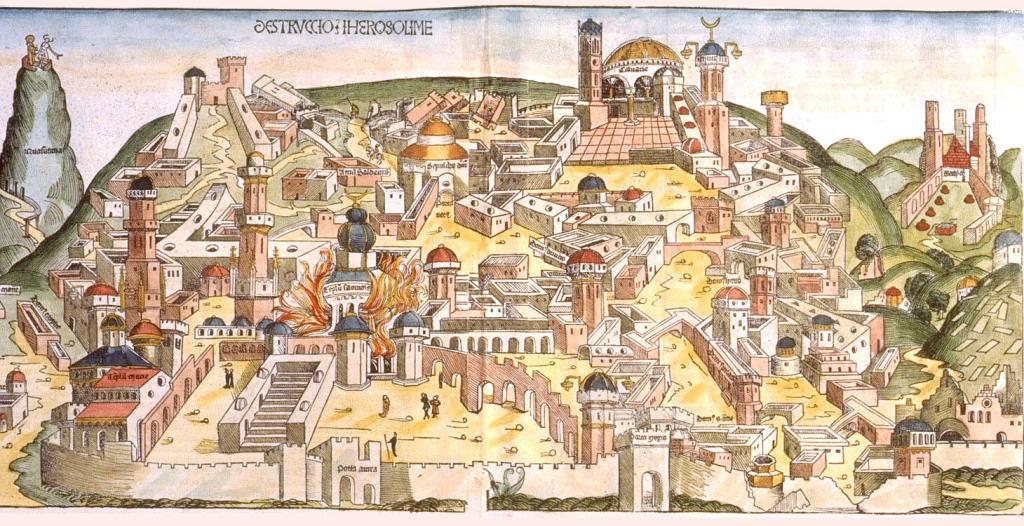

This is the final post in a series on the importance of narratives—and of urban narratives specifically—in shaping how we think about technology. After considering narratives of Babel and New Jerusalem, I will next consider one about Jerusalem during the first century of our era. Unlike the primordial city of Babel or the apocalyptic city of New Jerusalem, this is a historical narrative about a city situated between the fall and fulfillment of human technological innovation.

Jerusalem figures prominently in the biblical narrative. In the Hebrew Bible, it is the political and spiritual center of the world—the city David established for his throne and in which Solomon built the first temple for the God of Israel. Even after the city’s fall to the Babylonians and its modest rebuilding under Persian rulers, Jerusalem remained the focus of hope for a better future.

By the time the books of the New Testament were written, Jerusalem had also come under the control of Hellenistic and Roman rulers. It fell again under the latter, who destroyed most of the city during the Jewish-Roman wars of the first and second centuries. Before these wars, various forms of Judaism were present in Jerusalem: Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, Zealots, and others including followers of Jesus. All of these groups, interacting with each other and their Greco-Roman context in different ways, made Jerusalem a volatile center for competing narratives about the future of the city and the world.

The Reformed sociologist Jacques Ellul claimed that the city “embodies humanity organized against God … a refusal of God’s gift of Eden.” What Ellul saw in the city was a technological order and mentality that sought a total control of reality, closing off greater truth and God’s grace. And yet, before Jerusalem’s fall in the first-century Jesus came to this city to introduce a new technological order.

In 1942, The writer Charles Williams, who has been called the third Inkling after C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien, wrote a radio play for the BBC called The Three Temptations. In this drama, Williams aligned the temptations of Jesus with the technological orders that dominated Jerusalem in the first century: the institutions and systems of the “palace, praetorium, and temple.”

Williams frames Jesus’s earthly ministry with “the desert and the cross.” At the beginning of his ministry, Jesus is tempted in the wilderness by the Evil One to turn stones to bread, to accept earthly power by acknowledging the power of the Evil One, and to test God by throwing himself down from the Temple. Jesus rejects the Evil One’s promised comforts of satiety, glory, and safe religion and reminds the Evil One that one “does not live by bread alone,” that God alone should be worshiped, and that God should not be tempted.

