On at least two occasions this year, I have grumbled about the relative lack of movies about the prophet Elijah.

On at least two occasions this year, I have grumbled about the relative lack of movies about the prophet Elijah.

He’s a very important figure in the Bible: not only is he one of two Old Testament figures who went straight to heaven without dying (the other is Noah’s great-grandfather Enoch), he is also one of only two Old Testament figures who appear with Jesus at the Transfiguration (the other is Moses). The Old Testament prophet Malachi predicted that Elijah would return before the great day of judgment, and Christians believe this prophecy was fulfilled by John the Baptist, while Jews set a cup of wine aside at the Passover table in anticipation of Elijah’s return.

But has Elijah received the same sort of cinematic attention as Moses and Jesus? Have there been any epic blockbusters about his confrontations with the prophets of Baal and their royal patrons, King Ahab and Queen Jezebel? Alas, no.

But that’s not to say there haven’t been any films about Elijah. There are, in fact, a variety of short films and other shows that have covered these subjects, and yesterday I finally got around to watching the one feature-length film version of his story that was produced during the 1950s, when the Bible-movie genre was at its peak.

Alas, the film in question, Sins of Jezebel (1953), is not very good. But the fact that it’s pretty much the only film of this pedigree about these characters makes it an interesting artifact even so. And it has some other quirks besides. So, here are some thoughts on the film, the YouTube version of which is embedded here.

Biblical authority. The film begins with a harmonized version of the creation stories in Genesis and then — after showing us the Narrator, who dresses and speaks like a minister of the period — it tells us about the Ten Commandments that were given to Moses. So from the very beginning, the film emphasizes the Bible’s authority as a source for both narrative material and commandments to live by.

The funny thing is, despite this appeal to the Bible’s authority, the film actually deviates from the biblical narrative in all sorts of ways, big and small. In one scene, the Narrator even stands over what looks like a Bible and tells us about all the things that Jehu did while Ahab was king — but none of those deeds are actually mentioned in the Bible. (Jehu was one of Ahab’s officers, and God mentions Jehu’s name to Elijah during Ahab’s reign, but Jehu himself does not become an active character within the Bible until years after Ahab’s death.)

The film even goes so far as to link the Narrator with Elijah himself in at least three ways: First, they are played by the same actor. Second, at one point a shot of the Narrator’s shadow dissolves into a shot of Elijah’s shadow as he confronts Ahab, and then, at the end of the sequence, Elijah’s shadow turns into the Narrator’s shadow again. And third, at the very end of the film, the Narrator tells us that prophets like Elijah pass their mantles on to others — at which point the camera pans down to the cane in the Narrator’s hand as he leaves the room, which seems to me to hark back to the staff that Elijah holds in his hand throughout the film. So the film suggests that the authority of the Hebrew prophet is, in some way, transmitted through modern-day ministers who expound on the story of that prophet (even if, in the movie’s case, the minister tells a somewhat altered version of that story).

The film even goes so far as to link the Narrator with Elijah himself in at least three ways: First, they are played by the same actor. Second, at one point a shot of the Narrator’s shadow dissolves into a shot of Elijah’s shadow as he confronts Ahab, and then, at the end of the sequence, Elijah’s shadow turns into the Narrator’s shadow again. And third, at the very end of the film, the Narrator tells us that prophets like Elijah pass their mantles on to others — at which point the camera pans down to the cane in the Narrator’s hand as he leaves the room, which seems to me to hark back to the staff that Elijah holds in his hand throughout the film. So the film suggests that the authority of the Hebrew prophet is, in some way, transmitted through modern-day ministers who expound on the story of that prophet (even if, in the movie’s case, the minister tells a somewhat altered version of that story).

Biblical references. I’m always intrigued when a Bible film indicates its awareness of stories from other parts of the Bible. In this case, we are told that Naboth can remember how Jehu and his father used to hide from Jeroboam’s soldiers when Jehu was a boy; apparently Jehu’s father worshipped Jehovah and had to flee for his life while Jeroboam was promoting the worship of idols.

This is a highly unlikely scenario, if only because Jehu, who became king of the northern kingdom of Israel around 840 BC, lived decades after Jeroboam, who rebelled against Solomon and ultimately led the northern tribes in breaking away from the kingdom of Judah sometime around 930 BC. The thought that Jeroboam could have persecuted Jehu’s father seems like a bit of a stretch; there was at least one extra generation, and maybe two, between Jeroboam and Jehu.

