When – if ever – is violence ethically permissible? It is OK to punch a Nazi just for being a Nazi? Must protests always be peaceful and law-abiding, or are smashing things and starting fires sometimes good things? And what about curses and other magical operations – are they useful tools or traps waiting to backfire on the vengeful witch?

There’s been a lot of talk along these lines lately. Last week, Mat Auryn asked 28 witches and other magical practitioners for their thoughts on hexing, cursing, and binding. What he got was 35,000 words (the size of a small book) covering just about every imaginable viewpoint. It’s a long read but it’s well worth your time – and your serious consideration.

I was honored to be included with some of the most prominent voices in contemporary Paganism – you can read my answers on Mat’s site. Here, I want to explore the more general topic of violence and the ethics surrounding it.

What is violence? Violence is the use of force or the threat of force to achieve a goal, especially when that goal is coercing another person to do or not to do something. “Violence” is etymologically related to “violate” meaning “to break in, to disturb, to interfere.” The actual use of force is obviously a greater violence than the threat of force, but both violate the sovereignty of the person against which it is used.

Words can be violence if they carry the explicit or implicit threat of force. If you’ve ever been bullied you know exactly what I’m talking about.

If you don’t think magic can be violence, either you haven’t thought things all the way through, or your magic isn’t strong enough to be a threat.

Violence is expensive, messy, and always brings collateral damage. As I told Mat Auryn, I don’t believe in the threefold law. It’s not part of my heritage as a Druid, and I’ve seen no indication it actually works as described. I have seen evidence of what John Michael Greer calls “the strawberry jam effect” – you can’t work with it without getting it on yourself.

The use of force destroys things. It smashes windows, breaks bones, and pushes people into poverty. It disrupts the peace and destroys lives and families. It can never be completely controlled and contained. We are all better off if we avoid violence.

But violence is also effective – it’s one of the most direct ways to get what you want, particularly if you’re more powerful than the guy on the other side. Because it’s so effective, there’s always a temptation to use it, especially if you’re powerful enough to keep the collateral damage to others and avoid it yourself.

Non-violence is a peace treaty. Non-violence is a two-way street. It says we all recognize we’re better off if we can avoid the expense, messiness, and collateral damage of violence. It means we agree to renounce the use of force and rely on cooperation and non-coercive persuasion. It means that if we can’t agree on something, we mind our own business and stay out of each other’s affairs.

When someone breaks the treaty – particularly in a less-obvious way – our first response should be to call them back into our mutually beneficial relationship. The instinct for violence lies within all of us and when someone succumbs to it we are better off de-escalating the situation rather than immediately striking back. But all too often the one who instigates violence isn’t interested in restoring the peace but in flexing their power and remaking the relationship in their favor.

At this point the treaty is broken. If you feel you have an ethical requirement to maintain non-violence anyway, know that I respect your choice. But also know that history shows the odds of you avoiding serious harm are pretty long. There’s a reason why our instinctual response to threats is “fight or flight.” The third F (“freeze”) only works if it allows you to avoid detection.

When someone breaks the peace treaty and declares their intention to use force – in words or in actions – either we will respond or we will be subdued.

“Harm none” was a mid-20th century public relations slogan. People have been afraid of witches for as long as we’ve been human. So when Gerald Gardner began promoting his new religion of witchcraft in the 1950s, he had to do something to keep from being burned at the stake, figuratively if not literally. “See, we’re not maleficent magic users, we’re peaceful Nature-loving Goddess worshippers.”

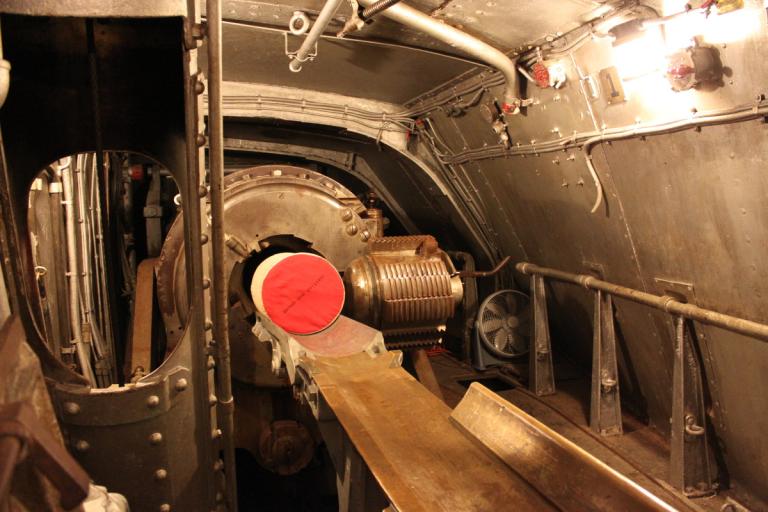

But witchcraft is ever and always about power, whether the witch is claiming her own inherent power, working with the power of Nature, or invoking the power of Gods and spirits. Magic isn’t easy, it isn’t clean, and it isn’t straightforward. It’s much simpler to just go take what you want, especially if what you want is rightfully yours. But if you are prevented from doing that by someone who is bigger, stronger, and more ruthless than you, what is your recourse?

“You didn’t beat me. You ignored the rules of engagement. In a fair fight, I’d kill you.”

“That’s not much incentive for me to fight fair, then, is it?” – Will Turner and Jack Sparrow, Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl

The rules are made by those in power, and inevitably they will be twisted and abused so as to keep themselves in power. If you want justice but the law is on the side of your oppressor, where do you turn? You turn to power that lies outside the law.

Violence is a terrible thing. An old proverb says that when the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem starts to look like a nail. Is that really a Nazi dedicated to destroying races he doesn’t like, or is he just an angry Trump voter? If you’re going to use violence you better make damn sure you’re right.

You also better make damn sure you can win. The pacifists who tell us violence is a never-ending cycle aren’t completely wrong. Striking back may feel good, but if it doesn’t bring real change all you’ve accomplished is upending the lives of others with the blowback.

But if you’re faced with no real choice?

Then in the words of the Morrigan “undertake a battle of overthrowing.”

So, can I punch a Nazi? I enjoyed watching “alt right” leader Richard Spencer get punched as much as the next justice-loving person. Here’s a guy born to incredible privilege who decided that wasn’t enough. He wants to remake America into a dictatorship of straight white men. And he’s slick enough to make it sound attractive to the disaffected and to those who prefer authoritarian rule. He’s a very dangerous person, and he needs to be opposed.

But if you’re looking for me to give you permission to punch him or other Nazis, you haven’t been paying attention.

Do their words rise to the level of violence, or are they merely advocating ideas you find offensive? Will your violence be a decisive response, or will it just escalate from punch to fist fight to gun fight to all out war? Who will be affected by the collateral damage and can you live with that? Perhaps most importantly, is there a more effective way to respond? I can’t make that decision for you, and you can’t abdicate your responsibility for making it to someone else.

This is a complicated situation and it requires careful consideration. Stop and think it all the way through. Every time you want to punch a Nazi. Every time you want to curse a fascist. Every time you want to bind a blowhard dictator wannabe. Every single time.

Sometimes violence is necessary. Sometimes it’s the only option. Many times it’s a big, big mistake.

This isn’t easy. It isn’t simple. Trying to make it easy and simple is how we get wars, atrocities, and witches tied up in their own curses.

Blessings to you as you make difficult but necessary decisions.