In the introduction to her recent book Political Tribes, Amy Chua wrote,

Humans are tribal. We need to belong to groups. We crave bonds and attachments, which is why we love clubs, teams, fraternities, family… But the tribal instinct is not just an instinct to belong. It is also an instinct to exclude.

Lately, as people wrestle with what it means to be, and to not be, an evangelical, it seems we’re approaching evangelicalism as if it is a ‘tribe.’ We want borders where borders don’t exist. Evangelicalism encompasses everyone from Jonathan Merritt to Jerry Falwell Jr., Max Lucado to Mark Driscoll, and John Piper to John Hagee. Depending on where you are in evangelicalism, there is probably at least one person in each of those pairings you’d like to exclude. Chua is right, humans are tribal, but we’re wrong, evangelicalism isn’t a tribe. So what is it?

To understand contemporary evangelicalism, we have to go back to its roots; we have to start with fundamentalism.

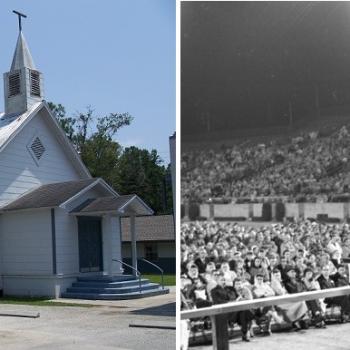

At the turn of the 20th century, the growing popularity of Darwin’s theory of evolution and the burgeoning confidence in the ability of science to answer all of humanity’s questions and problems was affecting large portions of American Christianity. A diverse group of Christians stood together to affirm truths many Christians, churches, seminaries, and denominations were abandoning–truths they believed are the fundamental to Christianity. In 1910, this diverse group of believers published a twelve-volume set of essays defining and affirming doctrines such as the reality of miracles, the Virgin Birth of Jesus, the special creation of humanity, Jesus’ physical resurrection from the dead, his future, bodily return to the earth, and so on. Their expansive work was titled The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth and soon, those who published it and those who agreed with it were called “Fundamentalists.” The Fundamentalists included Baptists, Presbyterians, Wesleyans, Brethren and Episcopalians; a group with obviously very different doctrinal positions. They didn’t whitewash their theological or practical differences, instead they focused on their agreements. It was their differences and their commonalities that helped them identify the fundamentals of the faith.

By the 1940s, Fundamentalists had, by and large, segregated themselves from contemporary culture and established their own schools, published their own books, eschewed politics, the press, and Hollywood. This happened partly because theological liberals excluded them but also because of what were, most likely, the Fundamentalists’ own best intentions: a desire for holiness in the face of compromise and a commitment to the need for personal faith in Jesus for salvation as opposed to a social gospel which promised only an earthly “salvation.”

Around mid-century, Billy Graham, Carl F. H. Henry, Harold Ockenga, and others who embraced the doctrine of the Fundamentalists came to believe that Christians were called to engage the culture with the gospel. These men and the movement they started were called neo-evangelicals.

Two seemingly-contradictory things emerge from this brief history: first, there was a unified doctrinal core to evangelicalism and second, no creed or confession was ever written to define the movement. That means evangelical theology does not derive from the label “evangelicalism.” Rather, individuals and theologians and churches and denominations who are evangelical bring their theology with them. Creeds, confessions, and statements of faith from evangelical churches and denominations often disagree on things such as the timing of Jesus’ return, sacraments versus ordinances, church polity, human freedom and divine sovereignty, etc. But within evangelicalism there is (or should be) agreement on the fundamentals: Jesus’ resurrection, the need for personal faith in him, the authority and accuracy of the Bible, and Jesus’ commission to the church to make disciples. The more refined details of those core beliefs are left up to those who constitute evangelicalism.

Having said that, English is a living language and therefore word meanings often change over time (I know! It literally makes my head explode too!) It can be frustratingly difficult to understand what we mean by “evangelical” because it may change from generation to generation. This challenge has been around for a while. One of the links on the home page of the National Association of Evangelicals is “What is an Evangelical?” Their answer:

Evangelicals are a vibrant and diverse group, including believers found in many churches, denominations and nations. Our community brings together Reformed, Holiness, Anabaptist, Pentecostal, Charismatic and other traditions…our core theological convictions provide unity in the midst of our diversity.

This difficulty in pinning down the term “evangelical” is not a bug. It is actually a design feature of the movement. Chua, a little later in her introduction says, “The tribal instinct is about identification…” so the desire to tribalize evangelicalism is understandable. But if we define evangelicalism as a tribe, we’re assuming a unified whole rather than a diversity. Therefore, evangelicalism is not a tribe and it never was. If we must identify “tribes” in conjunction with evangelicalism, it seems that title belongs to the evangelical denominations and their statements of faith. It would be better to think of evangelicalism as a common ground where these friendly tribes meet.

In the end we have to realize that evangelicalism is not a well-defined and ordered group that it can be identified, polled and surveyed. Since there are no boundaries, only commitments, no one person can truly speak for the movement. But the strength of the movement is also its weakness. Since no one is in charge, vocal minorities may be thought of as speaking for the movement when they really can’t. The problem today is that no one seems to understand that, including evangelicals.

Timothy J. Etherington is the pastor of Trinity Community Church in Lancaster, CA. He has an M.Div. from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and is married to Lisa, his perfect partner in ministry and the love of his life. They have three successful, adult children and Linus, a golden retriever who is a Very Good Boy. Tim brews his own beer and never listens to his own sermon audio.