Still, it’s impressive that the film mentions Jeroboam in the first place, and the way it beefs up the part of Jehu is at least interesting in theory, if not in execution.

There may be another creative mingling of texts near the film’s conclusion. The last time we see Elijah, he anoints Jehu king of Israel and then appoints Elisha — a character we’ve never seen before — to be his own prophetic successor. This is different from the chronology presented in the book of II Kings, where Elijah ascends into heaven and leaves the pages of history in chapter 2, and then Elisha sends yet another prophet to anoint Jehu some time later in chapter 9.

There may be another creative mingling of texts near the film’s conclusion. The last time we see Elijah, he anoints Jehu king of Israel and then appoints Elisha — a character we’ve never seen before — to be his own prophetic successor. This is different from the chronology presented in the book of II Kings, where Elijah ascends into heaven and leaves the pages of history in chapter 2, and then Elisha sends yet another prophet to anoint Jehu some time later in chapter 9.

But perhaps the filmmakers weren’t simply rewriting the Bible willy-nilly. It’s possible they actually had in mind an even earlier passage, in I Kings 19, when Elijah goes to Mt Sinai and God instructs him to anoint Hazael king of Syria, Jehu king of Israel, and Elisha as Elijah’s own successor. Biblically speaking, the original commandment to anoint Jehu was given to Elijah, but for some reason he never got around to it. So perhaps the filmmakers wrote this scene — in which Elijah personally appoints both Jehu and Elisha — as a more direct fulfillment of that command from God.

Sexual politics. The name “Jezebel” had come to mean a sexually promiscuous woman long before this movie came out, so it’s not too surprising that the movie turns the actual biblical Jezebel, who never does anything particularly sexual, into something of a temptress and an adulteress from just about her very first scene.

What is surprising, to me at least, is that the film has Jezebel carry on an affair with Jehu behind Ahab’s back. This, despite the fact that Jehu would go on to be the general charged by God’s prophets with the mission of wiping out Ahab’s family and taking its place on the throne. The movie doesn’t get into all of the pertinent details in the end — it never even acknowledges that Ahab and Jezebel had children — but it does have Jehu take over the country, and the fact that he comes back as a soldier for God while Jezebel receives an ignoble death does seem a bit sexist, as though the man could be forgiven for his sexual indiscretion but the woman could not.

There is, admittedly, one tiny detail in the Bible that might lend some support to a romantic link between Jehu and Jezebel. When Jezebel heard that the king of Israel (her son) and the king of Judah (her grandson) had been killed by Jehu, and that Jehu was riding his chariot into her city, she “put on eye makeup, arranged her hair and looked out of a window.” Some people have supposed that she was trying to seduce Jehu, but given that the very first thing she does after fixing her appearance is taunt Jehu, by comparing him to a previous assassin who died within days of his coup, I suspect she was simply trying to look authoritative, like a queen.

There is, admittedly, one tiny detail in the Bible that might lend some support to a romantic link between Jehu and Jezebel. When Jezebel heard that the king of Israel (her son) and the king of Judah (her grandson) had been killed by Jehu, and that Jehu was riding his chariot into her city, she “put on eye makeup, arranged her hair and looked out of a window.” Some people have supposed that she was trying to seduce Jehu, but given that the very first thing she does after fixing her appearance is taunt Jehu, by comparing him to a previous assassin who died within days of his coup, I suspect she was simply trying to look authoritative, like a queen.

The film’s underlying misogyny is evident in other ways, too. A chariot repairman complains that the vehicle he’s working on is “worse than a woman.” A woman dances sexily before the idol of Baal, inviting the modern-day audience to both enjoy the sight of her sexiness and to condemn her for being part of the evil on display.

And Ahab, much to my surprise, is made out to be something of a petulant, vulnerable, foolish beta male who is clearly so desperate for Jezebel’s love that he is easily manipulated by her. So when, at the beginning of the film, the Narrator tells us that “there was evil again in the land, and a woman behind that evil,” the blame is not shared equally by the king and queen who built the temple to Baal; instead, it seems to rest primarily, though not quite exclusively, on the queen.

