As France, and indeed Europe, is left to unpack the horrific murders of nearly a dozen cartoonists and policemen at the office of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, and 4 Jewish shoppers at a Kosher grocery store, I find myself across the pond thinking about the relationship between freedom of speech and notions of the sacred in popular Western discourse. The magazine was notorious in France for it’s unapologetic satire; it’s most controversial pieces often published racist and pornographic caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad to poke fun at Muslim notions of sacrilege. On Friday, the violent conclusions of dual hostage situations ended both the 2-day manhunt for the pair of French-born brothers and the stand-off in a Jewish deli where nearly two dozen people were held hostage by the brothers’ associate.

As France, and indeed Europe, is left to unpack the horrific murders of nearly a dozen cartoonists and policemen at the office of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, and 4 Jewish shoppers at a Kosher grocery store, I find myself across the pond thinking about the relationship between freedom of speech and notions of the sacred in popular Western discourse. The magazine was notorious in France for it’s unapologetic satire; it’s most controversial pieces often published racist and pornographic caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad to poke fun at Muslim notions of sacrilege. On Friday, the violent conclusions of dual hostage situations ended both the 2-day manhunt for the pair of French-born brothers and the stand-off in a Jewish deli where nearly two dozen people were held hostage by the brothers’ associate.

Though the concept of individual freedom is one which finds global resonance (demonstrated in the recent uprisings – failed and otherwise – in the Middle East), it is often seen as a particularly salient point of commonality among Western cultures. In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, we were constantly told that an amorphous “they” hate us for “our” freedoms. The assumption after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, is that the Kouachi brothers attacked the magazine because it dared to uphold the ideals of freedom of expression by poking fun at politicians, religious fundamentalists and the very concept of sacredness.

The idea that the Western world is linked by our common values regarding freedom of expression has been often repeated. The French revolutionary motto, Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, has inspired millions since 1790 – including in former French colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. Most Western countries hold the idea of individual freedom as their defining national characteristic.

Liberté

When I first learned about the Charlie Hebdo massacre, I immediately thought of my uncle. For many years he penned satirical poetry in a magazine and performed in a SNL-type comedy troupe. He and his colleagues poked fun at a corrupt political elite who ruled a theocratic military dictatorship and for their searing skits, his troupe faced constant censorship and were ultimately taken off the airwaves. Other members of my family have lived in self-exile for decades for their political views. Freedom of speech is sacred to me.

Like my uncle and his colleagues, the staff at Charlie Hebdo often mocked their political, intellectual and economic elites. Unlike my uncle, they often “punched down” and mocked Muslims by deliberately insulting Islam and the Prophet Muhammad PBUH. The magazine constantly mocked the beliefs of millions of French citizens – citizens whose origins are from the countries that France colonized in the 19th and 20th centuries, and who today still face enormous barriers to upward mobilization including equal access to education, housing and jobs. This is not to say that my religious tropes must be sacred to everyone else. Indeed, my religious freedom is protected when society elevates the right to freedom of speech and expression.

Freedom of speech, freedom of expression, and freedom of thought are globally salient values. People in all corners of the world want to express themselves without fear of censorship, arrest, or murder. These are not really Western values, inasmuch as they are human values. Reasonable people might disagree about what ought to be said in polite society and this is where robust, respectful national discourse is critical. Where does society draw the line between freedom of speech and incitement to hatred? Should society draw a line between freedom of speech and incitement to hatred? Important questions, but in the end, reasonable people must also agree that mocking even a sacred trope should not be met with violence. Fundamentalists of all backgrounds have the right to express themselves – but with words, clothing and cartoons, not bombs and bullets.

Egalité

The first time I realized that the US and France have differing viewpoints regarding religion and freedom of expression was when I was a child and heard about two sisters who were suspended from school because they refused to remove their hijabs. I realized from these incidents, collectively known as l’affair du foulard, that unlike the US, France sometimes bans some of it’s own citizens from wearing a headscarf in public.

How do the rights and responsibilities of citizenship relate to national culture in pluralist democracies? Though our own revolution was heavily influenced by the French, there are nuanced differences between the US and French view on individual liberties. Both nations are proudly secular, but while US law and societal norms ensure individual citizens have the right to enjoy both freedom of and from religion, the contemporary French laïque system focuses on individual citizens’ right to freedom of thought, which is typically manifested by freedom from religion in public.

