Over at The Week, I wrote a post arguing that most Christians will continue to believe that same-sex marriage is wrong, because sexual complementarity is an important part of the faith. My view was not to advocate for a particular position, but rather to argue for pacifying by seeking to explain why most Christians wouldn’t give up on it.

I just want to point to a couple fair-minded and intelligent responses, and say a few things in response to them–again, more in a spirit of explication than one of argumentation.

The first comes from “Letters to the Catholic Right“, starts with bouncing off of idiosyncratic gay Catholic writer Richard Rodriguez’s rendering of Christianity as a “desert religion.”

Because Christianity has its roots as a desert religion, it was deeply patriarchal, and therefore heteronormative. Thus, the implication seems to be, now that Christianity is no longer in the desert, it doesn’t have to be “patriarchal.”

I find Rodriguez’s perspective fascinating, and I think there’s a lot to be drawn from his analysis of Christianity’s “desert origins.” I would say a couple things, here, though.

The first would be that, if one is a Christian and one therefore believes that the God who created the Universe chose to form a people after himself in preparation for His revelation in Jesus Christ, this “desert-ness” cannot be viewed as some historical coincidence that can be written off once it becomes inconvenient, but rather as an integral part of God’s providential act of self-revelation.

The second would be that, indeed, Christianity hasn’t been a desert religion for a while, and arguably never was. By which I mean, while Christianity incorporated its Jewish/desert roots, it also substantially reworked and redefined them around the revelation of Jesus as the Messiah. I don’t think it holds water to say that Christianity just reincorporated Jewish morality, which itself is just “desert-people” morality. The obvious examples are polygamy and divorce–institutions that one easily sees as integral to a desert/patriarchal moral worldview, and that Christianity nonetheless rejected. N.T. Wright has very convincingly argued that Paul’s entire theological enterprise was a redefinition of Judaism around Jesus and the events of his life. What this “cashes out as” in terms of specifics is that some aspects of Jewish morality were kept, and others, not. Polygamy–out. Heteronormativity–in.

So just saying “Christianity was originally a desert religion, and therefore . . .” seems to me to oversimplify things quite too much.

The other argument is that God’s Fatherhood is just a metaphor, and therefore doesn’t have implications for how we view the sexes.

Now, first of all, I believe that in technical theological language, that’s just not true. As I understand, theological language distinguishes between metaphor and analogy. The rough idea is that, yes, God is passing all understanding, but God has revealed to us some of His aspects that truly apply to Him, insofar as we can understand them. So, for example, talk of the Holy Spirit as “wind” or “fire” is a metaphor: there’s nothing intrinsic about the Holy Spirit that is like “wind” or “fire.” By contrast, talk of God as Father is an analogy: God actually is a “father”–even though this fatherhood is quite unlike human fatherhood.

And second of all, I kinda want to appeal to the refutation of Bishop Berkeley’s immaterialism. The language of the fatherhood of God is absolutely central to the Christian Scriptures, the Christian Creed, the Christian experience (as Paul says, it is the Spirit that makes us cry out “Abba! Father!”). Is it really warranted to view it as “just a metaphor” that doesn’t teach us anything about what fatherhood means on Earth and what the sexes were created for?

Frankly, personally, if I was a Platonist reasoning myself from first principles to a Creator One in whom all Good, Beauty and Truth converge, I would be more inclined to believe that this One is a Mother, given what seems to me to be the fundamental sheer givenness of existence. (My hobby is inventing neoplatonist cults.) But this is not how the Biblical God has chosen to reveal himself to us. And reflecting on the data of revelation, Christian Tradition has always (and, it seems to me, unimpeachably) held that God’s fatherhood is not simply a metaphor that could be costlessly replaced by some other one, but rather a reality, albeit one which our own words convey only partially.

