I had a conversation three weeks ago with a remarkable man. His name is Antoine Rutayisire, and his words have been haunting me ever since we spoke. I sincerely doubt they will ever leave me alone.

I had a conversation three weeks ago with a remarkable man. His name is Antoine Rutayisire, and his words have been haunting me ever since we spoke. I sincerely doubt they will ever leave me alone.

Antoine is an Anglican priest and a survivor of the racially-motivated Rwandan Genocide, and I was tasked to interview him for the new FULLER magazine.[1] I have to admit: I knew of the genocide, but I did not know about the genocide. I literally had five minutes from receiving the assignment before meeting Antoine for the first time, so I did my research before our second talk.

It is difficult to read about a great evil, but I think it was even worse to read the history knowing a man who had lived it. The first-hand accounts of what happened were horrible, and it is unfathomable how people could do this to other people. I am by no means trying to take a righteous moral high ground; I am saying that the genocide defies description or even quantifiers for how bad it was. The numbers can give some sort of picture: between April 7 and July 4 of 1994, 1.174 million people were killed, typically with bullets and traditional hand-weapons. That’s seven people exterminated every minute for those 100 days.

These horrors cannot be put into words.

Meeting Antoine the second time, his country’s history playing through my mind, I had a hard time keeping it together. Antoine has seen horrible, horrible things, but he speaks with and of hope. He does not pretend that evil has not happened, but instead looks to ways of partnering with God to set this world to rights, of healing racial wounds, of rebuilding with love and forgiveness a nation ripped apart by hate and fear. He is hopeful and confident, convinced that God can and will overcome even this dark evil of genocide, a crime that was—I am sorry to say—participated in by churches in Rwanda.

Antoine suggests that the church developed blind spots, blind spots that allowed and helped commit terrible tragedy. But he also insists that all churches develop blind spots. I spoke of how sad it is that so many of us have no idea how bad it is here, there, everywhere.

“Well,” Antoine responded, “It is, I think, a blessing that we are all limited to one place and time. We could not hold all the sorrows and troubles of the world if we knew or saw them all. But you are right: we must open our eyes, we must undo our blind spots, we must see where injustice exists in our communities and work against it. We are responsible for those places where God has planted us. We must be the pastors and evangelists who transform our communities.”

Then he said those words that won’t leave me alone.

“One day, Reed, you will have to stand before God and answer for what has happened in Pasadena. I will stand before God and answer for Rwanda.”

I can’t get those words out of my head. Not because I think I will solely bear the weight of all the evil that has happen in Pasadena, nor do I think I got the bum end of the deal; the idea of answering for Rwanda makes me quake. No, what hits me here is the responsibility, the awe, the dread.

This is the weight of our call.

It is like a master, before going on a long journey, summoning his servants and entrusting his property to them. To one he gave five talents, to another two, to another one, each according to the servant’s ability….

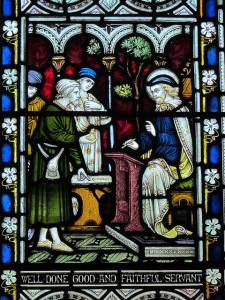

The Master is coming back at some point, and those of us who have been entrusted with proclaiming the Good News, with working for peace, with standing against injustice—all those who are Christians—will have to answer our Master on how and where we spent our talents.[2] Yes, there is heaviness here, but there is also empowerment. This distribution was done according to each one’s ability, the evangelist tells us. We are given a difficult task, but with the understanding that we can accomplish it with and through the grace of God. The question is, will we? Will we do the difficult and brave thing, like Antoine has chosen to do? To rebuild Rwanda? To heal Pasadena? To fight racism and bind up the broken-hearted, to proclaim release to the captives and stand against the injustices of this world? Will we preach and live the Good News?

This is the challenge that Antoine left me with, the fire that burns in my bones. My prayer is that all of us may open our eyes and remove those blind spots, enacting change and transformation in our communities for the glory of God. May we one day stand before the throne and hear, when all is accounted for, “Well done, good and faithful servant,” not for our own sake, but for those individuals, communities, and nations that have been entrusted to our care.

Reed Metcalf works as a Media Relations and Communications Specialist at Fuller Theological Seminary. He writes for and curates the Fuller Blog and contributes regularly to FULLER magazine. He graduated with his MDiv from Fuller in 2014 and is an ordination candidate in the Free Methodist church. When not neck deep in biblical languages, theology, and writing, Reed is often surfing, skating, or hiking with his wife Monica. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram at @reedmetcalf.

[1] The feature story on Antoine should be out in Issue #3 of FULLER. Keep an eye out for it in Spring 2015.

[2] I understand that the historical and literary context of Matthew 25 suggests that this parable might be aimed at those in the Jewish leadership that were insincere, unfruitful, and or corrupt, warning of their judgment in the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 CE and in the resurrection. As I also understand the Bible to be God’s Word to the community of believers (even today’s community of believers despite the chronological and geographical distances to the original context of the Scripture), I see this is be a plausible contemporary reading of the text with the traditional critical concerns incorporated.