David Russell Mosley

(1865/1931)

Title

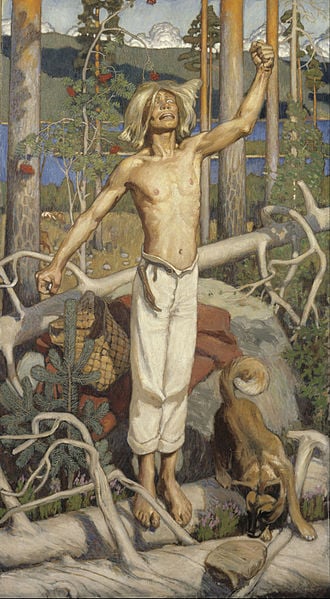

English: Kullervo Cursing

Date 1899

(Public Domain)

Ordinary Time

3 October 2016

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Readers,

Lately I’ve been encountering something that I find rather odd. Perhaps its oddness is only in that I have never thought this way myself and so being only now introduced to it, I find it strange. I’m talking about the relationship of Christianity to myth (and also to fantasy). I should note right away that I have encountered Christians who believe Christianity antithetical to myth or fantasy. There are dozens of memes, tracts, and more dedicated to this. What I had not encountered was the other side. People who loved, for instance, Tolkien, and believed that his faith would hinder him in writing fantasy; or people who enjoyed Norse myth as presented by Snorri Sturluson, but who emphasize the fact that he didn’t believe what he wrote. I’m afraid it isn’t as simple as all that.

The issue is that we like things in discreet categories. We want to put one thing in column A, another in column B and never the twain shall meet. But Christianity in particular does not work this way. Neither, for that matter does myth. In neither case are we talking about things totally discreet and separable. Allow to me to give an example of what I mean.

When Tolkien was younger, before he began school at Oxford, he encountered The Kalevala a collection of Finnish myths and stories. Since he was Tolkien, he decided to actually try his hand at re-writing one of the stories, the story of Kullervo. For those unfamiliar with the story of Kullervo it is about a young man who’s father was [apparently] killed by his uncle when he was first born, was then taken into captivity by said uncle. The uncle tried, unsuccessfully, to kill Kullervo three times, then put him to work as a slave, to disastrous effect, and sales him to a great smith. The smith gives Kullervo to his wife, who mistreats him. Kullervo causes the smith’s wife to be killed (using some magic), runs away, finds his family alive, screws up with them too, accidentally sleeps with (possibly rapes) a girl who turns out to be his sister. His sister commits suicide, Kullervo scorns his family, kills his uncle, and then asks his sword to kill him, to which it says yes, and he dies. The End. For those of you who have read The Silmarillion and/or The Children of Hurin this story should sound somewhat familiar, as Tolkien would later adapt aspects of it into the story of Turin Turambar. But before the story of Turin, Tolkien wrote a new version of the story of Kullervo, which has since been published as The Story of Kullervo edited by Verlyn Flieger.

In her notes, Flieger, along with several other Tolkien scholars, notes that it appears odd that a practicing Catholic such as Tolkien should become so enamored with such a story. You can read Henry Karlson’s post at A Little Bit of Nothing, about what these scholars said and some responses to them. For my purposes it is enough to say that some people seemed to think that Tolkien’s Christianity should have kept him from being interested in such a story, just as there are some who think a person’s Christianity can keep them from even partially “believing” (that is, taking as literal accounts of history) the various myths and legends that were preserved from destruction, by and large, by medieval monks and nuns. Yet I submit that this not odd, not for any number of reasons.

Tragedy, as an art form, is not limited to the pagans. After all, no one thinks it odd that Shakespeare wrote Hamlet (a story actually quite similar to Kullervo in many ways) and yet was also a Christian (and quite possibly Catholic). Tolkien understood what the medieval monks and nuns understood, what Christianity understands, these stories are worth preserving because they teach the truth. They don’t teach all of the truth and many of them ought not to be taken literally, that is, as historical events that happened at a particular time in the past. Nevertheless, the convey true things about the nature of humanity, the world, even God. It is not as simple as to say Christianity is true and everything else is false. In fact, as I write this, I realize that I have, in some ways, been introduced to this idea before.

C. S. Lewis, prior to his conversation, was a great lover of myth and yet believed them lies, albeit lies “breathed through silver” (a rough paraphrase of something he actually said somewhere). This is, of course, still somewhat different from the idea that a Christian, by virtue of their Christianity, ought not to be interested in myths or fantasy, but it is related since it views myths as existing entirely in the false category. Yet here, Lewis was set straight, in large part by Tolkien. In the poem, “Mythopoeia,” Tolkien addresses Lewis’s feelings that myths are lies by noting that the telling of such stories, the creation of myths, legends, elves, even gods belongs to the human race as sub-creators, in imitation of the Creator. Yes, Tolkien notes, sometimes that creation is abused as when we bow down to creatures rather than to the Creator, but that does not make the myth a lie. Rather it makes it a mistake and one once recognized that can be overcome as we read these stories in that light. Lewis eventually comes to see it this way too noting in Mere Christianity (though I can’t recall where) that in a sense Christianity gets to have all the old myths in a way that even their originators did not since we have the Truth (namely the Son, Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity). We can baptize these stories and see the way the Truth is unveiled in them since, as Tolkien writes:

The heart of man is not compound of lies,

but draws some wisdom from the only Wise,

and still recalls him. Though now long estranged,

man is not wholly lost nor wholly changed.

Disgraced he may be, yet is not dethroned,

and keeps the rags of lordship one he owned,

his world-dominion by creative act (“Mythopoeia“).

So it is not, or should not, be strange that a man like Tolkien re-wrote the story of Kullervo, that Snorri Sturluson told us about Icelandic myths, that Irish monks and nuns retained for us the myths and legends of pagan peoples. These stories are true, just not always in the way we assume they must be. A monk need not have believed that Grendel really existed in order to believe it important that we know the story of Beowulf. Sturluson need not have believed that Odin is the All-Father in order to believe that Icelandic poetry in both form and content important to remember. Christianity, rightly understood, is one of the most open religions, allowing the stories from other faiths to have voice in a way that many other religions, and certain as atheism, do not.

Sincerely,

David