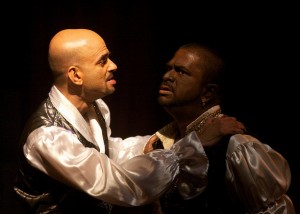

Seeing a fine production of Othello recently has got me thinking about the art of evil, a fitting topic for Lent. And, yes, that pun in “art” is intended.The creativity of Iago’s evil machinations is the force driving Othello’s plot; and art in general—in all its genres—often portrays how evil works in our world.

Seeing a fine production of Othello recently has got me thinking about the art of evil, a fitting topic for Lent. And, yes, that pun in “art” is intended.The creativity of Iago’s evil machinations is the force driving Othello’s plot; and art in general—in all its genres—often portrays how evil works in our world.

I hadn’t seen or read Othello in decades, and I’d forgotten how much it is Iago’s play.

Not only is he the primary character for the first half of the play: the one with the most lines and the one whose absolutely evil essence is the play’s focus. He’s also, in a sense, scripting the entire play: he sets up the scenes where characters act out his bidding; he puts the idea of Desdemona’s infidelity in Othello’s mind and craftily whips Othello into a frenzy of jealousy; he even scripts the manner of Desdemona’s death (“strangle her in bed” he says point blank to Othello in IV, 1).

In fact, Othello only becomes a truly Shakespearean character—one speaking dense, luscious language—after Iago has deliberately transformed him into obsessive jealousy personified.

Watching Iago at work, I was terrified by the ways that evil can get a stranglehold on us. In fact, I think this was Shakespeare’s own interest in the play: not Othello’s jealousy but rather the power of evil to turn us into monsters who destroy one another and ourselves.

So I found myself wondering: Where is Iago at work in our own world today?

I don’t think it’s mainly in individuals. Yes, there are some evil dictators around the world. Yes, there is ISIS. And yes, I’m often tempted to label as evil some of our own politicians and media personalities, whose policies and pronouncements I find terrifyingly destructive of the collective wellbeing.

But the “art of darkness” (to play on Hardy’s title) is practiced today on a grander scale, I think, and all the more insidious because it’s not concentrated in a single person.

The enormous systems of injustice that keep whole classes and even populations in poverty and oppression; the greed that seems the driving force of the multi-national corporate power structure; the racism and demonization of the “other” who is different from ourselves; war itself, I’d even add. These are all much slipperier than Iago’s evil, harder to get a grip on, in our minds and in our art.

Do we have an art of evil that portrays the workings of these huge systemic horrors? I guess the modern locus classicus would be Harper Lee’s 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird, with its gripping dramatization of the deadly mechanics of scapegoating.

Not long ago, I re-watched the magnificent 1962 film version and was struck by how literally dark the whole movie is. Over half of its scenes take place at night, in a menacing manner made especially effective by the black-and-white camera work.

Earlier in the century there was Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, also a masterful portrayal of systemic evil at its nasty work of grinding up the poor (as I wrote about in a previous post).

But what about paintings, music, poetry?

I think of Auden’s verse, especially his sequence Horae Canonicae, with its condemnation of our collective indifference to the suffering of others. I think of Rouault, of the dignity he gives to the marginalized like prostitutes and clowns, and his subtle way of implicating us all in their victimization.

For contemporary visual artists, the collection A Broken Beauty, edited by Theodore Prescott, includes some extraordinary works that grapple with the scary grip of evil forces. The great French composer Messiaen gave us some of the sounds of absolute evil in his “Quartet for the End of Time,” composed while he was a prisoner of war during World War II.

And there’s no more powerful assemblage of worldwide recent poetry meditating on systemic evil than Carolyn Forché’s anthology Against Forgetting.

And the effect of all this art portraying evil? I’m sent to my knees praying the close of the Lord’s Prayer: “deliver us from evil.”

Systemic evil seems overwhelming. I’m afraid I have to concur with Reinhold Niebuhr in his classic analysis Moral Man and Immoral Society—that, “tragically” (Niebuhr’s term), we will always have systemic evil with us.

Yet I don’t believe that God wants us simply to roll over and let systemic evil have its destructive way. Here again, the arts come to our aid. These very arts portraying evil’s force also enact our hope. I once heard Elie Weisel say that “every act of creativity is a defiance of evil.”

Creativity is an act, an action, a “yes” to the forces of good. And all our individual or group activities in defiance of evil are creativity at work as well. But to engage in these activities, I need the pep talk that Denise Levertov gave herself at the end of her poem “Writing in the Dark”:

Keep writing in the dark:

a record of the night, or

words that pulled you from depths of unknowing…

or opened

as flowers of a tree that blooms

only once in a lifetime:

words that may have the power

to make the sun rise again.

Like words, our actions against the dark “may have the power to make the sun rise again.” Or they may not.

Yet, as the hero Atticus says in To Kill a Mockingbird: you stand up against evil because it’s the right thing to do, not necessarily because you’ll win out over it. This is the art of living aright.

Peggy Rosenthal is director of Poetry Retreats and writes widely on poetry as a spiritual resource. Her books include Praying through Poetry: Hope for Violent Times (Franciscan Media), and The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford). See Amazon for full list. She also teaches an online course, “Poetry as a Spiritual Practice,” through Image’s Glen Online program.

Picture above credited to Shehal Joseph and used under a Creative Commons license.