Continued from yesterday.

Continued from yesterday.

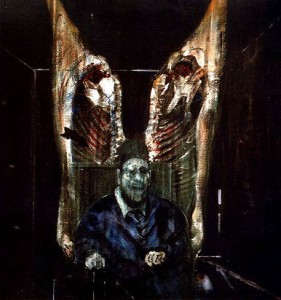

In retrospect, my reaction to Pope Francis’s election makes so much more sense when I consider that during my tenure at the college my artistic guiding lights were St. Francis and the painter Francis Bacon. About as far from a saint as one can imagine, Bacon is infamous for showing us things that perhaps we would rather not see: nightmarish self-portraits, unnerving studies of screaming popes, and writhing and wrestling biomorphic forms.

But Bacon was not interested in merely horrifying us. He was painting, as he said in an interview, to “excite himself”; spreading paint in a way that was expressive of his anger, his lust, and his love of painting. In a rare explanatory moment, he revealed to an interviewer that his numerous paintings that reference crucifixion were not religious but “an act of man’s behavior to another.”

Some moralists have said that his paintings are corrupting and harmful, but I’ve always felt that they do no more harm than if one took to hanging around a butcher shop or meat packing plant. To me, his paintings, like all great art, make us confront essential questions about the human condition.

My rather vague and unrefined view of Bacon was tested when, in 2004, at a conference at Notre Dame on the future of art in a Post-Christian world, I attended a keynote delivered by the eminent philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre titled “What Makes Religious Art Religious?” Using examples of paintings by El Greco and Mark Rothko, he made the claim that what makes a painting religious is not subject matter but when a “religious intention is communicated to the viewer.”

Over the course of about forty-five minutes, MacIntyre thoroughly supported his thesis, and then impressively fielded questions bent on picking apart his thesis for another thirty minutes.

During the Q & A segment, I asked what he thought of Francis Bacon’s use of the subject of crucifixion in some of his work. Bacon had been on my mind a lot that spring as I was drafting a chapter on the representations of violence in art, and I found myself returning again and again to his Figure with Meat, one of his numerous studies of Velasquez’s Pope Innocent X, picturing a screaming figure against a backdrop of sides of beef. MacIntyre without any hesitation answered, “I only talk about Francis Bacon in private,” drawing great guffaws from the crowd.

Dissatisfied and now very curious, I tracked down MacIntyre’s email and sent him a note asking for an appointment. He sent a very cordial email right back, and on the appointed day I went to his small and sparsely furnished office in an unflattering former dormitory building that had been turned into faculty offices.

When I asked about Bacon, he revealed, anti-climatically, that he held him in “high regard” and found him to be a “remarkable” painter. He said this, then sat back in his chair, folded his hands, looked wearily at me across his desk, and politely asked me what my interest was in Bacon. I told him about the book I was writing and how I was curious to what extent his work might have informed or impacted me—my way of thinking.

“I would never ask such a question,” he said curtly and then was silent. After a few mutually awkward moments, I thanked him, he wished me luck on my book, and I left, very confused.

I can only guess at what MacIntyre might have been driving at when he said he only talked about Bacon in private. Far be it from me to try to speculate on the thoughts of someone like MacIntyre, but perhaps Bacon’s paintings seem to him pornographic: depictions of people indisposed, in flagrante, in extremis, which places him in the uncomfortable position of having to contend with such subject matter in public.

As far as why he would never ask such a question, perhaps it is because he does not need a Francis Bacon painting to know that humans struggle to control their appetites, and that paintings such as Bacon’s aestheticize dissolution and make it, against all rationality, attractive.

In Dorothy Day’s autobiography The Long Loneliness she diagnoses this same problem in the young, idealistic, politically-minded workers so often attracted to the movement. They seem to so romanticize poverty and being in solidarity with the dissolute that they themselves become dissolute, more like those first Parisian bohemians who drank and cavorted as a protest against bourgeois values.

In the end, though, I am not Alasdair MacIntyre, and so I have continued for nearly ten years now to stubbornly ask what draws me to Bacon. It is, surprisingly, what also draws me to St. Francis—I don’t want to be Francis, but I like his style, his choice to allow the inside in all its brightness and darkness to leak out.

Though motivated by different impulses, St. Francis and Bacon were bursting with a desire to embrace the ugliness and spiritual poverty of this world in a way that called attention to it, named it, so that others might see.

David Griffith is the author of A Good War is Hard to Find: The Art of Violence in America (Soft Skull). He is the Director of Creative Writing at Interlochen Center for the Arts in Michigan where he lives with his wife, fellow Good Letters contributor Jessica Mesman Griffith, and children, Charlotte and Alexander. His essays and reviews have appeared in Image, Utne Reader, The Normal School and online at killingthebuddha.com. He blogs at Pyramid Scheme.

Art Pictured: Francis Bacon. Figure With Meat, 1954. 51.1 in × 48.0 in, Chicago Art Institute.