The Evil One then promises Jesus that his rejection of earthly pleasure, power, and salvation will be absolute: Jesus will suffer in the flesh, his followers will betray him, and he will be separated from God. These promises are fulfilled through the work of the three lords who orchestrate Jesus’s crucifixion: the local ruler Herod, the Roman ruler Pilot, and the religious ruler Caiaphas. These three, aided by Judas Iscariot—who is called Everyman, and settles for some silver and the comforts of a house in Galilee, a Roman title, and a place at Temple services—act to protect the accomplishments and comforts of material wealth, political power, and established religion.

But as the play ends, the death of Jesus begins to negate these technological orders and inaugurate a new one. The various narratives of desire, hope, the sacred, alienation, and exploitation encounter a new creation, which includes the City of the Apocalypse that Williams said was “almost” described in the last paragraph of the Apostles Creed.

As Craig Detweiler highlights in iGods, Jesus himself was a part of the technological order. He was a τέκτων, which means carpenter or builder, and he was a teacher who made “more references to construction and finance than agricultural allusions.” When Jesus began his ministry, people who knew him said, “isn’t this the tekton?” or “the son of the tekton?” Initially, this was surely meant as a critique: why was a technologist speaking like a theologian? Later, his followers understood him to be the Maker and the Son the Maker.

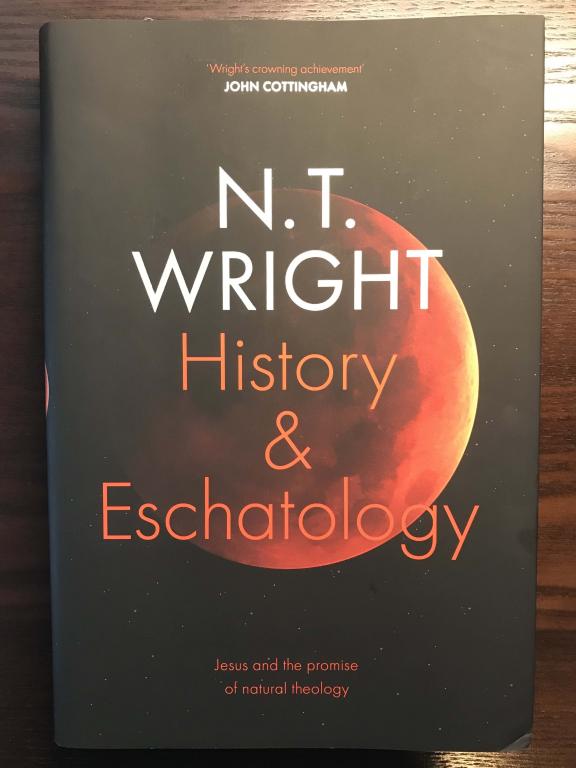

Hugh of St. Victor spoke of three books or sources of creation. One book includes God’s initial creative work and the work of nature, “in which visible work is written visibly the invisible wisdom of the Creator.” A second is the book of human work, of what humanity “makes out of something.” Because human work is corruptible, it deforms the world formed by God. The third book is the reformation of creation—the new creative work of Jesus Christ, mediated through his embodied life in the first century, the testimonies of his followers written in the following decades, and the sacraments of his church practiced throughout the centuries since.

The third book transforms human work and the technological narratives of suspicion—of Desire, Hope, the Sacred, Alienation, and Exploitation—and it replaces the ancient image of Babel with the future image of New Jerusalem. Thus Hugh, twelve centuries into the Christian era, was able to praise the creative and redemptive powers of technology.

We may see more of Babel in our increasingly technological cities, but there is more to see. C. S. Lewis said that for many the “prevailing impression made by the London streets is one of chaos.” But Williams, he said, saw something more: a pattern of exchange that was an “imperfect, pathetic, heroic, and majestic image” of New Jerusalem.

There is more present in our flawed cities than the love of self. As the theologian Philip Sheldrake says, “the human city is always a provisional reality that can … prefigure the mysterious Heavenly City.”