That would be sermons. A group of scholars gathered at Harvard recently for a conference on “Preaching the Saints,” which offered a fascinating glimpse into the art of preaching from the Middle Ages.

From the Harvard Gazette:

Theological and moral messages delivered centuries ago also help today’s scholars investigate the social content of the Middle Ages, including politics, trade, marriage, the lives of women, and, of course, the business of religious devotion. Some sermons, delivered to monks and nuns in Latin, were meant to encourage meditation and inward thought. Others, delivered in the vernacular, were meant to instruct sometimes unruly lay audiences about Christian teachings and to refute paganism. One ninth-century preacher exhorted his listeners to stop howling at the moon. Though commonly designed to explain Scripture and to urge moral behavior, sermons sometimes had more homely missions, like praying for rain. And a few had covertly political missions. In the name of doing penance for sins, for instance, some preachers exhorted listeners to join in crusades.

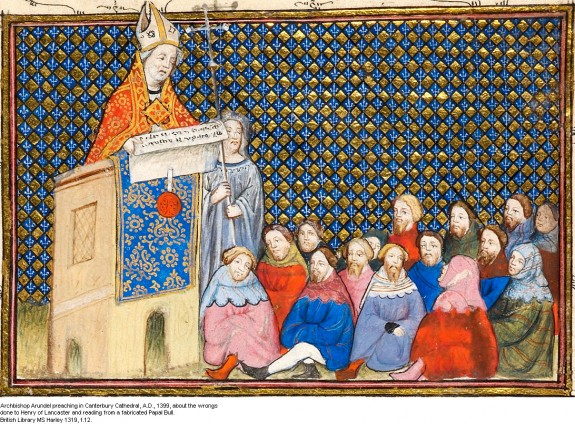

Before the printing press, knowledge was disseminated through oral traditions. In the public sphere that meant sermons. These discourses from the pulpit were the Internet and the mainstream press and the propaganda machine of the Middle Ages. At the same time, sermons of nearly a millennium ago prompted a very modern question: Who has the right to speak? Vying with priests for the right to preach were lay people, lawyers, kings, and public officials. In a bit of recurrent culture shock, even women demanded the right to preach sermons.

Most of all, the prospect of lay preaching “was an anxiety for the Church,” wrote Carolyn Muessig in a study of medieval preaching and society. (The University of Bristol scholar delivered the first paper at the Harvard conference.) The concern, she wrote, was the Vatican’s desire to protect people from heresy and “to preserve a clerical monopoly on learning.” The debate over who owned the medieval airwaves went on for hundreds of years. As late as the 14th century, one critic still held that the Vatican had the final say. “No lay person can preach without authorization,” wrote Robert de Basevorn, “and no woman ever.” There were exceptions to the gender rule. Most famous was poet, visionary, herbalist, and polymath Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th-century Benedictine nun. Muessig co-edited a 2007 edition of her homilies—sermons—on the Gospels, “Expositiones evangeliorum,” with Harvard’s Kienzle.