My interview with Katherine Orrison, who provides commentaries on the new Ten Commandments DVD, is now up at CT Movies. I might put a slightly longer version up here in a few days.

My interview with Katherine Orrison, who provides commentaries on the new Ten Commandments DVD, is now up at CT Movies. I might put a slightly longer version up here in a few days.

MAR 27 UPDATE: And here it is!

– – –

From its annual television broadcasts to its regular repackaging on home video, The Ten Commandments is not only one of the biggest hit movies of all time, it is also one of the most enduring. But what many people don’t know is that the famous Charlton Heston-starring movie, like a number of other 1950s Bible epics, was actually a remake of a 1920s silent film.

A new DVD, releasing today, aims to fill that gap. Marking the remake’s 50th anniversary, both films have been combined in a three-disc package. The first two discs are identical to the “special edition” of the 1956 version that was released two years ago; but the third disc marks the first time that the 1923 version — half of which tells the story of the Exodus, the other half of which is a morality play set in the “modern” era — has ever been released on DVD.

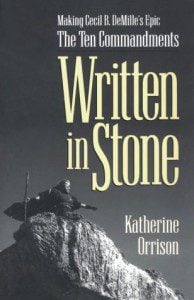

Katherine Orrison, the author of Written in Stone: Making Cecil B. DeMille’s Epic, The Ten Commandments, provides audio commentaries on both films. She spoke to Christianity Today Movies about the two films from her home in Los Angeles.

How did you get into this line of work, writing about Cecil B. DeMille and his films?

Well, it’s kind of interesting. When I was nine years old, I went to see The Ten Commandments in my small hometown, and I absolutely loved it.

What town is that?

I’m from Aniston, Alabama, now an unfortunately infamous town because the groundwater was poisoned by a chemical plant and there’s been the biggest settlement ever; in fact, I’ve been told that Aniston is more poisoned than Love Canal, if you can imagine. But back then, it was really Andy Hardy territory, and it was a typical small town, and it was a fabulous childhood — you couldn’t ask for a better place to be raised. But when I saw The Ten Commandments, I was absolutely blown away. I adored it, we all talked about it at school, I went to see it twice that week, the whole thing.

And it started me on a kind of a love of Cecil B. DeMille movies, and when I came out to California and I was studying acting, I had a friend who was taking personal voice lessons from Henry Wilcoxon, who was the producer of The Ten Commandments. And I said, “Oh, I want to meet him; oh my gracious, I’m the biggest fan.” And she said, “Absolutely.” And I went to dinner, and during dinner with him and my friend Mary, he said, “I’m looking for someone to write my autobiography.” And I said, “I’m the person! I’m the person! Nobody but me!”

So I worked with him for two and a half years on his autobiography. After he passed away, I interviewed all of his family and friends, and I completed the book [Lionheart in Hollywood] and I published it, and everyone came to me and said that their favorite chapters were the chapters on The Ten Commandments. And I said, “Well, that’s interesting, because he had a lot of information about it.” And of course, we ran it 20 times while I was with him, and we would stop the tape and he would tell me stories and I could ask questions, and I really had an incredible entrée, and through him I was able to meet the people who worked in the costuming department, I was able to meet people who acted in it, I was able to meet people who were in the sound department, just on and on. And I thought, I’ve got to do something with all this, and that’s when I sat down and I wrote Written in Stone.

You mentioned he would talk to you as you watched the tape. It sounds almost like you had your own personal audio commentary.

I did.

On some DVDs, for example the Looney Tunes DVDs, they have animation historians who sometimes use clips of recordings that they made when they interviewed Chuck Jones and people like that many years ago. Do you have any recordings of Henry Wilcoxon that you might have considered using in this?

No, there is no way. Everything that he did, he did just to me; and I know that a previous writer had made extensive tapes of him in an attempt to do his autobiography before I came along, and I listened to the tapes, and it was very interesting. Because he was an actor, and because he was so aware of the historical possibilities, he censored himself when he was on tape, and he would say, “This shouldn’t be on the tape,” and the tape would be cut off. Whereas when he and I were talking, it was a conversational thing, and I don’t think he counted on my memory being as strong as it is. And he would say things like, “Mr. DeMille was looking at William Boyd [a.k.a. Hopalong Cassidy] to play Moses instead of Charlton heston.” He didn’t say that on the tapes, I noticed, because he felt that that would be taking away from Charlton Heston, or that he might be upset that he said that. Now, my thing was, I think that that only enhances it. I think it’s fascinating to find out who he was thinking about and why he chose Charlton Heston, or why he chose Yvonne DeCarlo. But Henry was of a different mind. He also had been cautioned by DeMille to never tell anybody how the special effects were done, and in this day and age, that is what people are so fascinated by. Because of computers, because of the technical way everything has gone, and because of the way entertainment reaches us now, that is what kids want to know about.

