In an earlier post, I highlighted Luciano Floridi’s argument that we are living through the fourth major revolution of the modern era—an information revolution. Looking more broadly at information and human history, and considering the human revolutions that have occurred alongside natural evolution, Floridi’s fourth revolution also can be thought of as the fourth information revolution.

The four revolutions are connected with the invention of abstract information about 100,000 years ago, of information agencies by 10,000 years ago, of information artifacts some 5,000 years ago, and of information automation within the last 100 years.

At the beginning of these information revolutions was the emergence of imaginative language—the ability to communicate more information (as well as misinformation and disinformation) about observed phenomena, others, unobserved phenomena, and imagined things. With the ability to create new information consciously, we began to use our enhanced communication skills to tell stories.

Stories form us and, consequently, our world. Whether we recognize it or not, individually and collectively we inherit and tell stories that expand or inhibit our imagination and creative abilities. The future we are creating through our current information revolution will be shaped by the narratives that have shaped us and by the narratives we shape.

In my next few posts, I will explore narratives that are both technological and theological. In this post, I will focus on the formative influence of narratives—especially for thinking about the technological opportunities and challenges before us. In the next three I will explore three tales of the city, which is one of the chief technological innovations of the second information revolution. These three narratives concern the primoridal City of Babel, the apocalyptic City of New Jerusalem, and the City of Jerusalem in the first century.

Our Formative Narratives

Yuval Noah Harari claims that as we face “unprecedented revolutions, all our old stories are crumbling and no new story has so far emerged to replace them.” In his book Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, Harari says the “basic abilities of individual humans have not changed much since the Stone Age,” but our stories have grown “from strength to strength, thereby pushing history from the Stone Age to the Silicon Age.”

Harari suggests two new narratives for our future: (1) “techno-humanism,” which looks to new technologies to create a “much superior human model,” and (2) “dataism,” which prefers “Big Data and computer algorithms” to “human knowledge and wisdom.” In spite of invoking the language of divinity, Harari’s narrative options are thoroughly materialistic.

The physicist Tom McLeish points out that explorations of the material world provide us with new narrative resources, but scientific exploration “has no teleological methodology or goals.” Theology, however, opens up our imagination to something more than natural or human creativity: it considers divine creativity and ultimate ends or goals (teloi). “Because theology observes and construes stories,” McLeish says, “it is able to discuss purposes and values—it can speak of, and ground, ‘teleology.’” Our theological narratives, McLeish concludes, can help us understand shared goals, common practices, and “shared experiences of creativity and constraints.”

To illustrate the significant role of narratives, McLeish highlights a research project conducted in Europe about ten years ago that explored public views of nanotechnology—i.e., the manipulation of organic and inorganic matter on an atomic scale. The research “unearthed underlying narratives of suspicion—stories and themes that influence and permeate [public] debate, without necessarily surfacing.” These narratives draw from both ancient and modern myths, and “create an undertow to discussion of troubled technologies that, if unrecognized, renders effective public consultation impossible.”

The research team identified five formative mythic narratives:

- “Be careful what you wish for—the narrative of Desire,” in which we are blind to unforeseen consequences of our aspirations.

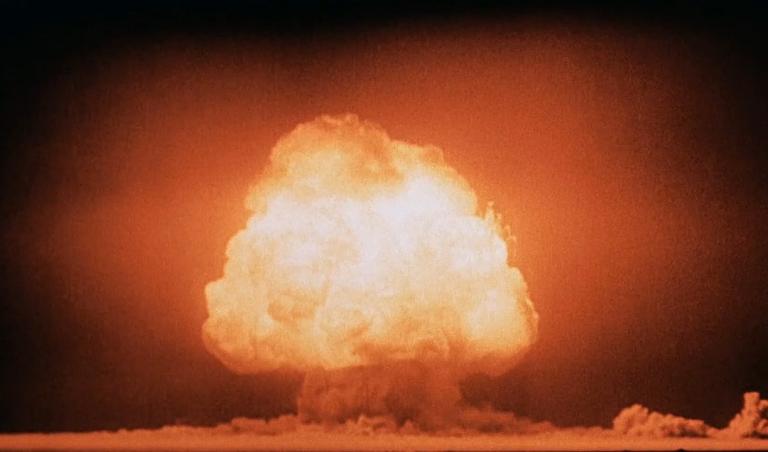

- “Pandora’s Box—the narrative of Evil and Hope,” or the fear of often irrevocable harms mixed with our ambitions.

- “Messing with Nature—the narrative of the Sacred,” which concerns trespassing on the sacred or playing god.

- “Kept in the Dark—the narrative of Alienation,” in which asymmetries of power create powerlessness, often through ignorance.

- “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer—the narrative of Exploitation.”

This analysis reveals that modern concerns have ancient roots, and that these concerns are shaped by old narratives that help us process new information. Further, McLeish concludes, this study reveals that “there is a narrative vacuum where the story of science [and technology] in human relationship with nature needs to be told.”

So how might theological narratives enhance underlying narratives, such as the five mythic narratives above, as well as explicit technological narratives such as Harari’s?

In the next three posts, I will explore technological narratives of Desire, Evil and Hope, the Sacred, Alienation, and Exploitation in the tales of three cities: Babel, New Jerusalem, and Jerusalem.