The last few months have clarified and revealed—in an apocalyptic way—a number of significant things about our present lives and world. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation of education and the church, and intensified ethical reflections on artificial intelligence. (I mention education because it is my profession, the church because I am directing a grant focusing on this, and AI ethics because it is a research interest.)

The impacts of COVID-19 also seem to be awakening more of us to enduring inequities in our society—racial, economic, technological, and others. For many these are not new revelations, but as one university president recently put it, “It’s like a veil has been lifted allowing us to see more clearly what was there all along”—and, she adds, “we must seize the clarity this moment offers.” Those of us in positions of power and privilege must repent of and commit to repairing these injustices.

Like many other university professors, I am revising my syllabi to emphasize systemic racial inequities. For me, this touches on the subjects of education, technology, and theology. In one of the classes I’m teaching this summer, I added an essay by Jennifer Harvey, “Shall We Awake?,” from Between the World of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Christianity. In this essay from 2018, which catalogues racial crises leading up to our present moment, Harvey brings together Coates’s diagnosis of “the Dream” and Willie Jennings’s diagnosis of “The Christian Imagination.” She calls on white Christians to awake from ignorance of racial injustice, which makes the American Dream a nightmare, and to reform our theological, moral, and political imagination.

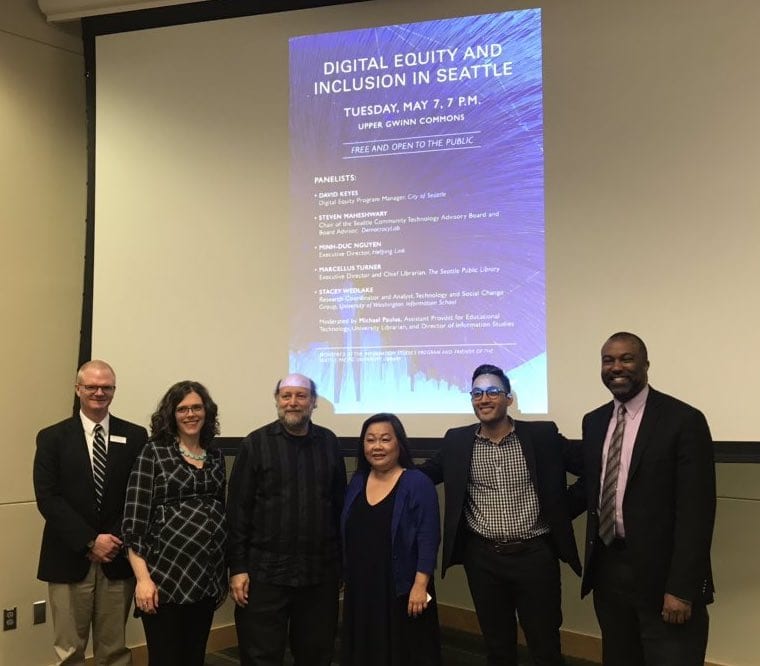

For another class I’m teaching this summer, related to the digital transformation of the church, I’ll be using resources associated with a summit I co-hosted on the topic last month. These include a panel discussion on “Digital Equity and Privilege during the Pandemic” (included in the recording available here) and a follow-up video (in development).

For a new class I’m teaching this fall called Digital Futures, I’m looking forward to including Ruha Benjamin’s Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, which explores how “new technologies reflect and reproduce existing inequities” at the same time they “are promoted and perceived as more objective or progressive than the discriminatory systems of a previous era” (3). In addition to focusing on racial bias in data and algorithms, Benjamin’s synthesis of science and technology studies and critical race studies reveals “not only that any given social order is impacted by technological development, as determinists would argue, but that social norms, ideologies, and practices are a constitutive part of technical design” (21).

The pandemic—and the related infodemic, the digital transformation it has accelerated, and the social and especially racial inequities it has highlighted—have caused me to rethink the 9.5 theses I posted on this site on the last day of 2019. I will be using these to organize my Digital Futures class.

At this point, the most significant change is a reordering of the theses. The first thesis, previously the third, is:

- We are living through a unique and transformative moment in history. New digital and networked information and communication technologies, increasingly powered by autonomous and intelligent systems, are profoundly and irrevocably changing our lives and world.

Although I’ve updated links to point to COVID-19-related posts, the thesis itself remains the same. (The key text for this will be Luciano Floridi’s “Why Information Matters.”)

And what was previously the seventh thesis is now a more expanded second thesis:

- Our present revelatory or apocalyptic moment uncovers old patterns of injustice and alerts us to how technologies create asymmetries of power that exacerbate old and create new social inequities. With digital technologies, we see these in divides relate to access, literacy, and wisdom.

What was missing in the original thesis was an acknowledgement of how “new technologies reflect and reproduce existing inequities,” which our present moment helps us see more clearly. Race after Technology (the key text for this thesis) provides an important critique of how “digital divide” framing can reproduce “culturally essentialist understandings of inequality” (22). I need to keep thinking about how digital “divides” related to access and literacy are embedded in limiting technological narratives.

Changes to the other theses are minor at this point, but I will continue to refine these. When I have a version ready for the fall, I’ll share them again here.