Would you say that you are more of a Cecil B. DeMille expert, or more of a Ten Commandments expert?

Well, I would say both.

Have any of DeMille’s other films eclipsed or come close to eclipsing The Ten Commandments for you, now that you’ve seen his other films?

Well, I’ve seen all of them. I can’t say anything eclipses The Ten Commandments. But I can say that I have favorites, other than The Ten Commandments, for different reasons. I think my all-time favorite is Cleopatra (1934). I think it is absolutely beautiful. It was the first version of Cleopatra done in the sound era. It’s the only version of Cleopatra — I think there have been five or six — that turned a profit. You can’t say that about the 1962 Cleopatra! And it was a real forerunner. It was nominated for Best Picture. It had the most beautiful art direction you’ve ever seen in your life. And of course it has a stunning performance by Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Antony. In the silent era, I like the silent Ten Commandments, but I really love The Road to Yesterday (1925). And of course you can’t dismiss King of Kings (1927). It’s a beautiful, beautiful film. It holds up right up to this day. It’s been seen by more people on the face of the earth than any movie ever.

Even more than The Ten Commandments?

Yeah, yeah. Possibly because with the silent version, it could just go anywhere. You didn’t have to have anything special to show it.

Between the two different versions of The Ten Commandments, which would you say is your favorite? I got the impression listening to your commentary for the silent one, that there were a lot of things you liked about that one better, but on balance, which of the two would you say —

Oh, definitely the sound version. I mean, it’s always going to have my heart. But the thing is, I’m hoping that what comes across in my commentary on the silent version is my love of silent film. I think people dismiss it, and they say, “Oh, it doesn’t have sound, so it can’t be any good,” and I think that’s a hundred percent wrong. I think sound film and silent film are two different arts. And something that works in a silent film won’t necessarily work in a sound one, and vice versa. But silent film is universal. You don’t need to speak the language to know what’s happening. And if you can tell a movie visually, that’s what movies are all about. And I think that’s why the silent-movie directors who moved into sound were so superior to their contemporaries who came out and started working in sound right off the bat. The visuals of a silent film are always so stunning, and the acting is so clear; you see it on their faces, you know what the people are thinking and what they’re feeling, and you are pulled along by what’s going to happen next, because you’re a participant too — you’re having to add something to the film to watch it.

When I saw the silent version on VHS, the Exodus sequence was in Technicolor — two-strip or Process 2 Technicolor —

It was. It was.

— and yet the DVD seems to have just straight black-and-white all the way through, and then as a bonus feature, they show the Exodus in hand-tinted colour.

Oh, I didn’t know that, because what they ran for me was the black-and-white. I know that the two-strip Technicolor degenerated to a great degree, and they said that they didn’t have a colour version that was good enough to put on the DVD. I have seen it, but it was, like, decades ago that I saw the colour version included with the black-and-white. But I didn’t know about the hand-tinted. There were two different ways of doing it in the silent era. You could hand-tint, or they were experimenting with the two-strip Technicolor in the early ’20s. . . . I feel that any kind of colour enhances the whole idea of it. Especially, for instance, with the pillar of fire, when the horses are stopped by the fire. I can see how that would work beautifully and really awe and inspire the audience that would be seeing it in 1923. I wish I’d seen the tinted sequence! I didn’t.

They actually include the fire with the horses in the bonus feature.

Oh boy! I’m glad to hear that! I’ve got to go get the DVD. It’s not out yet, I have to wait —

They didn’t send you a copy?

No! And I have to wait ’til Tuesday, when it’s out. Then I can buy one!

If I’m not mistaken, the commentary on the 1956 film is the exact same one that you recorded two years ago for the other special edition, so I’m kind of curious, when you were approached to do that and basically they told you you had to provide commentary for a four-hour movie, did you panic? Did you think, “How will I fill the time?” Or did you have so much material that you were still wondering what to include?

