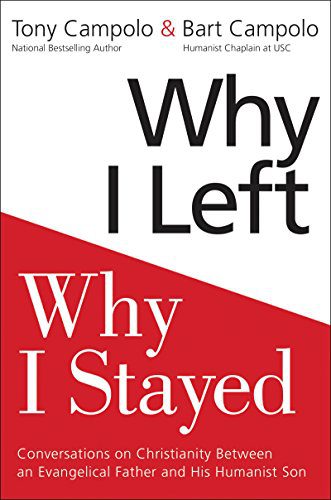

Tony Campolo is one of the most gracious and well-spoken voices that I know of within Evangelicalism. For years, he has focussed his ministry on living out the “red letters” of Jesus. And for years, his son, Bart Campolo, took part in this ministry with him. But that all changed when Bart realized he no longer believed in God.

In Why I Left, Why I Stayed, Tony and Bart discuss their diverging journeys, their now-differing beliefs, and their still-shared convictions. I can hardly imagine two people better qualified to have this conversation in a way that is mutually dignifying, while still probing into the difficult questions that must be asked. And their book does not disappoint.

I have to admit that one of my strongest emotions while reading was one of jealousy. I wish I had the option to carry out such conversations with my family in the grace-filled manner here exemplified. While Bart’s journey has taken him outside of Christianity, my own has simply shifted me from the Calvinistic fundamentalism of my upbringing to a Christian faith that is more progressive, more ecumenical, and more soundly rooted in historic orthodoxy.

Yet this shift has cost me the relationship I once had with my parents and extended family. It stings for me to read how “Tony’s God-consciousness kept him from saying any hurtful words … and that it keeps Tony from replying with bitterness” (p. xv), when the experience with my relations has been so far opposite. Nonetheless, this book is important for precisely that reason. We need to see these conversations modeled in a better way.

It is refreshing to see the honesty from both sides, acknowledging that the views they hold are based more on feeling than facts.

From Tony:

I’m still a fairly good Christian apologist, but at the end of the day, I have to admit that the primary foundation of my faith is not what I know, but rather what I feel. …

I can’t remember when I did not accept the basic doctrines of the Christian faith, …. (p. 31)

And from Bart:

In my case, however, all that really matters is that over many years my ability to believe in any kind of supernatural reality gradually faded away, until I finally became convinced that the natural universe—matter, energy, and time—is all that exists. …

I didn’t choose not to believe in God; I just stopped believing. … Slowly but surely, that benevolent presence that once seemed absolutely real to me felt like an imaginary friend instead. (pp. 43–44)

But that isn’t to say that nothing more concrete plays into it. For Bart, beyond a general disbelief in the supernatural, he came to view certain elements of his father’s faith as simply unacceptable and even immoral, namely, original sin and penal substitutionary atonement.

Original sin is where the Gospel starts, isn’t it? … We are all sinful by nature, and therefore utterly incapable of redeeming ourselves and entirely deserving of eternal damnation. …

This may well be my biggest problem with evangelical Christianity: It is grounded in a bizarre, counterintuitive self-hatred that claims we have no intrinsic goodness or value of our own, but rather deserve to be eternally punished simply for being born human. Indeed, according to the “good news,” our only hope is the unmerited favor of God, which comes to us in the form of Jesus, the sacrificial lamb who suffers and dies in our place. …

Why can’t our gracious God simply forgive us, the same way Jesus taught his disciples to forgive one another? … How could slaughtering an innocent make the guilty party any more fit for divine fellowship? Parental discipline I can easily accept, but not the retributive violence of the Cross. To me, that is what’s really immoral. (pp. 93–95)

I’m actually in full agreement with Bart’s objections here. The idea of original sin is “bizarre” and “counterintuitive.” It does not accurately reflect the human condition, which is certainly flawed, but not totally depraved. And the idea that God would punish Jesus instead of us is about as immoral as it could be. God does not need a sacrifice. Indeed, God does “simply forgive us, the same way Jesus taught his disciples to forgive one another.” God’s discipline of his children is always and only parental—it is restorative, not retributive.

The notion of original sin and the retributive view of the cross are both inventions of Western Christianity. They find their origin in men like Augustine, Anselm, and Calvin, not Jesus or the Apostles. The Eastern branch of Christianity, for the entirety of its existence, has rejected these ideas. And more and more Western Christians (myself included) are coming to reject these ideas as well, restoring our theology to the more ancient faith once delivered.

