caleb’s questions about the hell fire and damnation he’s afraid await him if he doesn’t properly confess every sin. Even the Jacobean dialogue, with its florid sentence structure, thees and thous, and constant pleas for expiation and salvation, is just “off” enough to keep the film off-kilter. Emerson’s mastery of tone is unhinging, even when very little happens; for much of the first hour, we’re watching a family drama tinged with religious paranoia and fear, with the only hint of any supernatural threat the rare glimpses of a naked old woman doing something foreboding in the woods.

It’s no easy feat to look natural while spouting Puritan verse, and the cast is key to making this more than just an effective technical exercise. Taylor-Joy, in particular, is quite a find, with only a few credits to her name. Thomasin’s burgeoning womanhood threatens her family, and her curiosity is not approved of at a time when kids were supposed to just do their chores and say their prayers. Whether Thomasin is secretly involved with supernatural trickery or simply the target of an attack is not revealed until the film’s end, and the young actress does a fine job as the film’s unreliable entry point. Likewise, Ineson is fantastic as the family’s patriarch, with his deep voice and severe looks perfectly capturing the image of a stern Puritan father. Yet, there’s a kindness and softness to William that’s refreshing and gives the film just enough breathing room to keep it from being too claustrophobic. Dickey largely just plays notes of mourning, but they’re incredibly effective. And Scrimshaw is quite great as Caleb, nursing guilt over the furtive glances he steals at his sister and wondering if unconfessed sin will damn him to hell. He’s also responsible for one of the film’s most terrifying moments, in which an urgent, hysterical prayer chills the bones.

The film slowly turns the screws and sets up the family’s dilemma before unleashing a torrent of hysteria in its final half hour. Eggers goes all in, taking the film to areas that could be laughable in a lesser filmmaker’s hands. But his skill matches his confidence, and the film builds to one horrific crescendo after another, going beyond simple scares to a point where I felt genuinely disturbed by what I was watching. Its final moments are a fever dream of violence, nightmarish imagery and mysticism, and its closing shot of a tear-and-blood-soaked face, laughing and crying, has haunted me since I first saw the film a week ago. “The Witch” opens with the feeling that something isn’t right; its closing moments suggest an entire world gone wrong.

From a technical standpoint, “The Witch” is superb. I have no doubt that Eggers is going to do great things. I can’t deny the artistry on display. Whether I can recommend “The Witch,” however, is another matter. And to tackle that, I have to delve into some spoilers regarding the film’s ending.

SPOILERS FROM HERE OUT

“The Witch” has garnered some controversy over its recent endorsement by The Satanic Temple. While an admittedly brilliant marketing tactic, I think the film is complex enough to deserve more than simply serving as a lightning rod. In many ways, this is a story about the effects of faith without grace. Several times, members of the family voice their fears about going to hell if they die over unconfessed sin, and there’s a quiet sense of unease about William, who was so sure of his reasons for leaving the community; could he have been wrong? The family prays constantly and their conversations are full of theological discussion; they believe they are sinners desperately in need of God’s forgiveness, and yet they talk more of sin than grace. There’s a works-based, damnation-obsessed religion at play here, and the film posits that a faith that is obsessed only with how terrible we are will ultimately result in death and disaster. (A quick aside: As someone who has read the sermons of Jonathan Edwards and often reads from ‘The Valley of Vision,” a book of Puritan prayers, I’m a bit tired of the misconception of all Puritans as lacking joy and grace. I understand certain sects were that way, but I wish we could move to a more nuanced look at the time).

It’s also worth nothing that, according to a disclaimer at the end of the film, Eggers based his scripts around actual Puritan folk tales and transcripts from court cases at the time. The film takes the beliefs of that time seriously, not dismissing them as paranoia and superstition but treating this as a true “Puritan nightmare,” as Eggers has called it elsewhere. This is a film that asks what the result of obsessing over sin and hell gets us; in the end, it gets us death and destruction, and pushes our children to run from this religion’s stringent grasp. It’s also a film that looks at repression, legalism and sexism, although I’ll stop short of calling it a tale of empowerment, as some have, given that its empowerment and “freedom” comes with a price tag of death and blood. Those are themes worthy of exploration, and the film’s final moments leave no question that the end result of its characters actions is a world of horror and disorder; we’re meant to leave chilled and haunted.

So no, I don’t think “The Witch” is a movie with evil intent. It is meant to show us the horrifying implications of the culture these characters inhabit, and in doing so it’s just as effective as “The Exorcist” or “The Crucible,” two films it has many similarities with. The fact that I left stunned and shaking means Eggers did his job right.

However, there’s probably wisdom in a “pump the brakes” approach to this film for many. In the end, “The Witch” is a movie that treats the presence of the supernatural seriously. There is an evil manifestation in the woods that takes lives and bewitches children, allows a faithful family to come unhinged, and ultimately seduces one over to its side. And God? In this film, he’s aloof or nonexistent, either impotent or indifferent. And while I understand that that’s a true nightmare and a horrifying thought, it’s not one I necessary care to spend too much time with. It’s a worldview I don’t subscribe to, and it left me feeling drained, upset and depressed. That’s a mission accomplished for Eggers, to be sure, and I don’t want to slight his artistic achievements. But while I appreciate “The Witch’s” creative merits and its serious approach to horror, its hopeless conclusion is antithetical to my worldview. Its discussion ends up feeling one-sided, and its horrific images culminate not with hope but with confirmation that the world is just as wicked as its characters suspect. I don’t mind truly scary movies (“The Conjuring” and “The Babadook” both my my top 10 lists the years of their release), and I don’t think happy endings are always necessary. But my faith tells me that good wins out in the end, and I find myself wired to reject films that end without a sliver of hope, no matter how thematically earned they may be. I absolutely agree with those praising this film’s artistry and I’m curious to see what Eggers does next. But I have definite hesitations about recommending “The Witch” for discerning viewers, and it’s one that’s left me troubled and shaken.

Some will take that to mean that Eggers has succeeded in making his tale of horror. I suspect he has. I wish him the best in his career and look forward to seeing what else he has in store. But I doubt I’ll ever be spending time with “The Witch” again; life’s too short for another descent into darkness.