I had so much material — and it was in my head, because of writing these two books and because of spending so much time with Henry Wilcoxon — that I had to leave a lot out. I was trying very hard to stay in a scene — I didn’t want to be talking about one scene when we’d already gone on to something else — and I only got to do one take. And I got one break, and that was when the film breaks, when Moses is banished to the desert, and in theatres, you had intermission. That was when they stopped, and they said, “Okay, you can have lunch, and then we’ll do the second section in the afternoon.” But they started it, and I had to start talking, and I had to go straight through. So I did it in two-hour sections, the first section in the morning and the second section in the afternoon, and like I said, there were a lot of things I wanted to say or thought about saying that I would just have to move along and not be able to get in. But I said to them, “Do you want me to write this out?” And they said, “We don’t think you can write a four-hour commentary out.” I said, “You’re right.” They said, “It will be much better if you just do it as you’re watching the film.”

How do you choose what to focus on? On one hand, you can talk about how the movie was made and all kinds of behind-the-scenes stuff. On another level, you can also talk about the religious content and the significance of all that. And then of course there’s the political content; you mentioned the civil rights movement of that era, but I’ve also heard people talk about the clash with Communism, and there’s that opening speech that DeMille gives at the beginning of the film where he pretty clearly alludes to the fact that he sees Rameses as essentially an almost Stalin-like dictator. So there’s all these other elements that could be gotten into.

I absolutely agree with you. On the DVD, is the opening shown, with DeMille coming out from behind the curtains [before the opening credits of the 1956 version]?

Yes it is.

When I was shown the film, I said, “Where’s that opening, because I had these things that I want to say about that,” exactly what you just said, and they said, “Oh, that’s not going to be on the DVD.”

Oh! I noticed that there was no commentary there —

That’s it, that’s why there’s no commentary. Again, I have not had a chance to sit down and look at it since they made it, and I thought it was very important to be able to talk about why DeMille was making The Ten Commandments at that time, and they said, “No, you’ve got to start right at the credits.” In my mind, I had prepared about three minutes on that very subject, and I had to immediately throw it out of my mind and go right into “These are the titles and the titles were done by Arnold Friberg etc., etc.” But I sort of tried to move back and forth as the movie went along, and I know that I didn’t talk about how many people were in the Exodus or any of that because that’s been hit so many times, and I felt that it was important to show how much DeMille loved the people who worked for him, and how loyal he was, and the fact that he used H.B. Warner in that Exodus sequence, because he had played Christ in King of Kings.

Can you remember what you were planning to say in those three minutes?

I can remember that I wanted to tell people a short little thing on DeMille’s background, the fact that it was his last movie and it was most successful movie, because he was putting his money where his heart was, and that he truly cared about making this movie. It wasn’t a question of making a buck, it wasn’t because he thought it was a fashionable thing to do — rather, in many ways, it was an unfashionable thing to do — but he wanted people to know that he was very serious about this movie, that he had purposely gone to the Holy Land to film it where it had happened, that he had done extensive research.

I had someone tell me, just last week, “Well, how did DeMille change the Exodus story to make it a Hollywood movie?” I said, “He didn’t change the Exodus story at all. He did years and years of research.” There are things we know now about the Exodus time as a result of finding the KV5 in 1996 in the Valley of the Kings, but everything that was in it was right up to the moment. And there was so much research on this movie, that they published a book on the subject, Moses and Egypt, in 1956, which was by his researcher, Henry Noerdlinger.

So DeMille was sincere. And I think that when he comes out from those curtains and he speaks to the audience that way — which nobody, nobody ever began a movie that way, and no one has done it since — he wanted people to know, “I take this very seriously, this is not going to be a Hollywood salacious movie,” and he wanted people to know the researchers that he had used and the texts that he had used, and that what you’re going to see is to the best of our knowledge as close to the way it really was as possible.

So he really had a message he was trying to get across?

Absolutely. And that message was that all peoples in all eras have been slaves. All of us, all of us, have slavery in our background. The Greeks were slaves to the Romans, the Egyptians were slaves to the Babylonians, we can go all down through history, the Irish — which is what I am — were slaves to the English. And all people have fought to be free. And you can put men’s bodies into bondage, but you can’t put men’s minds into bondage. They will always seek to find God and to go their own way. And the thing about the era of the 1950s was, of course, Communism said there is no God. They completely eliminated all religion from the holy Russian empire, and I think that’s why it fell. I sincerely believe that’s why it couldn’t last. Because the Russian people were so religious, the Russian Orthodox Church was such a large part of their lives for century upon century, and then to say, “Oh it’s all nonsense and we’re throwing it out and we’re closing the churches and there is no God–“

You also mention in both your commentaries that there is also this theme that if you break the Ten Commandments, the Commandments will break you.

That’s right. And DeMille would sign his autographs that way. During that era, when he would go to the premieres of The Ten Commandments, and he would speak beforehand and people would come up and ask for his autograph, that’s what he would sign.

