If I mention Cernunnos, what do you see in your mind? The cross-legged antlered figure from the Gundestrup Cauldron? Seán George from The Spirit of Albion? A mighty stag with no human characteristics? Perhaps you don’t see anything at all and instead feel the presence of a wise and powerful animal, or the essence of the forest.

If I mention Cernunnos, what do you see in your mind? The cross-legged antlered figure from the Gundestrup Cauldron? Seán George from The Spirit of Albion? A mighty stag with no human characteristics? Perhaps you don’t see anything at all and instead feel the presence of a wise and powerful animal, or the essence of the forest.

Some of our ancient ancestors carved their Gods in stone, and much of the work of the Egyptians, the Greeks, and the Romans has survived to our time. But the Celts were mostly different.

Last week I came across an excellent post titled Depicting the Gods on The Way of the Awenydd website. It’s a very good historical survey of the practices of the Celts in regards to images of the Gods. The writer quotes the Roman historian Tacitus, who said

“they do not think it in keeping with divine majesty to confine gods within walls or to portray them in the likeness of any human countenance. Their holy places are woods and groves, and they apply the names of deities to that hidden presence which is seen only by the eye of reverence.”

The blog writer (whose name I can’t find, beyond “Greg”) also said

Many of the surviving representations of Celtic deities were made by people who had become thoroughly Romanised, though they often also retain distinct Celtic features.

There’s an important point here, and it isn’t whether or not we should depict our Gods in material form. The key point is that however we depict the Gods, however we see Them or feel Them or recognize Their presence, Their reality is even greater.

I have been privileged to experience the presence of Cernunnos in ecstatic communion. Some of that experience is sacred and not to be shared. Some of it is ineffable – beyond the reach of words. But I can’t tell you anything about His true appearance from these experiences because it wasn’t part of them. Perhaps I’m not worthy to see it and perhaps I’m not capable of seeing it, but I suspect the main reason is that it’s not very important. What’s important is experiencing His presence, knowing (in that moment) His absolute reality, tasting His essence, and absorbing just a bit of His virtue.

The reality of the Gods is greater than any image we can make.

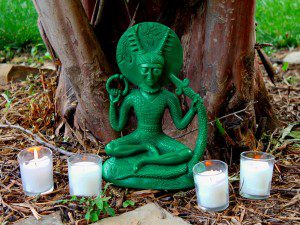

Now, this doesn’t mean Pagans should take after the Abrahamics and forbid “graven images” – a prohibition Muslims take very seriously, Protestants take mostly seriously, and Catholics and Orthodox pretty much ignore. Images of the Gods are useful. Whether three-dimensional, two-dimensional, or mental, they help us focus our attention on Them.

Now, this doesn’t mean Pagans should take after the Abrahamics and forbid “graven images” – a prohibition Muslims take very seriously, Protestants take mostly seriously, and Catholics and Orthodox pretty much ignore. Images of the Gods are useful. Whether three-dimensional, two-dimensional, or mental, they help us focus our attention on Them.

Sitting in meditation is hard. As the Buddhists remind us, our “monkey mind” is constantly jumping from the events of the day to what you have to do tomorrow to that sound you just heard outside your window. We are easily distracted. Having a physical image to hold our concentration, and to remind us of our intentions when our minds wander anyway, helps us to stay focused on the Deity of the Occasion, Their attributes, Their virtues, and most importantly, what They’re trying to tell us.

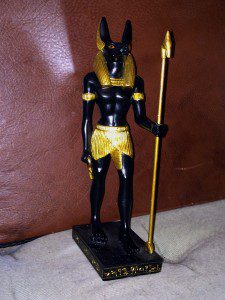

Beyond that, some traditions teach that images of Gods can become houses of the Gods: with the proper offerings and invocations – and with the cooperation of the deity in question – the Gods can take up permanent or semi-permanent resident in a statue. Thus the images are shown the reverence due the Gods Themselves. In our Egyptian temple rituals, we do our best to never turn our backs to the Gods, which was considered a sign of disrespect. This can be extremely difficult in a ritual where the intent is to present to the participants as much as it is to honor the Gods (the public was rarely if ever allowed inside Egyptian temples), but we do our best.

What should our images of the Gods look like? How should They be depicted? How should They be dressed? Many of us favor “authentic” images of artwork from antiquity – certainly I’ve found great power in the classical image of Cernunnos. But many of the ancient images of the Gods are simply dressed in the fashion of a powerful person of that time. Why should we not portray the Gods in the fashions of our time?

Back in April, Morgan Daimler explored this issue in a post titled Dressing Old Gods in a New World. It’s a short post that’s worth your time to read – here are two excerpts:

How do I see the Gods I honor? How do I picture Macha? Well I certainly can see her as a 1st century Irish warrior queen, but I can also see her as thoroughly modern, clad in dark jeans and a leather jacket, driving around in a dark red Ford Mustang.

and

Odin I can see easily enough in a variety of guises, from a nondescript older man in a grey hooded sweatshirt with the hood pulled down over one eye, to a younger man wearing an eye patch and a business suit – or jeans and a t-shirt for a Viking metal band. Because Odin is pretty flexible like that.

Our images – whether classical or modern; human, animal, or abstract – should reflect Them as best we understand Them. Good religious art – in any religion – doesn’t just draw pretty pictures. It tells stories, conveys emotions, expresses values and virtues, and connects us with all that through our senses. These elements are timeless.

But be careful with being tied too closely to familiar conceptions. A few years ago, there was a small uproar when Idris Elba – who is black – portrayed the Norse God Heimdall in the movie Thor. I didn’t join the uproar. 1) It’s a comic book movie, not a historical film, and 2) the stories of our ancestors (much less contemporary UPG) are pretty clear that the Gods can take whatever form they like.

At the end of the day, let’s remember the wisdom of our pre-Roman Celtic ancestors. While images of the Gods can be beautiful, powerful, and helpful, the Gods Themselves are far more than anything we can envision. Let us never forget we can also see them with the eye of reverence.