I’m always late to the party. I was watching a recent SNL featuring John Mulaney/Jack White, and they did a skit about Wild Wild Country. I hadn’t heard of the documentary, but I knew that for them to be satirizing it, there must be some buzz around it.

I looked into it and discovered the six-episode documentary series on Netflix. I turned it on at about 9 p.m. on a Tuesday night and watched the first five hours. It completely sucked me in.

What’s Wild Wild Country about?

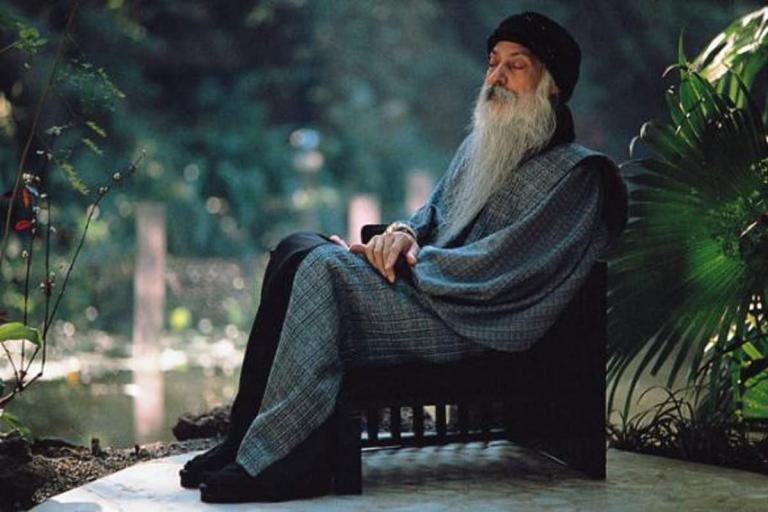

For those who are even later to the party than I am. Wild Wild Country tells the story of a cult surrounding an Indian guru, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (Osho). In 1971, a 40-year-old Rajneesh declared himself enlightened and started amassing followers. His movement was part enlightenment sect, part capitalistic endeavor, and part free-sex ashram. When India began squeezing the sannyasins (his disciples) out, they turned their eyes to the United States. After all, the U.S. Constitution protects religious liberty . . . right?

In 1981, they bought the Big Muddy Ranch near Antelope, OR, for $5.9 million. Because the ranch had enough people to support incorporation, it became the city of Rajneeshpuram.

The small Christian community of Antelope (population 40), was not entirely enthused about the new residents—and a standoff began. As time went on, the sannyasins took the battle to Antelope and eventually took over the town in a huge legislative upset. The city’s name changed to Rajneesh.

The reign of Ma Anand Sheela

The Bhagwan’s secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, operated as his sole spokeswoman and the public face of Rajneeshpuram. As the Oregon residents and news media outlets began demonizing the group, it forced Sheela into a very public position—and she quickly found that she thrived there. She loved being in the limelight and was often very provocative, saying things like:

“You tell your Governor, your attorney general and all the bigoted pigs outside that if one person on Rancho Rajneesh is harmed I will have 15 of their heads, and I mean it. You have given me no choice. Even though I am a nonviolent person I will do that.”

The commune started amassing weapons, and Sheela led a group of sannyasins on the largest bioterrorist attack in the United States. They also attempted to poison the Antelope water supply with blended beavers (you read that right), and planned to assassinate the United States Attorney for the District of Oregon.

At one point Sheela busses homeless people in under the pretense of community, but she intends to use them as a voting bloc. When they start getting unruly, she starts drugging their beer.

Ultimately, the whole thing collapsed. I encourage you to watch the series for all the gory details—it’s incredibly well done.

Wrestling with haunting questions

Most of the people I’ve talked to about the series have just said, “Yeah, weren’t they looney?” And I get it; it’s a pretty bizarre story. But it deeply affected me. As a Christian, I was left me struggling with some pretty challenging thoughts and questions. I thought I’d share a few of them.

1. Why can’t I identify with the Christians?

The frustration in Antelope was entirely understandable. Here’s a sleepy retirement community where everything’s hunky dory, and all of a sudden their life gets turned upside down.