He would actually say, “they will break you”?

Yes, and there were two autographs. There was, “See The Ten Commandments, keep the Ten Commandments.” And then, “If you break the Ten Commandments, they will break you. Cecil B. DeMille.” Rather than “Best regards” or “It’s so nice to meet you” or “Love, Cecil B. DeMille,” that is what he would sign.

Why do you think the film has this enduring popularity, that it’s shown every year and people keep talking about it and seeing it? Why has it survived?

I think it’s survived for a variety of reasons, because there have been other versions made, and ABC is running a new version next month, and I had the New York Times say, “Oh, well, this is going to be a gritty, realistic, relevant-to-the-day telling of The Ten Commandments,” and I said, “Yes, that’s been done several times before, and it’s never found an audience.” And they didn’t know that Ben Kingsley had played Moses [in TNT’s Moses, 1996] or that Burt Lancaster had played Moses [in CBS’s Moses the Lawgiver, 1975] and that this had happened. This one survives for a variety of reasons. I think it survives because it has something for everybody. Children can sit and watch it and just be caught up in the old-fashioned Bible story, like they’re sitting at a Sunday school lesson, except it’s so visual. Older people can watch it and enjoy seeing the stars of their era, in probably the best presentation possible — the florid colour, the wide screen and the stereophonic sound, the beautiful score to this movie.

I listen to it a lot, actually.

The score is fantastic, it just sweeps you along. You can hear the score without seeing the pictures and know what’s happening. It’s a kind of a silent movie score in that way. You don’t have to be able to speak the language to know what’s happening, because the actors have this wonderful 19th-century Easter-pageant presentation way of doing it. It’s just fun! I’m never bored. I always see something new every time I watch it.

Do you think the silent version is still relevant today?

Yes, I think it’s very relevant. I love silent movies, I absolutely love them. And I think that there’s a lot to be learned from silent movies, because it’s the only opportunity in history that we’ve had to actually go back in time and see the way that people lived, thought, and behaved. We sit here in 2006, and we can actually go back to 1923 and we can see exactly how they dressed; we can see how their houses were; we can see what their relationships were with their family, with their friends, with their wives, with their husbands; we can see the mores of the time; and at no other time have we been able to look back a hundred years and see how people really were. Prior to the 20th century, for a couple of decades, you had photography, but that didn’t show you how people lived. They were sitting in their best clothes, they’re sitting stiff, they have a bright light go off in their face, they have to sit still for three minutes to be able to take the photograph — that doesn’t show you their life, it just shows you a likeness of their body at that time. But when moving pictures came in and they shot on the street and they shot in people’s houses and they shot in public buildings and they made movies about their lives — Griffith was very good at making movies about the social oppression of the ‘teens, about World War I. Never before were they able to go on a battlefield, shoot an actual battle, and show people dying right in front of the camera. It is a time machine, and I think for that reason, it’s important to see what came before so that we don’t make the mistakes of the past.

In your commentaries, you mention that, when you were a child, you actually put blood on the doorposts.

Yeah, I did — lamb chops!

Do you still do that?

Yeah! Yes, I go and I buy a lamb chop every Passover, and I do the little lamb’s blood — not big, you know, a couple of drops — but it’s something I always do. And then I sit down and watch The Ten Commandments. And with ABC running The Ten Commandments usually on Passover, it’s really a perfect thing to do. It’s become tradition in my household, and I know the neighbourhood thinks I’m crazy, but I did it when I was a little girl because I was so scared. I was a firstborn! And when I saw that firstborn angel coming, it terrified me. It really truly did, and I was just insistent, and Mother was horrified and she would wash it off!

And you also mentioned that you live in a building that was built by DeMille in 1928.

Yes, it was. A lot of the wonderful old buildings in Hollywood were built by the DeMille family as income property. And also there are a lot of buildings in West Hollywood and Hollywood proper that were provided for the studio workers, so that when they came out from New York or came out from Chicago — because they were calling on a lot of the stagecraft from back east — that they had affordable living and they had transportation that was nearby. In the case of where I am, Santa Monica Blvd. is just a half a block above me, and that had the trolley car that ran straight to the studios. So I’m certain that this was built at one time as income property for his workers, and if you go to the city hall and you go to the records, you can find out who built a building and who owned it and who bought it from who, and Cecil B. DeMille was the builder of this particular building. It’s kind of an Italian duplex.

So what do you think he’d say if he knew that you were dabbing lamb’s blood on the door every Passover, in his building?

I think he would be very pleased! If I know him, he would be very pleased, and he would say, “Thank you for the compliment.”