Moving on:

Then, too, look at the metaphors the Church uses to teach about marriage, gender, and the nature of God. That’s a big ol’ Gordian knot, and no one on earth is undoing it. Consider: the Church is the Bride of Christ, but men have to lead it because they have to stand in persona Christi, even though those men are sometimes referred to as “wedded to God,” who by the way has to be male because we call him Father, but gay marriage can never be allowed because a male can never be married to a male…

Now, I want to first emphasize the element of truth that there is to this discourse, which is that it’s unquestionable that divine revelation relativizes gender, and in particular, gender roles. In Christ, there is no male and female… It is in my view indefensible to claim that “Christian sexual morality” or “Christian gender roles” or whatever shake down to “the morality of middle class white America circa 1955” or something. How else do we account for Joan of Arc, Blanche of Castille, Teresa of Avila, Hildegard von Bingen, Maria Montessori, Adrienne von Speyr, and countless other fearless and boundary-challenging women saints?

With that being said, and well and truly said, it still seems to me that it’s impossible to do justice to the witness of Biblical revelation and Church Tradition without taking into account the many, many, many ways in which it talks about the two genders as being ordained by God, and complementary, and this complementarity as being an important part of God’s creation plan for humanity’s flourishing.

It’s the classic Catholic both/and, and wrestling with both/ands is hard–but valuable. There is always an element of mystery, of groping in the dark, but taking a shortcut by simply jettisoning one side of the equation simply will not do.

Now I move on to the response by my friend Conor Friedersdorf, who is agnostic and generally libertarian, and whose libertarianism causes him to support both civil same-sex marriage and the rights of religious communities to dissent from progressive orthodoxy. Conor is one of the most fair-minded and intelligent writers around, and it’s always a pleasure to talk with him. Conor remains unconvinced that heteronormativity remains essential to the Christian message and still believes that Christians will come around to share this view.

Unfortunately, Conor loads the dice from the start:

My suspicion is that regarding homosexuality as sinful will prove no more integral to Catholicism than did, for example, believing earth was at the center of the universe.

The difference, of course, is that geocentrism was never a doctrine of Christianity. This is a perfect example of the false historical premise that I was talking about. If you buy that sort of narrative, then of course seeing Christianity’s heteronormativity as expendable will come easy, but this is just a category error, and shows to me why I was right to write that piece.

(Yes, many Christians believed in geocentrism but, to be ever-so-slightly provocative, it was for the same reason why most Christians today believe in the theory of evolution: because it was the scientific consensus. This is how science works: old paradigms die hard, and are only fitfully overturned. Einstein’s famous phrase “God does not play dice with the Universe” was spoken to mock the concept of quantum mechanics. Then as more evidence came in, Einstein changed his mind. Was Einstein a religious obscurantist? I heartily recommend to Conor the book Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion.)

(For the record, I am a theist who believes in the historical Jesus and the wisdom of many of his teachings. I am agnostic about most religious questions.)

As an aside, I find this absolutely fascinating. What you might call “agnostic theism” used to be a frequent position but is now quite rare, and I’m very curious to know more about Conor’s religious views. I would very much love to see Conor review D.B. Hart’s The Experience of God and N.T. Wright’s The Resurrection of the Son of God.

He writes:

The story Christians have been telling for 2,000 years goes something like this: The God who made the Universe is also, by his very nature, Love, and he made human beings with a very lofty vocation. Humans are meant to reflect His glory in the world; to be like God, that is to say, to be lovers and creators. Everything in the Universe has been put here to be used by God’s children to reflect his loving glory—and to teach them about God’s love.

While I fail to see how lizards that went extinct before the dawn of man, bubonic plague, and the smallest rocks on Mars were put here in the Universe “to be used by God’s children,” it seems to me that a Christian can believe every word in the above passage and embrace gay marriage.

A couple points.

First, yes, Christians can read the passage and embrace gay marriage—which is why the passage continues. 🙂

Second, just because Conor doesn’t see how dinosaurs and Martian rocks are there to glorify God doesn’t mean it’s not true. In particular, if humanity becomes a spacefaring civilization, as I deeply hope, we will find some God-glorifying use for those Martian rocks. (Also, hello, Jurassic Park???)