But the immediate posture of this town is defensive and suspicious. As much as I want to give these people the benefit of the doubt, they don’t make it easy.

They’re fearful of the unknown, and like cornered animals, they became aggressive. They’re the ones that drag out the firearms first, carrying them around and firing them near the camp to frighten and intimidate. And when they quote the Bible, it’s a threat or an epithet. The sannyasins hadn’t done anything wrong yet and the town was already aligned against them. As things got out of control, there were so many opportunities to de-escalate the situation, but the citizens of Antelope and Oregon weren’t that interested.

When these Christians quote the Bible, it’s a weapon. Scripture only differentiates the good people (Christians) from the bad people. It doesn’t challenge the residents of Antelope to love more, to find common ground, or to forge a relationship with the sannyasins. No. It simply justifies their hatred of the cult.

It’s hard not to recognize the same attitudes that drive our current discussions about Muslims or immigrants. Fear is a primary ingredient for creating terrible people. It breaks my heart the public expression of Christianity is one of consistent opposition to everything and everyone.

2. Where’s our commitment?

Whether we’re talking about Jonestown, Rajneeshpuram, or the Branch Davidians at the Mount Carmel Center, we get so caught up in the sensationalism of their unhealthy behaviors, beliefs, and practices that we miss out on being challenged by their devotion to principle.

No matter what you think about the Bhagwan and his followers, it’s hard not to appreciate what they were able to accomplish. There was a single-minded dedication to their beliefs that I seldom see from Christians. The sannyasins were 100 percent committed to community, and the dedication it took to pull Rajneeshpuram together was impressive.

The groups we’re so keen to dismiss as cults always seem more committed to their beliefs than we are. I was raised to look down on Jehovah’s Witnesses and Mormon, but over the years, I’ve come to appreciate (and be challenged) their commitment to their beliefs. I’m always surprised by evangelicals who believe that God tortures unbelievers forever who can’t be bothered to evangelize. Meanwhile, Jehovah’s Witnesses are completely committed to sharing the gospel even though they don’t believe in hell.

I’m not saying that their commitment to their deals makes them right; I’m saying that it’s a pretty sad state of affairs if others are willing to do for a lie what you’re not willing to do for the truth. As I watched Wild Wild Country, I was confronted by our lack of dedication to our deepest convictions and principles.

3. When did Christianity stop being a movement?

At some point in the last couple thousand years, Christianity stopped being a grassroots movement and became the establishment. When that happened, it no longer focused on reconciling creation to God. Instead, we chose to rule by authority. We began aligning with nations and coercing “godly” behavior from citizens.

When settlers left England under the pretense of religious freedom, Puritans simply established a new order—a new version of the same garbage. Savages were killed or subjugated. Sinners were marched into the public square and put into the pillory. Today the church has aligned with conservatism under a charade of compatibility and preference.

But there’s something about being a minority that binds people together. It’s like all the social pressure from being misunderstood and unappreciated forges bonds and a commitment to ideals and principles. You see it in the early church, and occasionally it has sprung up in movements like the Anabaptists.

When I watch documentaries about cults, I’m drawn to the single-mindedness that opposition brings. It’s a shame that we don’t see that in Christianity. True Christians are a minority. The only thing Christianity has gained from power and influence is a sense of entitlement and complacency. We’re not as bent on serving and emulating Christ as we are on getting our way.

Any honest reading of the New Testament reveals a church that will always be a minority. That’s where its power lies. Once the church becomes a power-wielding majority, there’s no need to be connected to the vine. It draws its potency from another source.

Searching for more

I’m under no illusion that Rajneeshpuram represented a healthy religious movement, but something about Wild Wild Country convicted me. So many people are hungry for the connection found in communities like that—community that they’re not seeing in Christianity.

For the most part, our churches are places where people go a couple of times a week. It’s part of a spiritual to-do list. I have yet to be part of a church where people are that committed to each other. We’re too private. Too fragmented. Too disinterested.

And if we don’t care about our communities, why should anyone else?