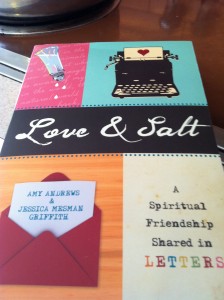

Love and Salt: A Spiritual Friendship in Letters is the kind of book that you start recommending to other people before you’ve even finished it. It will also get you thinking about your own spiritual friendships—those rare, treasured relationships with people whose company you enjoy and with whom you can discuss theological notions and the most difficult spiritual questions.

Love and Salt co-authors Amy Andrews and Jessica Mesman Griffith have this sort of friendship, in which questions about God and culture and meaning and existence and suffering and who knows what else take their place alongside more familiar friendship markers, such as visits, sharing of news, and outings with each others’ families. What makes their friendship remarkable is that they committed to regularly writing letters to one another—actual longhand letters, mailed in envelopes.

Love and Salt co-authors Amy Andrews and Jessica Mesman Griffith have this sort of friendship, in which questions about God and culture and meaning and existence and suffering and who knows what else take their place alongside more familiar friendship markers, such as visits, sharing of news, and outings with each others’ families. What makes their friendship remarkable is that they committed to regularly writing letters to one another—actual longhand letters, mailed in envelopes.

Griffith and Andrews started their letter-writing ritual during Lent 2005, when Andrews was preparing to convert to Catholicism. So from the beginning, their letters were intended as vehicles for spiritual insights and theological wrestling, not merely to keep in touch with a friend. These women are deep theological thinkers who use their regular correspondence to ponder eternal life and the fear of death, the wisdom of Teresa of Avila, how prayer works, how to eat communion wafers with reverence, and other weighty matters. They quote poetry and urge each other to read Pope Benedict’s writings (they are both Roman Catholic) with the zeal that I recommended Gone Girl to my book group. Their sharp intellects and unabashed love of theology are daunting. But two things keep their correspondence from being dry and inaccessible to readers (like me) who don’t keep piles of theology books on the nightstand.

First, Andrews’s and Griffith’s letters include plenty of references to everyday realities, from an obsession with Little House on the Prairie reruns and frequent Tolkien allusions to job complaints and annoyance with their husbands. I may not read the same kind of books they do, but their letters offer plenty of compelling glimpses into their very relatable lives as wives, employees, mothers, and laypeople.

Second, the friends delve deep into big theological questions not as some sort of intellectual exercise, but because they are trying to make sense of their own lives. They are pursuing the knowledge and love of God not because they are intrigued by the idea of God, but because their lives depend on it. Nowhere is this clearer than in Andrews’s and Griffith’s writing about how God is, or isn’t, present when we experience great pain.

About two-thirds of the way through the book, crushing tragedy hits. Nearly all of the letters from then on include some wrestling with theodicy—how God does or doesn’t intervene in human life, and what we are to make of seemingly random, crippling pain.

Jess recalls her father telling her about a dream/vision he had after Jess’s mom died of cancer in her 30s. In her father’s vision, God was a gladiator who crushed Jess’s father under his sandal and asked, “Am I sovereign?” As Jess walks through this new tragedy with Amy, she writes:

I return to my dad’s horrifying vision of God….I can’t accept it, though I know there is biblical truth in it, and the truth of tradition too….It’s the truth of Job, the crisis of faith, and while it’s good reading, there’s little comfort to be found there. But Job is not the whole story, only the beginning. Job paves the way for Christianity, for the theology of the cross: the believer must accept that death, sickness, and suffering are not punishments for sins…Suffering waits on the path of all mankind, but it’s not meaningless, for it unites us with God, who will also suffer. The God of Abraham suffers the death of his own son. Being fully human, he suffers on the cross. But we can’t know any of this until the end of the story. And it’s still so abstract. I doubt it would comfort one who is actively suffering.

As one who is actively suffering, describing in her letters animal cries of anguish and sleepless nights literally spent writhing in bed, Amy searches for answers even as she considers giving up on God entirely:

Without the feeling of God with me, I don’t know what else to do but turn to the books I have by my bed, to theology, and read and read and try to make sense of a God who apparently behaves like this, allowing innocent deaths and saints left in darkness…Lately, all the books seem to be saying the same frustrating thing: it’s a paradox. We are free, and God is in control and that is that.

Later, Amy responds to a friend’s speculation that “providence can usually be discerned only from inside a given life,” writing,

All of this—thinking of God in stories, in process, inside a given life—seems to be leading to the same point: I should stop pursuing the God of theology and turn instead to a God who lives in time with us, the God of scriptural and traditional witness.

In the end, Amy and Jess don’t figure out how prayer works or precisely where God was or is in their suffering. They don’t entirely give up on theology either. But their letters testify to how we ultimately come to know God best and make peace with God’s inexplicable presence—not by studying theology but by paying attention to our own stories and the stories of others. As I was writing this reflection, I was also reading Phyllis Tickle’s book The Great Emergence: How Christianity is Changing and Why. In arguing for the centrality of conversation and story-telling to Christianity’s post-modern iteration, Tickle writes:

Narrative circumvents logic, speaking the truth of the people who have been and of whom we are. Narrative speaks to the heart in order that the heart, so tutored, may direct and inform the mind.

In writing so beautifully, honestly, and eloquently to each other, in telling their stories as individuals and as friends on a common quest for God, Amy Andrews and Jessica Griffith speak to our hearts in order to direct our minds toward God. Theirs is not a pastel-washed, sentimental faith, however. Rather, the words they speak from their hearts, to each others’ hearts and the hearts of their readers, are trustworthy precisely because of the intellectual thirst and rigor with which they have also pursued theology, and because of their willingness to abide with the terrible knowledge that God loves us and still we suffer. The result is a unique work in which intellect and emotion are both given pride of place, both recognized as vitally important in the quest for God.

I want to shove this book into the hands of everyone with a skewed, incomplete vision of what it means to live a faithful Christian life, everyone who chops the God of the universe and the God of the cross into manageable bits with too much sentiment or too much theology or too much flat reason unleavened with story, everyone who dares believe they have God or God’s absence all figured out.

Here, you evangelicals who have the nerve to ask whether Catholics are “real” Christians. Here, you atheists who dismiss believers as blithe naïfs incapable of pondering the world’s contradictions and agony as you do. Here, you “spiritual but not religious” folk who see ancient rituals and requirements of organized religion as nothing more than superficial performance. Here, you theologians with your jargon and dry seven-point lists that cannot possibly speak to someone awake at 3 a.m., weeping and twisting in her bedsheets. Here is a testimony to what the life of faith is really like. It is messy. It is lovely. It is heartbreaking. It is joyful. It is paradox. It is true.