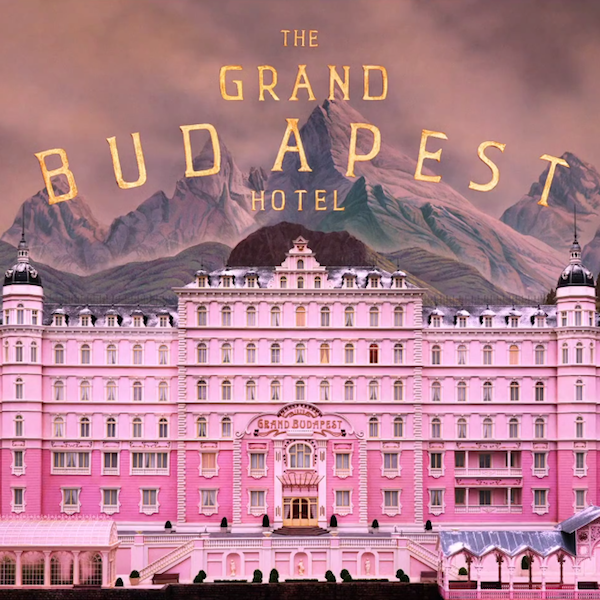

“The Grand Budapest Hotel” begins with a telescoping narrative device: a young girl—a poor, but kind man’s Lena Dunham—walks through a cemetery to pay tribute to the memory of an author who is buried there. She is dressed in a pink Girl Scout uniform of sorts and carrying a copy of a book entitled The Grand Budapest Hotel which has a stencil drawing of the hotel façade on the cover, also in pink. Think about the color pink. Think of all the words it evokes: girlish, pretty, innocent, naïve, sweet, sensual, sumptuous, decadent. All of those concepts are at play throughout the film—frequently and poignantly at odds with an ever-encroaching grayer world.

We then meet our first omniscient narrator, the author himself, who introduces his book and sets up the story of how he met the wealthy and eccentric Mr. Mustapha—or Zero, as the audience comes to know him—while staying at the Grand Budapest in the late 1960s. The real story is the one Mr. Mustapha tells the young writer over dinner, about how he came to own the once sublime and now shabby hotel. (Or maybe the idea of a real story, with clear development and tidy resolution, is just an illusion.)

Think about purple; we associate it with royalty because for centuries the pigment was so rare and costly to obtain that only the very wealthy could afford it. Enter, the captivating M. Gustave: the perfectly coiffed, generously perfumed concierge who wears vivid violet tailcoat tuxedo to work every day. He is gentle, handsome, sincere, and accommodating; yes, he accommodates famously, and he has a string of rich elderly lady friends to prove it. Peel away what Anderson’s critics call “twee” and what we have here is a well-groomed, highly organized and efficacious gigolo. That is the other side of purple: its rarity gives it value, but since it is so uncommon in nature it can sometimes have the effect of being phony and artificial, maybe even aberrant or perverted. Opinion on M. Gustave divides along these same lines throughout the course of the film.

Myself, I think he is magnificent.

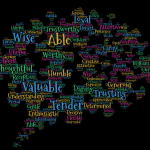

M. Gustave has a vocation to serve, and he takes it seriously; moreover, he is exceptionally good at serving, because he recognizes that while human caprices are myriad and diverse, at the root of all is the constant and immediate desire to be loved. “Rudeness,” he explains to his hotel staff during a daily dinnertime lecture, “is merely the expression of fear. People fear they won’t get what they want. The most dreadful and unattractive person only needs to be loved, and they will open up like a flower.”

But as beautifully and persuasively M. Gustave communicates his ideals, what is more magnificent is how he lives every moment with zany intensity, always driving, always seeking. He does not always display the salvific kindness that forms the foundation of his moral philosophy, and even when he puts his ideals into practice they do not always save him. M. Gustave is actually a deeply flawed person, but he does not seem to fear even his own inadequacy; he courageously confronts reality, and reality always moves him. It is not a coincidence that throughout the film the man is almost never still or quiet. At one point, after he escapes from wrongful incarceration, M. Gustave meets Zero on the other side only to find the lobby boy woefully unprepared to continue the caper. He then goes on a cruel and fairly racist tirade against the young man, who gently but firmly defends himself; within a number of seconds M. Gustave apologizes tearfully and confesses how much he loves and values his young apprentice, who graciously forgives him. M. Gustave wants to be a good man, but he knows he is not always; his shortcomings do not paralyze him—like everything else, they propel him onward.

In following his example, many of the characters in the film, particularly other members of the hotel staff, approach their lives with remarkable zeal. In one scene Zero and M. Gustave walk hurriedly passed a couple of women scrubbing a floor and I felt a pang of genuine jealousy because I do hardly anything with as much fervor and purpose as those women scrubbed that floor. Wes Anderson believes in, and ingeniously depicts, the capacity for glory in everyday existence; at the same time, however, he allows his protagonists to perform some ludicrous, death-defying feats—leaping between peaked roofs, walking between cable cars while hanging over a dizzying height, sledding down a mountain and nearly off a cliff—with ease and perfect composure. Here one must remember this is a retelling of a retelling of a retelling: the story becomes a legend, and as such the memory of fear vanishes and only the heroism remains.

Now, let us focus for a moment on this ever-encroaching grayer world: Nazi Germany, though never named, is ubiquitous in Grand Budapest. Wes Anderson has caught considerable flack for what looks like an attempt to sugarcoat the expansion of Hitler’s empire. In light of this issue, casting for the film was rather genius: along with Anderson’s core thespians, we have Adrien Brody (of The Pianist), Ralph Fiennes (of Schindler’s List), and Jude Law (of Enemy at the Gates). All three men are famous for their roles in acceptably serious and widely acclaimed films about WWII and Nazi Germany—yet they chose this project. I like to believe it was not because they deemed the Nazis evil enough, but because they found M. Gustave particularly good.

Films with evil Nazis are not hard to come by, but M. Gustave is good in a way which is unique and fascinating; like the many paintings Anderson uses as props and scene dressings, he is equal parts marvelous and mysterious—worth staring at even if he cannot be entirely understood. And, because he would not abide discrimination and violence against his non-Aryan friend, “in the end, they shot him.” Wes Anderson’s world is in no way devoid of darkness, suffering, and injustice; that goodness and beauty is accompanied by magic and whimsy should serve a harsh reminder for the audience of just how much humanity loses where evil takes hold.