Just as platonic friendships can be said to reflect God’s glory (insofar as they involve humans who love one another) even though they’re in no way procreative, so too with romantic, same-sex relationships.

Well, sure. The whole argument is is that heterosexual love reflects God’s glory in a special way, a special way which in turn is a key to understanding what our sexual faculties are intended for, which in turn implies that some uses of those sexual faculties do not accord with God’s design. That may be wrong, but that’s the argument. To say that other forms of love also reflect God’s glory misses the point—of course they do.

Conor goes on:

Even accepting, for the sake of argument, that procreative sexual acts between men and women are particularly reflective of God’s glory, that does not logically imply that non-procreative sexual acts—acts less reflective of God’s glory, in this framework—could not also reflect God’s glory, even if less fully. Catholics manage to believe that consuming the Eucharist (as at the Last Supper) fosters a unique union with God without concluding that consuming normal bread or wine is sinful, or that gathering with friends for a casual meal is verboten.

Firstly, the argument is that God gave us our sexual faculties for a specific purpose. That does actually logically imply that using these faculties outside of what they were meant for is to go against God’s will.

Secondly, Conor’s analogy about the Eucharist is actually quite on point: for the Eucharist is not just “a meal”, but an act of divine worship, and that does very clearly preclude other acts of divine worship. The analogy, then, would not be between receiving the Eucharist and a meal between friends but, say, receiving the Eucharist and praying at a mosque.

This is not an unknown question for Christianity. In the syncretistic and polytheistic Greco-Roman world, it was not clear to all of the early Christians whether they could continue to worship at Pagan temples. The apostle Paul, in writings that Christians view as authoritative, warns them off in strong language—not, he hastens to add, that he is under any illusion that the Pagan gods are real, but because worship of the Christian God precludes idolatry. Indeed, in the Biblical narrative, pagan idolatry is insistently described in terms of the adultery of Israel/the Church against her faithful husband, God the Father (in contrast, the Book of Revelation describes Jesus’ triumphant return on Earth in terms of a wedding banquet). Among many other factors, this repeated motif is an important reason why Christians (and Jews) have always believed that God seriously cares what we do with our sexual faculties—that they have a spiritual, even eschatological dimension. And even to this day, Christians may not participate in non-Christian religious rituals (though they may, in exceptional circumstances, attend).

Now, Conor may not see why worship of the Christian God logically precludes the worship of other divinities. The frustrated Christian might respond that the God Christians worship says it does.

Conor goes on to object to my exposition of the Christian doctrine that marital complementarity and fruitfulness is meant to image the Trinitarian life:

Arguments of this sort have long been particularly unpersuasive to me. Even assuming a belief in a Holy Trinity, it seems strange to imagine that humans understand the Holy Spirit so well as to identify sound analogues to it; arbitrary to assume that God intends the relationship among Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to be the model for all sexual relationships; and (even assuming the Holy Trinity ought to be our model) questionable at best to declare that the relationship between man and woman reflects or parallels the complementarity of the Trinity. Let’s look closely at that last claim.

As a participant in the thought-provoking comment thread at Dreher’s blog put it, “So, the ideal marriage involves a member of each of the three sexes? Actually, since we tend to refer to all the persons of the Trinity as male, wouldn’t the proper analogy be a gay threesome? I’m only kind of joking, but this is to point out that you can do anything with analogies.” Quite so. I could craft a dozen human-relationship iterations with plausible parallels to the structure of the Trinity. No Christian, looking upon my frames, would take the parallelism as persuasive evidence that my made-up notions of Godlike relationships are the one true way. If Christians want to point to tradition or biblical passages about homosexuality as the basis for their believe that it is sinful, I understand, however much I might disagree. What I have never understood is why some Christians find the metaphor-based arguments persuasive, let alone conclusive.

