Science

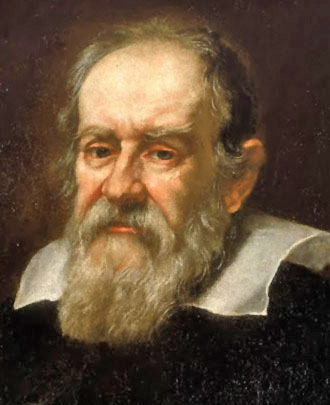

Justus Sustermans (1597–1681) Link back to Creator infobox template wikidata:Q974195

Title Portrait of Galileo Galilei

Date 1636

(Public Domain)

The last area I want to tackle briefly is the relationship of science and Christianity as presented in this article. Before I get into his presentation of Galileo, I do want to comment on a rather asinine comment Merritt makes. He writes concerning whether or not machines can have souls:

If this seems like an absurd question, consider technologies such as in vitro fertilization and genetic cloning. Intelligent life is created by humans in each case, but presumably many Christians would agree that those beings have a soul. “If you have a soul and you create a physical copy of yourself, you assume your physical copy also has a soul,” says McHargue. “But if we learn to digitally encode a human brain, then AI would be a digital version of ourselves. If you create a digital copy, does your digital copy also have a soul?”

I really can’t even begin to understand this comparison. After all, both in vitro and genetic cloning, we’re talking about doing the conception process (the combination of sperm and egg) outside of the body and then placing it back inside the body. We’re not talking about synthetic sperm or eggs. We’re not even, yet, talking about synthetic wombs. The materials are all still organic even if they’re removed from their natural processes temporarily. This is in no way analogous to attempting to digitally encode the human brain or the singularity.

Now, Merritt also assumes an antagonistic relationship between Christianity and science. He cites as examples, Galileo, Darwin, climate change and genetics. That he has history wrong here is as indisputable as is the fact that many, particularly fundamentalists and some evangelicals, think these are problems for Christianity (not so much Galileo, but the others for sure). After all, Galileo wasn’t in trouble so much for contradicting the Bible but Aristotle and the best science at the time. The math wasn’t on his side initially. Darwin wasn’t a particular problem for Christians in his own day. And one need only read the writings of Benedict XVI or, for instance, Laudato Si’ by Pope Francis to see that Christianity has no problem with believing in climate change. I’m not sure what Merritt means by “modern genetics” but given that Br. Mendel is basically the grandfather of modern genetics, it seems unlikely that genetic theory is inherently antithetical to Christianity.

So, here’s my point: I have no real fear of the rise of consciousness in robots. I’m more inclined to think the ore from which the metals of robots are made has some level of consciousness than I am inclined to believe it possible robots will naturally acquire souls/consciousness. What’s more, this article, and even, I think many scientists asking these kinds of questions, need to realize that they are doing philosophy and theology and train and study accordingly. Finally, we need to remember that Christianity and science are not at odds with one another. There is no truth science can discover that will be antithetical to Christianity, not if Christianity is in fact true. It might be the case that things science takes to be true aren’t, or aren’t true in the ways they believe them to be, but if Christians are right, science can discover nothing that will force us to completely re-think our faith. So take comfort in that.

Sincerely,

David

P.S.

Consider making a donation to this blog through the donation button on the upper right side. Many thanks to all the souls who have already done so and those who plan to do so in the future.