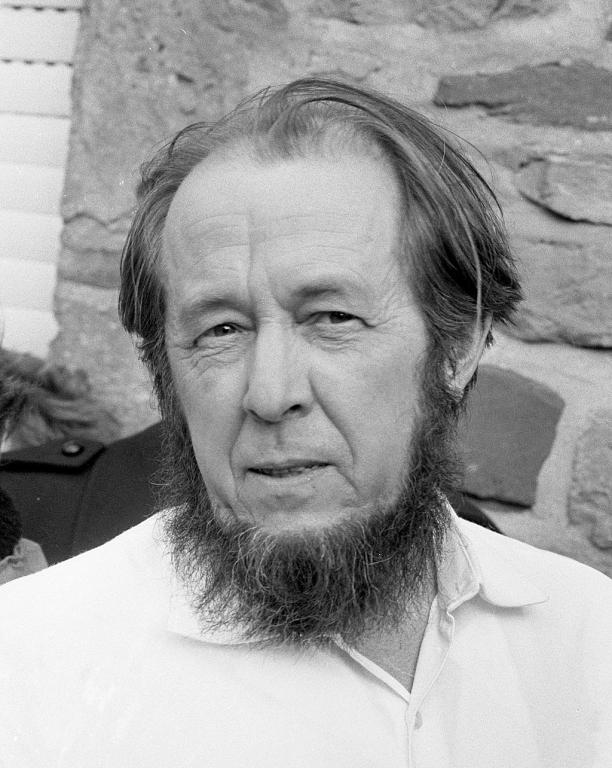

The Russian novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation” exposed the evils of Soviet Communism by documenting the atrocities in the Soviet prison camps, where he himself was confined for nearly a decade. Another theme in that three-volume exposé was how he himself was converted to Christianity.

Gary Saul Morson, a professor of Slavic literature at Northwestern, tells about how that happened in his article for the Wall Street Journal [behind a paywall] entitled How Solzhenitsyn Found Himself—and God.

Solzhenitsyn was hardly a dissident when he was arrested and sentenced to an arctic prison camp for ten years of hard labor. He was a committed Marxist who was serving as a captain in the Soviet army that was invading Germany when he was arrested for letters he had written to a friend criticizing Stalin’s conduct of the war. For that he was sentenced to eight years in a prison camp, plus permanent exile in Siberia.

Morson says that Solzhenitsyn’s spiritual awakening began in a prison hospital when he heard of a prayer by U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt and mocked it as obvious hypocrisy. Another prisoner replied, “Why do you not admit the possibility that a political leader might sincerely believe in God?” Solzhenitsyn began to realize that atheism “had been planted in me from outside.”

He began to see the connection between conditions in the Soviet Union and its ideology of materialism and atheism. “If people are nothing but material objects,” summarizes Morson, “if there is nothing resembling what we call the soul, then concepts like ‘the sacredness of human life,’ ‘human dignity’ and ‘the inviolability of the person’ are merely bourgeois mystification.”

Instead, Communist ethics taught that the end always justifies the means, judging everything not in terms of some absolute principle but whether or not the result advances the cause of the Communist party. The notion that the ends justifies the means was absorbed even by the prisoners.

Prisoners who thought this way concluded that they would “survive at any price,” which meant “at the price of someone else.” Others might hesitate, but when party members were arrested, they were already prepared to betray others and, if they were intellectuals, to devise sufficient justification.

But the final stage for Solzhenitsyn in his conversion to Christianity was not his perception of other people’s evil, nor of the collective evil of the Soviet system, nor of the evil of Communist ideology. Rather, he had to face his own evil.

The final step to faith comes when you don’t simply blame “them” but realize your own sinfulness. Solzhenitsyn reflected on how, as an officer, he had looked down on ordinary soldiers and, even after he’d been arrested, made one of them carry his bags. Now, whenever he mentions the “heartlessness” and “cruelty” of his executioners, Solzhenitsyn writes, “I remember myself in my captain’s shoulder boards” and ask if he and those like him were any better.

Speaking with Solzhenitsyn after he’d undergone an operation, prison doctor Boris Kornfeld attributed his own Christian conversion to the recognition that no punishment is entirely undeserved. “It can have nothing to do with what we are guilty of in actual fact,” the doctor told him, “but if you go over your life with a fine-tooth comb and ponder it deeply,” you will identify a transgression for which you hadn’t paid the price.

Kornfeld was murdered within a few hours of this conversation. “There was something in Kornfeld’s last words that touched a sensitive chord, and that I accept quite completely for myself,” Solzhenitsyn wrote. “I had gone over and re-examined myself . . . why everything had happened to me. . . . And I would not have murmured even if all that punishment” were still greater.

The torturers may have escaped punishment, Solzhenitsyn concedes, but they “are departing downward from humanity,” while we, as compensation, experience an unexpected way to develop the soul. When Solzhenitsyn recognized the many ways he had contributed to the evil he saw, he found faith. “God of the universe! I believe again!” he wrote in a prison poem. “Though I renounced You, You were with me!”

Upon his release after eight years, Solzhenitsyn became a devout member of the Orthodox Church. But notice how his conviction by the Law led him to the Gospel.