And what a poor sap Ahab is! In his very first scene, he’s whining to Elijah and the elders about how he is “a man of flesh and blood. I will not be denied my human feelings!” And then, when Jezebel arrives at his court, he is absolutely smitten by her but tells her that he cannot go to her chambers until after their wedding — but when he remembers that he forgot to give her a special necklace, he sends Jehu to her chambers to give it to her in his place! (Not surprisingly, that’s when the affair between Jehu and Jezebel begins.) And then, on their wedding night, Ahab makes a big show of how much he wants to be wanted by Jezebel — but as soon as he seems to have won her favour, he falls asleep on the floor next to their bed. Notably, Jezebel does not seem to mind at all that she won’t have to sleep with him right away.

And what a poor sap Ahab is! In his very first scene, he’s whining to Elijah and the elders about how he is “a man of flesh and blood. I will not be denied my human feelings!” And then, when Jezebel arrives at his court, he is absolutely smitten by her but tells her that he cannot go to her chambers until after their wedding — but when he remembers that he forgot to give her a special necklace, he sends Jehu to her chambers to give it to her in his place! (Not surprisingly, that’s when the affair between Jehu and Jezebel begins.) And then, on their wedding night, Ahab makes a big show of how much he wants to be wanted by Jezebel — but as soon as he seems to have won her favour, he falls asleep on the floor next to their bed. Notably, Jezebel does not seem to mind at all that she won’t have to sleep with him right away.

Still, all that being said, I thought Ahab did offer an interesting defense of Jezebel in his very first scene, when one of his advisors passes on a rumour that Jezebel dips her fingers in the blood of her sacrificial victims, and Ahab replies that the colour on her hands is actually henna. There’s just a hint there that Jezebel’s reputation might have been the product of Israelite xenophobia, but the film never follows up on it.

And of course, not all of the women here are bad. Naboth’s daughter Deborah is presented as the “nice girl” that Jehu ought to be with instead of Jezebel. And when Jehu asks why Deborah considers Jezebel “evil”, Deborah replies, “Because I am a woman. Perhaps I can see things in another woman that a man cannot see.”

Historical details. In addition to beefing up Jehu’s role far beyond what the Bible describes, the film also makes curious tweaks to the parts of the biblical narrative that it does present more straightforwardly.

Historical details. In addition to beefing up Jehu’s role far beyond what the Bible describes, the film also makes curious tweaks to the parts of the biblical narrative that it does present more straightforwardly.

Most significantly, the famous contest between Elijah and the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel (described in I Kings 18) is now presented not as a challenge posed by Elijah from the very beginning, but as a ceremony initiated by Jezebel and the prophets of Baal, which Elijah then interrupts.

Even stranger, Elijah now uses the very same altar that the prophets of Baal had used, which not only contradicts the Bible’s claim that Elijah repaired an altar to Jehovah that had been torn down some time earlier, but also seems highly unlikely in light of the spiritual significance that people in the ancient world attached to physical objects. Stones offered up to Baal would not — could not — be used in God’s service mere minutes later, especially if one was engaged in a contest to prove that one set of burnt offerings would get a response and the other would not.

The film also fails to deliver on the punchline to that contest. In the Bible, Elijah does not burn the offering himself, but asks God to light the sacrifice instead — and God does! (This is one of a few miracles associated with Elijah that involve fire from heaven; see also the death of the soldiers who try to arrest him in II Kings 1 and the fiery chariot that takes him up to heaven in II Kings 2, neither of which appear in this movie.) But in the movie, Elijah’s prayer is answered instead by rain — which does, indeed, come up at a slightly later point in the biblical narrative, but still.

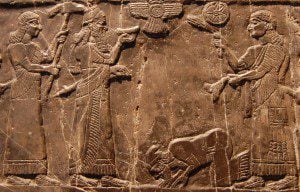

A few other historical quibbles: Ahab talks about the need to build up his dynasty, which he refers to as “the house of Ahab”. However, the Israelite dynasty to which he belonged was actually named after his father Omri, and archaeologists have found inscriptions from the neighbouring countries that refer to Israel as a whole as “the house of Omri”, apparently because Omri and his descendants made a big impression on their neighbours. (Even Jehu, who killed all of Ahab’s heirs, is referred to in one Assyrian inscription — seen here — as “the son of Omri”; scholars disagree as to whether this means Jehu came from a different branch of Omri’s family or simply that Israel had become so identified with the Omrid dynasty that even the post-Omrid kings were given that name.)

