Within that last couple of weeks, I’ve been involved with two academic presentations and two substantial administrative discussions on the topic of digital transformation. Although I prefer the broader language of information revolutions, digital transformation (Dx) is useful for talking about our new and emerging relationship with digital technologies.

The idea of Dx is that exponential digital information and communication technologies (ICTs)—such as big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence—are fundamentally changing us, individually and collectively, as our identities and institutions engage with and are enhanced by the new digital dimension of our reality. EDUCAUSE, a nonprofit association focusing on technology in higher education, provides this definition:

Digital transformation (Dx) describes a cultural, workforce, and technological shift, enabled by advances in technology that include analytics, artificial intelligence, cloud, mobile, social networks, storage capabilities, and more. … these forces make it possible to think differently about higher education, with the potential for new business models, better student outcomes, and different, more innovative, approaches for teaching learning, and research.

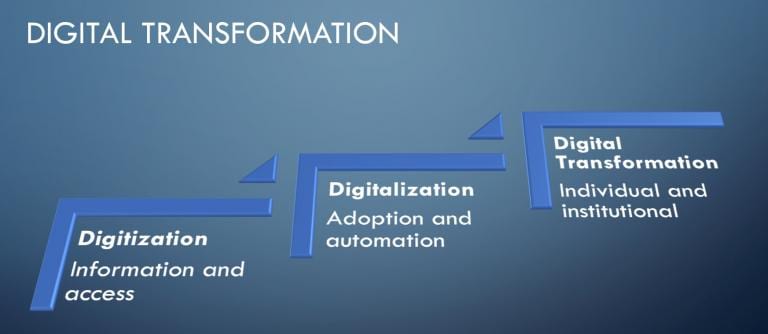

Digital technologies have been changing our lives since the middle of the twentieth century; Dx focuses on what we are experiencing now.

With the first digital computers, we began digitizing information. Then we began adopting increasingly complex digital technologies to automate work. In 1956, the term “artificial intelligence” was chosen to describe the complex information processing technologies that have come to permeate our lives. Now, we are using AI and other exponential technologies to do more work that once required human intelligence and agency—as well as entirely new work. The freedom from some forms of work and the opportunities afforded by new forms of work enable us to reimagine the work we are able to do.

In my academic and administrative presentations, I pointed to three strategies for responding to Dx (which I mentioned in my last post in connection with different theologies of technology): rejection, critical acceptance, and proactive design. Rejection, an option not entirely open to most of us, can lead to digital minimalism or even digital teetotalism. Critical acceptance, which is the default position for most of us, tolerates technology through practices of digital moderation. What Dx requires, however, is proactive design.

Designing proactively for the profound changes we’re facing, understood as part of our current information revolution, requires what we describe on this blog as digital wisdom. (Speaking of digital wisdom, the collaborative essay that led to the creation of this blog—which presents a framework for digital wisdom in higher education—was recently published in Christian Scholar’s Review.)

Digital wisdom, as it was initially conceptualized by Marc Prensky and in my broader use of the term, has a dual meaning. It involves wise use of digital technologies, which enhances our innate individual capabilities. But it also involves using digital technologies to become wiser, which makes digital wisdom teleological—i.e., concerned with broader individual and collective goals and ends. Both dimensions of enhancement are important: How might we be transformed wisely by digital technologies and to what wise ends?

Dx impacts my own work on a number of levels. First, as an academic administrator, I’m interested in the future of educational institutions—especially universities and libraries. Second, as an educator, I’m interested in how best to prepare students for life and work in the future. Third, as an academic whose teaching and scholarship focuses on new ICTs, I’m interested in understanding and engaging with the cultural transformation associated with these technologies. Finally, as person of faith, I’m interested in the theological implications of all of this.

In future posts, I’ll bring these various perspectives together to focus more on the future of education, work, and ethics.