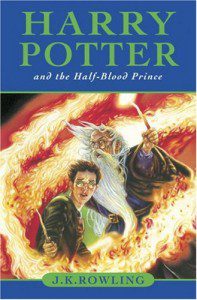

J.K. Rowling: Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Raincoast, 2005.

J.K. Rowling: Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Raincoast, 2005.

THIS IS way too eerie. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince — in which the war between the evil Lord Voldemort and the forces loyal to Dumbledore really heats up — was released July 16, almost exactly one week after the first terrorist attacks in London. And the first chapter concerns an anonymous British prime minister who wonders why his country has been hit by inexplicable acts of violence during the previous week — also in mid-July.

If it seems like a stretch to look for real-world parallels in the Harry Potter books, well, author J.K. Rowling practically invites them. Not only does the book’s very first paragraph allude to the “wretched” president of “a far-distant country” — no doubt a nod to the attitude some Brits harbour towards the Bush administration — but the story also makes frequent references to the increased security measures at the Hogwarts School for Witchcraft and Wizardry, and to the unwarranted imprisonment of innocent civilians.

And just as the present struggle requires moderate Muslims to take a stand against their extremist co-religionists, so too the only people who can stop Voldemort and his minions are his fellow wizards and witches — many of them former teachers and classmates of his.

But there are deeper themes here, too. Half-Blood Prince is profoundly concerned with the nature of love and free will, two themes that come together in one of the book’s funnier recurring motifs: love potions. Harry, Ron, Hermione and the others are 16 years old now, and there is much talk of classmates pairing off and splitting up and harbouring the silliest of crushes; Ron’s older brother even plans to marry a slightly snobbish Frenchwoman.

But the book also underscores the difference between infatuation, which a potion can provide if need be, and true love, romantic or otherwise, which sets other people free and accepts their independence. The story of how Voldemort’s parents met — and parted — is like a tragedy out of Dickens; and the book’s shocking, climactic sequence hinges on the ability of certain characters to keep their promises, some voluntarily, others perhaps not.

In this light, it is also interesting to see how Rowling describes the effects of the Felix Felicis potion, which grants good luck to the person who takes it. One character is tricked into thinking that he has taken the potion, when in fact he hasn’t — but even just the suggestion that things will go right for him prompts him to step out boldly and to achieve success through his own skills. He is acting freely, and he doesn’t know it.

What’s more, when Harry himself takes the potion, he finds that it does not change other people’s actions, but rather, it guides his own. Harry experiences a feeling of “infinite possibility”, and yet, the potion “sets a path” for him that he follows without hesitation. It is like having total freedom yet always choosing to do the “right” thing — a state which, when you think about it, must resemble what it is like to be made in God’s image, but sinless.

At least some of the characters have become increasingly complex. The wise headmaster Dumbledore is more vulnerable than he has ever been before, both physically — one of his hands seems to be permanently injured after a mysterious incident — and emotionally, his eyes watering at one point after Harry matter-of-factly professes his loyalty to him.

Harry, for his part, comes to see a new side of the bully Draco Malfoy; he still doesn’t like Malfoy very much, but for once, he begins to feel pity for him.

And Snape, the double-agent who is trusted by Dumbledore even though he was once one of Voldemort’s infamous Death Eaters, is a much more ambiguous figure than ever before. Even if Snape really is on Dumbledore’s side, you wonder how long he can go on convincing the Death Eaters that he is one of them without inadvertently convincing himself.

Those who criticize the Harry Potter books for their alleged ties to the occult will find little if any new ammunition here. As ever, the magic is little more than a fanciful and highly creative riff on modern technology; it’s like science fiction, but without any pretense of science. Ron’s brothers run a joke shop where they sell, among other things, spell-checking quills that deliberately scramble what you’re trying to write; and when Harry peers into a character’s tampered memories, the fog that obscures the edits is rather like video static.

At 607 pages, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince is pretty long for a children’s book, but it is actually the shortest entry in this series since Prisoner of Azkaban came out six years ago. Thankfully, it provides a much better pay-off than the previous instalment — the bloated, 766-page Order of the Phoenix — even as it introduces some new unsolved mysteries.

There is still one book to go. While he still has his adolescent foibles — once again, he keeps something dangerous secret for far too long — Harry is growing up, and taking charge in a battle that is much older than he is. This book shows Harry steeling himself for the battles to come, and it just may help its readers to prepare for similar challenges.

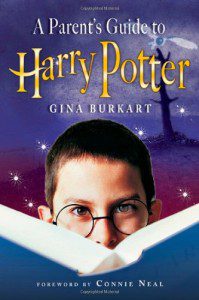

Gina Burkart: A Parent’s Guide to Harry Potter, InterVarsity, 2005.

Gina Burkart: A Parent’s Guide to Harry Potter, InterVarsity, 2005.

THOSE who thought the Harry Potter controversy had died down were a bit surprised when Life Site News, a pro-life website, declared shortly before the new book’s release that Pope Benedict XVI “opposes” the books — an exaggeration that the mainstream media was quick to pick up on. As it turns out, the Pope has said no such thing, and Catholics like Gina Burkart are joining the throngs of Christian writers who have sung the books’ praises.

It’s a measure of how quiet the controversy has become that Burkart doesn’t feel a need to address it; indeed, she says it has “subsided”. For the most part, A Parent’s Guide to Harry Potter looks at the positive role the books have played in bringing parents and children closer together, and she looks at how the books have encouraged moral reflection and spiritual growth.

The first section examines the role that stories and the imagination play in shaping how we live; Burkart also explains how children need to grow into critical thinkers and autonomous moral beings, and how learning to identify with characters in fairy tales can achieve this.

Many of her arguments could apply to any children’s books, not just the Harry Potter ones; but the boy wizard isn’t a bad place to start, and Burkart offers some fine departure points for family discussion.

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.