On one level, this is a fair question to ask. On another, it is deeply silly. Why do Christians believe that heterosexual love reflects God’s image in a way that, say, gay threesomes don’t? Because the Bible says the former over and over and over again and the latter never.

Yes, you can do anything with analogies, but some analogies work better than others, and some analogies are stubbornly repeated by the Biblical narrative and others aren’t, and some analogies have been stubbornly held onto by Christians for 2,000 years and others haven’t.

For example, the Genesis poem portrays the creation of the world in terms of pairs of things that are meant to reflect God’s glory by working together holistically, culminating with the man-woman pair. Christians have understood the verse Gn 1:27, “God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” to mean that it is man and woman together who are (in a special way, at least) the image of God in humanity and, in turn, it has been thought that this divine decision reflects the fact of the Trinity as a union of persons. Christians view these Genesis passages as important not for abstruse historical reasons, but because both Jesus and Paul explicitly call attention to them (Matt 19:4-6, Eph 5:31), as offering a key to the mystery of marriage. The Song of Songs is a paean to hetero sex and God’s union with man and the Church and each in terms of the other.

As the book Creation and Covenant recounts, this analysis of the Biblical narrative has been present with Christian teachers consistently throughout the history of Christianity.

The belief that sexual intercourse is special among human behaviors—that it can bring us closer than most anything else to our Creator—at least seems intuitively plausible to me. The notion that procreation, more than any other human activity, brings us closer to creating seems even more intuitively plausible. Even if I knew both of those things to be true, however, I would not feel compelled or even inclined to declare homosexuality to be wrong. I just don’t see why that follows.

In a sense, this is a leap away from currently-prevailing doctrines that might be viewed as quasi-Gnostic that assert that there’s no moral or spiritual valence to what we do with our bodies, and views fertility with something between indifference and hostility.

What a Christian might respond to Conor is that we view this importance of sexual union and procreation as signposts to what the Creator intended them to be used for.

I don’t think I’m overreading too much when I say that the implicit meta-story that Conor’s story here fits into goes something like this: “There’s this thing which is our sexuality, and given that it’s there we can do whatever we want, even if some aspects might be ‘holier’ than others.” But the Christian doesn’t view sexuality (or anything else) as something that just is there, but rather as something that has been put there for a specific purpose. Deviating from that purpose, then, is far from unimportant or morally neutral.

Or, to put it more starkly, if sex is a form of Christian worship (Eucharist, after all, means “thanksgiving”), then it matters a great deal how we do it, it makes sense that divine revelation would condemn ways of doing it that don’t accord with the “blueprint”, and it makes great sense that the Bible describes right worship in terms of marital union and wrong worship in terms of adultery.

Conor goes on to write that this is “counterintuitive”, but, of course, one might respond that heteronormativity hasn’t been counterintuitive for the vast majority of people throughout history (or throughout Christian history) and remains non-counterintuitive in most precincts outside America’s blue states and Western Europe. Not that it wouldn’t be true if it were counterintuitive, since after all the Gospel of Jesus Christ is full of counterintuitive things, like “love your enemies”.

Here’s what I expect to happen. As anti-gay bigotry declines, a greater proportion of Christians than ever before are succeeding in an obligation they’ve always had: to love gays and lesbians. While some who love gays and lesbians nevertheless think gay sex is sinful, I predict love of gays and lesbians will correlate inversely with the belief that homosexual acts and gay marriages are sinful. If I’m right, traditionalist Christians can at least take solace that when this cultural shift is complete, there will be more love and less hate here in America. It’s hard to imagine that Jesus wouldn’t prefer that to the previous arrangement.

I certainly join Conor in rejoicing that homophobia in America is at all-time lows.

And I will go even further and say that historically Christianity has been not only complicit but active in promoting anti-gay bigotry, and in many quarters still is, and that this is an everlasting shame, to be added in searing letters to the long list of our crimes.