I’m somewhat surprised, given what I know of him, that Tony Campolo is still holding on to these beliefs. But as progressive as he may be in many areas, this is one area in which he remains quite a bit more conservative. He critiques leaders of the emerging church and others for speaking along the same lines as his son, and he offers his own solution:

My response to such leaders has been to point out that the penal substitutionary doctrine of the atonement is only one explanation of how our salvation was accomplished by Jesus on the cross, and to remind them that none of them alone can contain the whole story. What happened at Calvary is far too profound to be reduced to a simple formula. I do not reject penal substitutionary atonement out of hand, but I don’t put all my theological eggs in that basket, either. The glory of our salvation is bigger than that. (p. 97)

On the one hand, I completely agree that no one theory of atonement can capture everything that happened. As just a few quick examples, the recapitulation, Christus victor, moral influence, and mimetic views of atonement (among many others) all point to elements of truth, and we are better off using all of them together than any one of them on its own. However, unlike these other views of atonement, penal substitution does not in any way point us to the truth. It actually points us away from the truth that God is love and that his forgiveness is unconditional. I don’t believe it has any legitimate place within Christian theology, and I think it should indeed be rejected out of hand.

But I don’t mean to be too harsh on Tony. His overall understanding of the Christian message is so much better than the majority of Evangelicalism. For example, he shared some of his views by recounting an interaction he had with his students years ago. Here are a few snippets to gain a better idea of what Tony is all about:

“Look,” I resumed, “as I was listening to you list the traits of humanness, something kept telling me that you were also describing what God is like. God is all the things that you are telling me you want to be. Then it hit me—humanness and Godness are one and the same. You want to be everything that Jesus was and is. What you call being human is really being Christlike.” …

One of my students said, “If Godness is humanness and vice versa, then we need a new way of talking about Jesus. Jesus is God because He is fully human, not in spite of His humanness. When I was a kid growing up in Sunday school, it seemed weird to me that God could be a man, but if I follow what you are saying, it is the most logical thing in the world. Jesus was God because He was fully human and He is fully human because He was God. In Jesus, everything that God is was revealed and everything that a human being is supposed to be was realized, and both of these were one and the same. …”

“That’s right,” I chimed in. “Each of the rest of us is still in the process of becoming human. Only Jesus is the fullness of what we aspire to become. …” …

“To be saved from sin is to be delivered from this and every other kind of alienation. Is is to enter into a personal relationship with the ultimate human, being transformed into His likeness to enjoy the ecstasy of full aliveness.” (pp. 80–83)

Now this is the kind of Christianity I believe. This is faith of the early church. This is theosis—the idea that “the Son of God became man so that we might become God,” as Athanasius so famously put it in his On the Incarnation.

Returning to Bart, if he no longer believes in God, what does he believe in these days? In a word, love. More specifically, Bart’s purpose is “living a life of love” (p. 64). He grounds his morality in the Golden Rule, which he sees as coming from the shared traditions of humanity, rather than from Jesus in particular (p. 105, a debatable claim, but one I won’t press at the moment). So Bart’s moral center would seem to remain the same as Christianity, even if he thinks these concepts originated elsewhere. Christian morality has never been about following a list of dos and don’ts, but about living a life of love, based on the Golden Rule.

Why, then, does he reject Christianity? Is it because of the objectionable elements considered earlier? Surely not. I can’t believe that one as well-read as Bart is unaware of the immense Christian tradition that agrees with him in rejecting these things. Per my reading of his words, it seems like Bart’s rejection of Christianity really boils down to one thing: he can no longer believe in the supernatural.

At the same time, I can’t help but think that Bart remains in some ways more Christian than many who still identify as such. The First Epistle of John makes it clear that “love is from God, and everyone who loves is born from God and knows God,” and furthermore, “God is love, and those who remain in love remain in God and God remains in them” (1 John 4:7, 16, CEB). If Bart is continuing to live a life of love based on Jesus’ Golden Rule (and I see no reason to doubt the sincerity of Bart’s love), then John’s words appear fairly straightforward. Bart remains in God, and God remains in Bart. Though Bart may, for now, have lost his ability to believe in God, God still believes in Bart.

As I wrap up my review, I want to emphasize again what a refreshing read this was. Both Tony and Bart shine in their humility toward one another, and they have left us an exemplary model for working through these difficult matters with those who are closest to us. I’ll end with one more quote, from their joint conclusion.

As we said at the beginning, while we come to it differently, each of us always reaches the same conclusion about this life: Love is the most excellent way. Moreover, each of us is both sure and content that the other has found that way. For now, at least, that is enough. (p. 158)

Pick up your own copy of Why I Left, Why I Stayed as a hardcover or a Kindle eBook.

Disclosure: I received a free copy of this book from HarperOne in exchange for an honest review.