Practically, French laïcité is enforced by the religious neutrality of public servants in public services. Students are not allowed to wear headscarves in public schools and public servants are not allowed to wear headscarves while at work. Religious expression is expected to be “discreet” and is often not welcome in public, which has led to a ban on women appearing in public in a full face veil, on the grounds of promoting public order and human dignity. The application of French law upholds the cultural norm that that society’s freedom from religion trumps an individual citizen’s freedom of religion.

It’s a tricky line to negotiate – whose rights must be protected at which cost? Much has been made of Charlie Hebdo‘s firing of a cartoonist was accused of anti-Semitism in 2009; many argue that the paper’s decision proves that anti-Semitic satire is deemed unacceptable, while Islamophobic satire is welcome. But there is a difference between the responsibility of a democratic government to uphold freedom of speech and the right of private publication to freedom of speech – abhorrent, racist and hypocritical as they may be.

This issue was underscored in the summer of 2014, when France banned pro-Palestine rallies in an attempt to prevent anti-Semitic violence against synagogues and Jewish areas. It should go without saying that the rise of anti-Semitic violence in France is reprehensible and unacceptable. But instead of denying citizens their right to express their views, the state might have considered increasing police protection in Jewish areas and working with Muslim leaders to promote peaceful protests and cracking down on violent offenders.

As the daughter of African Muslim immigrants to the US, I have long known that democratic systems don’t automatically erase societal racism and the marginalization of minorities. But I also know that all citizens are supposed be equal under the law.

Fraternité

The deaths of the Kaouachi brothers will not give us any clear answers as to their motives, but that won’t stop pundits on both sides of the Atlantic from continuing to claim that because Muslims are offended by pornographic portrayals of our prophet, Islam is inherently incompatible with freedom of speech. These pundits argue that Western Muslims should be considered as a potential dangerous fifth column by society, political leaders, and national security apparatuses.

As a citizen of a democracy where my religious freedoms are protected, I fully defend the rights of anyone who wants to mock my religion and all that I hold sacred, but I shouldn’t be told that I have to like their mockery in order to be a model citizen. France is full of Muslims who are law-abiding citizens, living in and contributing to a society that has not yet honestly grappled with the historical legacy of colonialism. Despite this, as the French academic Olivier Roy wrote, there are more French Muslims working for French security than for Al-Qaeda.

Europe on the whole is grappling with questions of national identity. What does it mean when half of your national football team is of immigrant origin? How can secularism best be implemented in religiously diverse societies? How does a region whose laws are based on promoting individual liberties extend those rights to citizens of different religious and cultural backgrounds without losing those very values in the process?

The Charlie Hebdo attack in France occurred on the heels of massive anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rallies and pro-tolerance counter rallies in Germany. Both types of demonstrations are rightfully protected under free speech laws and generated a robust debate in Germany about national identity. Further north, Sweden has seen a rash of violent anti-Muslim attacks in the form of bombs and arson in several mosques across the country in recent weeks. The Swedish response to these attacks has been unequivocal: police are investigating these attacks as crimes and the Swedish public is reiterating their commitment to pluralism by “love bombing” mosques.

In the aftermath of the attacks, there have been over 50 recorded incidents of anti-Muslim violence in the last week alone and the government has mobilized thousands of troops to protect high-risk potential targets. However, French civil society has largely responded to the violence with messages of unity. Millions of French citizens attended a solidarity rally in Paris on Sunday. The brother of a Muslim police officer slain outside the Charlie Hebdo office made an appeal for people to not confuse Islam with terrorists at a press conference. French Jews and Muslims are united in their condemnations of terrorism.

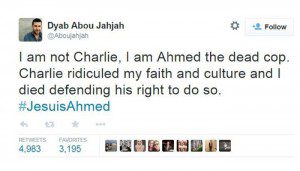

Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité. There’s a reason this powerful slogan has endured for centuries and inspired revolutionaries the world over. Liberté promises that I have the right to publicly express my views. Égalité promises that my fellow citizen has an equal right to publicly express her views. Fraternité exhorts us to work toward the common good with mutual respect. As France, and indeed Europe, begins to unpack these horrific events, it has become clear that a new conversation is beginning to emerge. The purveyors of hate, whether political right-wingers or religious fundamentalists, are vigorously challenged. The solidarity hashtag #JeSuisCharlie led to a layered and more complex conversation about protecting freedom of speech with the emergence of #JeSuisAhmed. I hope that public discourse around national identity, the sacred secular values of freedom of speech, and the rights of citizens of all backgrounds will continue to be nuanced. And for a country that has long struggled with integrating it’s former colonial subjects, that would be a huge a step in the right direction.