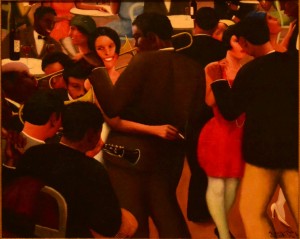

Archibald Motley’s most famous paintings jump and jive, then they wail. You might have seen Blues (1929) or Hot Rhythm (1961). There are a lot of people moving around on those two canvases.

Archibald Motley’s most famous paintings jump and jive, then they wail. You might have seen Blues (1929) or Hot Rhythm (1961). There are a lot of people moving around on those two canvases.

There is music. There are fabulous outfits. The word “commotion” comes to mind when you look at a painting by the mature Motley (a retrospective of his work is currently on display at LACMA in Los Angeles).

Motley studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. Later, he received a Guggenheim Grant to go to Paris. This was in the late 1920s. Looking at a painting like Hot Rhythm, you can see that Motley picked up lessons in composition by studying everyone from Rubens to Picasso.

Getting motion-filled bodies together in one painterly frame is not, it turns out, a particularly easy thing to do. Just take a minute to study the balancing sets of upraised arms and objects in Hot Rhythm—the dancing girls, the musicians, the instruments—and you start to get a sense of how deeply planned out this otherwise “wild scene” really is.

The point is, Motley knew how to paint. He also knew what he wanted to paint, which was black people. Archibald Motley was, himself, a black man, born in New Orleans in 1891.

Actually, his racial identity was rather more complicated. That’s true of many African Americans, no doubt, but it is especially true in New Orleans. Motley claimed African American, European, and Native American heritage. America being America, he was usually tagged a black man.

The nuances and confusions of racial identity made their way into many of Motley’s most powerful paintings. To whit: The Octoroon Girl (1925), a portrait of an elegant young lady who, in the American obsession with precise racial identification of the time, was relegated to the category of people with one-eighth African ancestry.

The Octoroon Girl makes me think of Hans Holbein’s portrait of Christina of Denmark. It’s something about the intensity of the eyes versus the delicacy of the hands.

Motley graduated from art school in 1918, setting himself up to be a major figure in what’s now called the Harlem Renaissance—though Motley did most of his work in Chicago.

In 1933, Motley made a painting called Self-Portrait (Myself at Work). Motley, in an “I’m an artist” get-up that includes a beret, painter’s smock, and palette, stares directly out at the viewer. But when we look to the left of the canvas, just off to Motley’s right side, we see he’s not looking at us; he is looking at the model he is painting. That model is a nude woman.

This creates the unusual scenario in which we, the viewers of the painting, must imagine ourselves to be the nude model that Motley is painting. This situation is not completely unprecedented, of course. Velasquez did roughly the same thing with his famous (and after Foucault, notorious) Las Meninas.

In Las Meninas, we are meant to imagine ourselves as the King and Queen of Spain. Archibald Motley is slightly less ambitious with his Self-Portrait. Who is this woman being painted, anyway? Is she merely a model? Is she one of the ladies of ambiguous racial background that we see in other paintings?

It is hard to say. The point simply seems to be that we can stand in her place, and she in ours. Velasquez created the scenario in Las Meninas, it is conjectured, mostly to show the complicated layers with which paintings represent “reality.”

Motley’s point is a little bit different, I think. It is to use the medium of painting to get us mixed up with one another, mutually implicated. There’s a further key in the painting that points us in this direction. Hanging on the wall behind Mr. Motley, just off center but impossible to miss, is a crucifix.

Archibald Motley—like many African American-Native American-Europeans from New Orleans —was a devout Catholic. Motley’s Self-Portrait suggests that what holds everybody—the painter, the model, and the viewer—in the painting together is the Cross.

The crucifix isn’t just an incidental object in the painting. It isn’t just there. It hovers meaningfully over the scene in which Motley stares at us and we stare at him. The painting is a painting that, like Las Meninas, is also about painting. So, the act of painting, for Motley, and the meaning of the crucifix are deeply related.

Motley’s self-portrait is self-consciously about his own belonging and the belonging of all the racially mixed-up brothers and sisters that he was out there painting day after day. “How do I get all these people into the frame?” Motley seems to be asking. “How do I get them represented? How do I get them into the story?”

The answer is to do just that: to get everybody in the painting; to make painting big enough for all the ambiguities; to show all the wild scenes in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago during the Jazz Age; to make portraits of the Quadroons and the Octoroons, and the Quintroons, too.

There’s a now famous phrase in James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. The phrase is “here comes everybody,” which is a reference to the catholicity, the universality of the Church. Here Comes Everybody is also a play on the name of one of Finnegan’s Wake’s main characters Haroun Childeric Eggeberth, who has so many names and identities in Finnegan’s Wake, that he might as well be one of Motley’s Octoroons.

In an essay about Joyce’s book, Anthony Burgess wrote:

As long as the race exists, Finnegan’s Wake will remain one of its big pertinent codices. The corpse is “cropse.” Or, to borrow Eliot’s borrowing, “Sin is behovely, but all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” This is not the philosophy of Shaun, the vapid liberal demagogue, but the faith of HCE, who—”Here Comes Everybody”—is suffering man himself.

The crucifix was the key to painting as Motley envisioned it because only the crucifix has the room truly to let everybody in. Come ye, sinner, come on in to the great and infinite codex.

What gave Motley the faith that he could get everyone inside painting is that he knew everyone was already in there. So, he painted tons of pictures packed full of everyone. They kept coming, and he kept painting.

Morgan Meis is the critic-at-large for The Smart Set (thesmartset.com). He has a PhD in Philosophy and has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, and The Virginia Quarterly Review. He won the Whiting Award in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. He can be reached at [email protected].

The image above is titled “Blues” and is painted by Archibald Motley, found under ptwo, used through Creative Commons License.