An acquaintance lamented privately about a particular difficulty her family had faced, and the senselessness of it all. She had endured any number of trials past and present, but those had all had meaning. She could see in those other cases how the sacrifices and hardships were oriented towards a greater good. Now she faced a situation that was nothing but purposeless torment.

Adding to the insult, she was aware of ways to possibly relieve her family’s suffering, but every avenue that offered hope was also immoral, despite being generally accepted in the wider society. Some of the options that others enjoyed didn’t really seem that bad, compared to what she was experiencing. Was the Church just out to make her suffer needlessly?

**

Contemporary culture favors a utilitarian morality. What this means is that people tend to decide what’s right or wrong based on what seems to promote the greatest good for those involved.

It’s an approach that is sound if we are evaluating morally-neutral decisions. Trying to decide whether to buy lettuce or spinach? Consider the prices, what’s in season, which one your picky eater prefers, whether your aunt who’s allergic to spinach is coming to dinner, how much time you have to wash greens . . . lay it all out, balance the pros and the cons, and go with the one that makes the most sense.

Utilitarianism falls spectacularly short, though, in the moral realm. It’s the philosophy that inspired the Nazi government to kill off anyone who was unable to adequately contribute to society – the old, the weak, the disabled. It’s the philosophy that inspires parents to kill their children if prenatal testing shows the child won’t live long enough or well enough to be worth the trouble.

Because we are so steeped in our utilitarian culture, contemporary Catholics tend to slip into such lines of thinking when making moral arguments. When you argue that abortion is wrong because, “That baby might grow up to cure cancer,” that’s utilitarianism. Your argument is true, but it isn’t the reason we don’t kill innocent people. We refrain from killing innocent people because murder is wrong; each person has an inherent and inalienable dignity and worth merely by virtue of being human, no matter how much or little “use” his life ends up providing.

Thus it is with all questions of morality: The rightness or wrongness of an action doesn’t depend on its usefulness, it depends on the nature of the action. Legitimate self-defense is a moral action because of the inherent nature of self-defense, not because it is more or less useful than vengeance killings (always immoral) or pacifism (an option for most, forbidden for some). What this means is that sometimes doing the right thing turns out to be doing the less useful thing.

Because we live in a fallen world, doing the right thing may well be the thing that causes more suffering in this present life.

A consolation when we suffer for what is right is that we’ve kept our immortal souls out of eternal danger. More to the point: We have done what we were made for, and not violated the very nature of our humanity.

**

In the same way, when we talk about suffering, Catholics (and I do this sometimes) tend to slip into arguments about the usefulness of suffering. When you point out that fasting makes you spiritually stronger, or that unmedicated childbirth avoids certain risks of epidurals, or that Grandma and Grandpa would never have met if it weren’t for World War II, you are making a utilitarian argument in favor of suffering. These arguments aren’t false, but they aren’t the whole story either.

As much as we might point to the triumph of the human spirit in the many beautiful moments that follow unspeakable disaster, none of these triumphs justify the horror. People in Nepal weren’t crushed to death so that my daughter’s friend could choose to forgo birthday presents and invite her friends to come make blankets to send to aid the relief efforts. That’s nonsense.

It is good that a little girl responds virtuously to other people’s suffering, but we can in no way say that the purpose of the suffering was to spark virtue. We aren’t pawns being tossed around the cosmic chessboard as fodder for the valor of knights and rooks.

So what is the point of pointless suffering?

It doesn’t come with a point.

The scandal of it all is that there is no point. It is one thing to suffer for a worthy cause; it’s another to suffer for no good reason whatsoever.

And yet suffer we do. We suffer because other people do evil things, and we suffer because it’s a fallen world, where earthquakes smash houses and cancer ravages bodies. This suffering isn’t there to “teach us something” or to “cause a greater good.” It’s there because our world is infected with evil, and sometimes that evil reaches out and snatches the good from our lives. It is wanton destruction pure and simple.

If we had no god, or had a lousy god, we might not have much of a response to this purposelessness.

But we aren’t so bereft. Rather, God is both exasperatingly extravagant and fearlessly frugal.

God who made everything out of nothing doesn’t need a single one of us; He could dispense with all our services, lay us all out flat, and still get the work done. We think we desperately needed this seminarian who died too young or that scientist cut down in his prime, but God is able to see the Gospel preached or the breakthrough discovered even without the earthly presence of this or that person we found so very useful.

In the same way, God who made everything out of nothing can turn the most senseless destruction into the greatest of goods. He can turn loss to gain, death to life, emptiness into plenty.

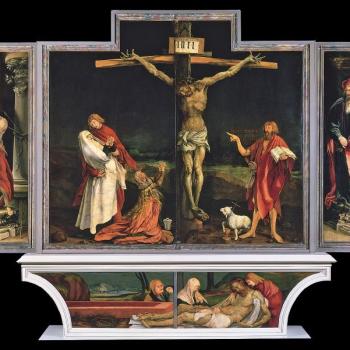

We who are made in the image of God have a similar gift, albeit on a much smaller scale. We can be deprived through senseless destruction of our greatest blessings, but live to see that deprivation used for good, if we allow it to be done. The suffering wasn’t so that good might come of it. The suffering was a senseless violence against us. But we can take that senseless violence and choose to put it to work, just as Christ put His crucifixion to work.

We can put it to work in the natural world, allowing good to come from evil. We can also take our suffering and offer it to God, and thus cooperate in turning torment and loss into a force of extraordinary supernatural power. One of the gifts we have as persons made in the image and likeness of God is the ability to choose take the meaningless and give it meaning.

Image by Gilles San Martin [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons