The Friends of God were committed to community. While their associations with each other were indeed informal and unregulated, they recognized the value of mutual support and encouragement in their God-friendships. The Green Isle Community is one example of this.

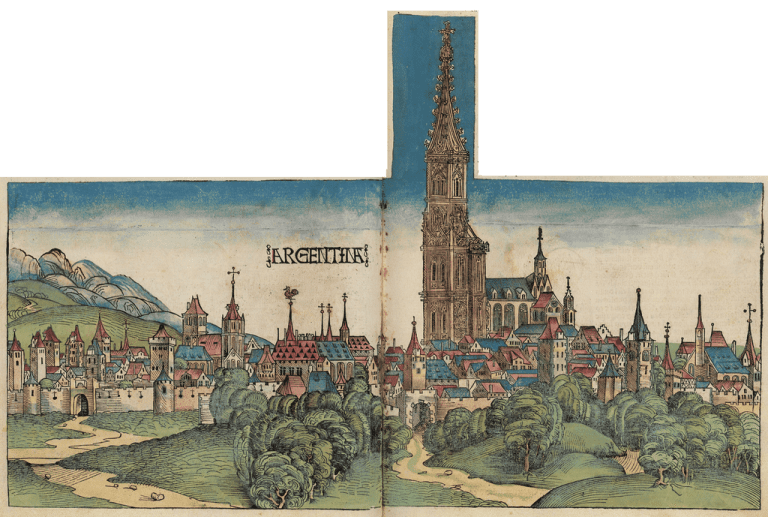

Today, Strasbourg in eastern France is known as the headquarters of the European Parliament, but it has centuries of fame behind it. Some of that fame is glorious—it was Johannes Gutenberg’s home when he created the single most influential piece of modern technology. Some of that fame is tragic, as when the bubonic plague ripped through it in 1348 killing more than 16,000 citizens. Some of that fame is shameful; the plague was blamed on Jews, and thus in 1349 Strasbourg conducted a ruthless pogrom, burning more than 1,000 Jews, expelling all the others, canceling any debts owed to them, confiscating all their property and wealth. (Anti-Semitic frenzy was always whipped up with bogus tales of conspiracy and contamination, but many times beneath it all lay the economic benefit of the seizure of moneys and belongings. The Nazis did the same thing nearly 600 years later.)

Amidst all that genius and grandeur, sickness and violence, commerce and culture, racism and greed, a man named Rulman Merswin lived and died. Born in 1307 to a family of some renown, Merswin was a successful and wealthy banker, but around 1346 the decay of the world weighed heavy on him; he and his wife, Gertrude, turned their attentions to the pursuit of the friendship of God. He purchased a small island on the River Ill that runs through Strasbourg. The island had been the site of a small convent and church two centuries before, but the buildings had been abandoned and fallen into ruins. Merswin restored the buildings and created a Foundation that could serve as a center for the spiritual pursuits of both lay people and churchmen who needed a quiet place to develop the work of prayer and meditation.

After Merswin’s wife died, he went to live on the island and spent the remaining ten years of his life deepening his own life of prayer, writing, and worshiping. After his death, his colleagues found an extensive collection of works written for and by Merswin. They include a wide range of letters, histories, testimonies, recorded conversations, teachings, histories, and memoirs.

Merswin’s writings, and those of his companions, still have value. They’re rich in 14th century spirituality, with all the markings of its age: asceticism, ecstasies, visions, voices, and other mystical phenomena. Merswin, and the other Friends of God, were convinced that God’s kingdom and the restoration of divine love in the world would come not through sword, not through coin, not through political dictate, and not through sheer human progress, but through the leavening work of the Friends—the work of prayer, worship, and listening.

While I love the mystical writings of the 14th century, and benefit from their visions and from their teachings about the love and knowledge of God, my interest in this short series of posts lies in the relationship between these Friends and their self-identification, which creates an open, but defined, community. It is this free relationship between the Friends that we seem to lack in our day. Perhaps this stems from our chronic obsessions with individualism and independence, but the network of Friends—all focused together on prayer and worship—seems enticingly foreign to me. And potentially powerful. In a non-heroic way, of course.

I think of my personal friends scattered afar—Gloria in Illinois, Amy in Colorado Springs, Darcy in Oregon, Emily in Washington, Dave in Wisconsin, Laurie in Glenwood, and so many more—and friends gathered near who are in the daily weave of my life. Part of what binds me to them is not merely our memories of friendship and occasional connections, but the knowledge that they too are seeking the mind of Christ, they too are pursuing friendship with God.

Merwin’s Green Isle Community is long gone, but it was only a temporary incarnation of an invisible society, one to which I belong. Do you?

Next up, some comments on some of the women Friends: Christina Ebner and Margaretha Ebner, Adelheid Langmann and Elsbet Stägel.

(Note: I started this series because I read Theologia Germanica, an anonymous book by a Friend of God. But I had to go further to find our friend Rulman and his story. In these posts I’m reflecting on the material found in a couple of historical studies of the Friends of God: The Flowering of Mysticism, by Rufus M. Jones, and Friends of God, by Anna Seesholtz. I already bear the weight of overdue fines at the library, so I cannot begin to pass on the extent of their work.)