A few other historical quibbles: Ahab talks about the need to build up his dynasty, which he refers to as “the house of Ahab”. However, the Israelite dynasty to which he belonged was actually named after his father Omri, and archaeologists have found inscriptions from the neighbouring countries that refer to Israel as a whole as “the house of Omri”, apparently because Omri and his descendants made a big impression on their neighbours. (Even Jehu, who killed all of Ahab’s heirs, is referred to in one Assyrian inscription — seen here — as “the son of Omri”; scholars disagree as to whether this means Jehu came from a different branch of Omri’s family or simply that Israel had become so identified with the Omrid dynasty that even the post-Omrid kings were given that name.)

Ahab also tells Jehu that he, Jehu, is lucky he was not “born to the crown” — but Omri, a former general who came to the throne following a civil war with generals Zimri and Tibni, reigned for only 12 years, so if Ahab was already an adult when he took the throne himself, then he would have been born before his father was king.

In fact, in the history of Israel to that point, very few kings had been born to the throne. The united kingdom of Israel was ruled by Saul, David and Solomon, only one of whom was actually born into a royal family. Jeroboam led the northern tribes in breaking away from the tribe of Judah (which continued to be ruled by David’s dynasty) and his son was assassinated almost as soon as he became king. The man who assassinated him, Baasha, ruled for a couple decades and then his son was assassinated almost as soon as he became king. And then came the civil war that led to the establishment of the Omrid dynasty of which Ahab was a part.

Ahab was, in fact, the first son of a king since Solomon to rule over the northern tribes for more than a couple years — but since, as I noted above, it is very unlikely that Ahab was an heir to the throne at the actual time of his birth, the political situation in Israel was still arguably in a state of flux, and I suspect Ahab would have been well aware of that. In fact, the marriage of Ahab to Jezebel, whose father was the king of Sidon, might very well have been intended partly to shore up the Omrid dynasty’s claim to regal status; at the very least, it would have been a political alliance as much as anything else, as even the movie’s Ahab states.

Ahab was, in fact, the first son of a king since Solomon to rule over the northern tribes for more than a couple years — but since, as I noted above, it is very unlikely that Ahab was an heir to the throne at the actual time of his birth, the political situation in Israel was still arguably in a state of flux, and I suspect Ahab would have been well aware of that. In fact, the marriage of Ahab to Jezebel, whose father was the king of Sidon, might very well have been intended partly to shore up the Omrid dynasty’s claim to regal status; at the very least, it would have been a political alliance as much as anything else, as even the movie’s Ahab states.

One other significant deviation from the history of the period is that Ahab promises his fellow Israelites that Jehovah will be their only god, until Jezebel convinces him otherwise. Since the film acknowledges that Jeroboam worshipped idols sometime before this, it would seem that the northern tribes must have turned back to Jehovah at some point — but the biblical record indicates otherwise. In fact, one of the points that the Book of Kings harps on is that every single king who ruled over the northern kingdom of Israel worshipped idols of one sort or another; Ahab, by adding the worship of Baal to the mix, was simply the worst of those kings.

Less significantly, the Narrator tells us that Ahab was killed by “a Syrian sword”, when in fact it was an unaimed arrow that killed him. The film does have Jezebel killed with an arrow, though, apparently against Jehu’s wishes, but that too is a deviation from the biblical account, where Jezebel’s eunuchs toss her out of a window at Jehu’s command. (In the film, her body is tossed off the balcony by bitter rebel soldiers who refuse to give her a proper burial after she has been killed.)

Contemporary resonances. When Jehu walks out of the Baal ceremony, Jezebel suggests that the “pulse beat” of the music might have made him lose self-control. This film was made a few years before the invention of rock’n’roll, but it’s possible to see in this a concern over the proliferation of jazz and similar forms of music.

Perhaps the most striking line comes from Naboth, who is helping the followers of Jehovah to hide in the caves from Jezebel’s soldiers. “Perhaps,” he says, “exile is the fate of our people. What we suffer, others have suffered before us. And still others of our race will suffer in the years that are still to come.” This film, remember, was made only eight years after the end of the Holocaust, and five years after the creation of the state of Israel and the first Arab-Israeli War.