Empirically, it certainly seems that Conor is right in saying that for far too many “conservative” Christians their support for “traditional” marriage was or is the result of anti-gay bigotry. In many ways, Christianity’s discombobulation in the West is the result of the dramatic failure to articulate and teach a coherent and profound Gospel vision. In the words of a young ex-Evangelical, via Rod Dreher:

In all the years I was a member, my evangelical church made exactly one argument about SSM. It’s the argument I like to call the Argument from Ickiness: Being gay is icky, and the people who are gay are the worst kind of sinner you can be. Period, done, amen, pass the casserole.

When you have membership with no theological or doctrinal depth that you have neglected to equip with the tools to wrestle with hard issues, the moment ickiness no longer rings true with young believers, their faith is destroyed. This is why other young ex-evangelicals I know point as their “turning point” on gay marriage to the moment they first really got to know someone who was gay. If your belief on SSM is based on a learned disgust at the thought of a gay person, the moment a gay person, any gay person, ceases to disgust you, you have nothing left. In short, the anti-SSM side, and really the Christian side of the culture war in general, is responsible for its own collapse. It failed to train up the young people on its own side preferring instead to harness their energy while providing them no doctrinal depth by keeping them in a bubble of emotion dependent on their never engaging with the outside world on anything but warlike terms.

Indeed. This portrait rings true to me (I wish I could say Catholics have done much better) and, frankly, a Christianity that is built on this deserves to have its ass handed to it in the court of public opinion.

And I will go further and say that if widespread anti-gay bigotry is the price to pay to preserve “traditional” marriage, then that is a price Christians should not be willing to pay.

I will also say that if and as Christians make the case against what some call “homosexualism”, they should be on guard against two heresies that I also see pop up, and that I’ll call “familialism” and “marriageism”.

Familialism is the heresy of idolatry of the family, and the belief that the institution of the family is an end of itself. My progressive friends are right to remind me that Christ said to hate your father and mother if they try to separate you from him. One knows many well-to-do Mass-attending Good Catholic families that freak out when their eldest joins the seminary, because he won’t give them grandchildren. The family that matters most to God is the Church, and human families are culturally-conditioned natural institutions. The family is important to God, but it’s not the most important thing.

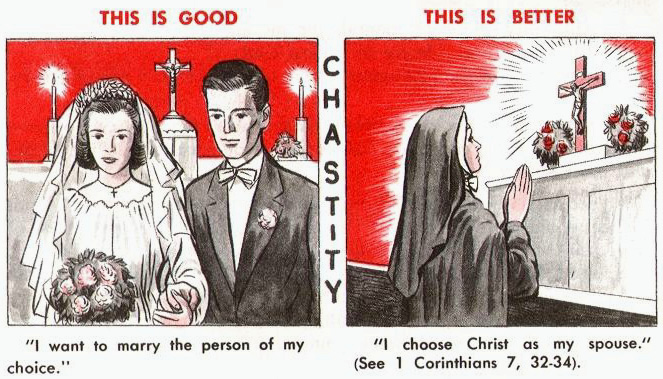

Marriageism is the heresy that says that marriage is the highest, or even the only, vocation for the Christian. The Bible is quite clear on this: both Jesus (Matt 19:12) and Paul (1 Cor 7:32-34) say that the highest vocation for the Christian is committed celibacy. This was continually held by the Christian Church until the Reformation, when Martin Luther put together an unprecedented view of marriage as the highest calling of the Christian and polemic against committed celibacy (this had nothing to do with his own interest in procuring marriage despite his monastic vow of chastity, of course). If marriage (as America’s Protestant-majority culture proclaims) is the only way to lead a flourishing life, then of course excluding same-sex couples is the height of cruelty. One searing paradox in all this is that if Christians are right that profoundly same-sex-attracted people are called by God to celibacy, then it means that they are called to a higher calling than married straight Christians like me. Which in turn means that the Church’s abject failure to articulate or put in practice what that means exactly is a catastrophic tragedy, for gay Christians, for the Church itself, and for the world.