Alex Jones believes that chemicals in the water are turning the frogs gay. If you don’t know about Jones, he’s a political commentator and conspiracy theorist known for his website, InfoWars. Known, perhaps, because the (chem)trail doesn’t end with homosexual amphibians: the Sandy Hook Shooting was a hoax, the government was behind the Oklahoma City Bombing, and 9/11 was, in fact, an inside job. He is best known, at this point however, for his affiliation with the Alt-Right and Donald Trump. Jones is a Christian, and this got me thinking: what is the relationship between American Christians and conspiracy theories anyway?

First thing’s first: Alex Jones, Donald Trump, and the Alt-Right are three different things, though, many have argued, closely-related in a variety of ways. What interests me here is how all three, in certain senses, invoke conspiracies to explain various problems. To take one example, all of them think the mainstream media is lying in some way. As they say: fake news!

The Donald tends merely to dismiss: outlets lie for his opponents, because, well, they are outlets for his opponents. Alex Jones, meanwhile, tends to advocate more shadowy explanations: Soros money, the New World Order—things of that nature (I just call Soros and the New World Order a symptom of, and another name for, capitalism respectively. But that’s just me). The Alt-Right, as a fairly-amorphous movement, would seem to fit somewhere in between (depending on the member, the theory, and a multitude of other factors).

Keeping in mind that here I will be treating three separate people as if they were one, I would like to pose a question: why do Christians turn to these theories to explain away—often very real—evils (I, for example, do think the mainstream media is biased and that its “fact-checking” is often merely interpretation; I also think corporations as well as other wealthy groups and people influence our societies and politics to the detriment of our communities)? Why not turn to other explanations (did somebody say Marx?)?

The answer, to me, seems to lie in how we understand evil. Conspiracy theories posit that real horrors (mass shootings, behind-the-scenes control of politics, etc.) have concrete causes. Often hidden causes, yes, but ultimately identifiable, often personal or institutional ones. Merriam-Webster, for example, defines the term thus:

[A] theory that explains an event or set of circumstances as the result of a secret plot by usually powerful conspirators.

Both “plot” and “conspirators” imply agency. Whether George Soros or organized super-national cabals, the deciding factor in these theories is an identifiable, human cause, something that can be located and pointed to—evil with a face.

This strikes me because of the Right’s general denial of structural issues, like, for example, structural racism, which implies (to speak generally) that most people are not subjectively racist—i.e. they don’t in a personal sense think their group is intrinsically superior to others—but that conditions in America make for objective racism. The word “objective” here might seem strange; at first glance, it might seem to mean that racism is some sort of indisputable and empirical scientific fact. But its usage here is philosophical. It finds its roots in Marx, and before him, in Hegel.

Without attempting to explain the philosophy of one of history’s notoriously most-confusing thinkers, I will merely say that “objectivity” here refers to what is socially true (in other words, it is not a question of empirical verification, but of how people relate to one another). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy might be helpful here:

Hegel […] had no problem in considering an objective outer world beyond any particular subjective mind. But this objective world itself had to be understood as conceptually informed: it was objectified spirit. Thus in contrast to Berkeleian subjective idealism it became common to talk of Hegel as incorporating the objective idealism of views, especially common among German historians, in which social life and thought were understood in terms of the conceptual or spiritual structures that informed them.

Okay, maybe that doesn’t help (see how hard explaining Hegel is? And to think I have to teach this stuff someday…). To clarify: human beings have their own wills, passions, desires, and so on, but these are informed by the context in which they live (the time period, their country of origin, their social class—yes, Hegel does talk about class—their gender, etc.). Their own particular subjectivity then informs these “objective” (because exterior and socially-formed) structures. To be very reductive, this is a form of notorious “Hegelian dialectics.”

Structural racism, then, is thought to have complex causes. It is not simply the idea that individuals are racists, but rather that our society and politics, under the weight of our history, still manifest certain forms of racism (certain police shootings are often seen as an example of this. It’s not that individual cops are bigots; it’s that non-black Americans, for a variety of historical and cultural reasons, have an unconscious fear of black people, especially in certain circumstances). Whether you agree or disagree, the point is that the form of structural racism is nebulous. Its causes are manifold and, to some extent, hidden; its remedy is equally complex and open to debate because its origins are shadowy. In other words and on this view, racism (of a structural sort) does not have a “face.”

The Right (by and large) does not accept that structural racism exists, and this is the case all the more with the Alt-Right., etc.). Because it cannot be traced to a philosophical idea [e.g. some thinker deciding society should be constructed such that non-white people would be structurally marginalized (in reality, of course, such thinkers did and do exist, but, as far as I can tell, many people on the Right would not say their influence remains in meaningful ways)], and because they don’t believe themselves to be racists, many on the Right deny that such a concept can have any meaning. What it requires is a physical face—a cabal, or something more mundane, like Richard Weaver’s pinning most modern ills on William of Ockham’s Nominalism).

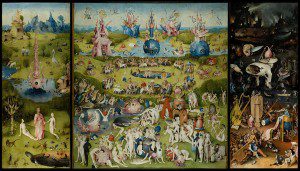

To view the world this way is to ensure that evil has a visage; it is to see evil as something (typically) chosen. Evil must be locatable not in a complex array of phenomena, but in specific individuals or institutions. Structural racism is merely an idea without referent while the mainstream news media is a group of people working (willfully) to undermine American (and often, on this view, Christian) values. For those who agree that such racism exists, however, evil is, in a sense, nebulous. It is a force that takes hold of people unwittingly (i.e. they believe they are choosing the good). No one “chooses evil”; rather, evil enters into us and slowly we give ourselves over to it. We receive it and cultivate it, but we do not, as such, choose it.