Perhaps the most striking line comes from Naboth, who is helping the followers of Jehovah to hide in the caves from Jezebel’s soldiers. “Perhaps,” he says, “exile is the fate of our people. What we suffer, others have suffered before us. And still others of our race will suffer in the years that are still to come.” This film, remember, was made only eight years after the end of the Holocaust, and five years after the creation of the state of Israel and the first Arab-Israeli War.

Note also how the Narrator describes the caves in which Elijah’s followers hide as a “stronghold for the voice of freedom”. I’m not sure that the Bible or the ancient Israelites would have framed their struggle that way, but it is the sort of language that would appeal to an American audience with its history of struggles for “liberty”, etc.

Finally, I cannot help but be amused by the fact that the Narrator’s replica of the Baal idol, which he points to whenever he cites the commandment against graven images, is sitting beneath a stained-glass window. There are some Protestants who believe that the commandment against graven images applies to any and all visual artforms, including stained-glass windows — but I guess this Narrator isn’t one of them.

Odd dialogue, odd music. My favorite bit of dialogue has to be the exchange between Ahab and Jezebel on their wedding night, when she says, “I have no kingdom to give. I am only a woman,” and Ahab replies, “That is kingdom enough for me!”

I also laughed when Jehu tells Deborah, “In battle or peace, people get hurt. People get hurt just living.” Jehu’s line delivery makes the line sound even more pathetic than it must have looked on paper.

I also laughed when Jehu tells Deborah, “In battle or peace, people get hurt. People get hurt just living.” Jehu’s line delivery makes the line sound even more pathetic than it must have looked on paper.

For its part, the music feels at times like it’s evoking the theme to Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson & Delilah (1949), which came out four years earlier and thereby kicked off the first significant wave of Bible movies since the silent era.

And I thought it was fairly strange how the soundtrack laid on a bit of pious choral music when Elijah declares that there will be no dew or rain on the earth as punishment for Ahab’s worship of Baal; you would think that this threat should come across as ominous or something, but the music goes in a completely different direction. It sounds, in fact, like the kind of choral music that Monty Python sometimes adds to its parodies of these sorts of movies.

Casting connections. Jezebel is played by Paulette Goddard, who had previously been married to Charlie Chaplin and had co-starred in two of his films, Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940). This was one of her last films.

Jehu is played by George Nader, who played the lead role in the infamous 3D sci-fi movie Robot Monster (1953) the very same year that Sins of Jezebel came out.

King Ahab is played by Eduard Franz, who would go on to play Jethro in The Ten Commandments (1956) and someone named Jehoam in The Story of Ruth (1960).

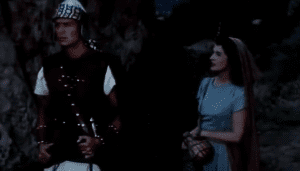

And both Elijah and the Narrator are played by John Hoyt, who would go on to play the ship’s doctor in the original Star Trek pilot ‘The Cage’ (1964). And who played the captain of the Enterprise under whom that doctor served? Jeffrey Hunter, who had previously played Jesus in King of Kings (1961)! So whenever I see that Star Trek episode again — or ‘The Menagerie’, a two-parter that used footage from ‘The Cage’ — it won’t be Captain Pike and Doctor Boyce meeting onscreen, it will be Jesus and Elijah. At least for me!

And both Elijah and the Narrator are played by John Hoyt, who would go on to play the ship’s doctor in the original Star Trek pilot ‘The Cage’ (1964). And who played the captain of the Enterprise under whom that doctor served? Jeffrey Hunter, who had previously played Jesus in King of Kings (1961)! So whenever I see that Star Trek episode again — or ‘The Menagerie’, a two-parter that used footage from ‘The Cage’ — it won’t be Captain Pike and Doctor Boyce meeting onscreen, it will be Jesus and Elijah. At least for me!

Update: My friend Matt Page reviewed the film five years ago at his Bible Films Blog, and he makes some excellent points there that hadn’t occurred to me yet, such as how the film all but obliterates the striking humanity of the biblical Elijah.