My father takes some thirty different medications, relating mainly to his bad heart. Both his mottled, discolored skin and his blood are so thin that when he wakes in the morning he is sure to find blood stains everywhere on his sheets. He is intermittently incontinent. His feet and calves are prone to swelling to hideous proportions. He loses his balance and falls to the floor four or five times a day. His diet consists almost exclusively of canned fruit and Frosted Mini Wheats. He sits in his lounger watching TV probably twenty hours a day.

His wife of nearly forty years died about two-and-a-half years ago (a passing I wrote a bit about here). He now lives alone in the house they shared for some twenty years.

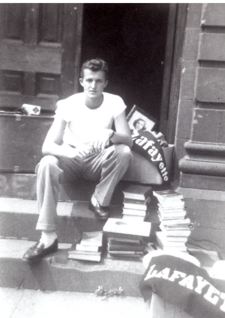

From the time I was eighteen years old until I was in my early forties I saw my father but two or three times. (The last time he came to San Diego, for a visit I wrote about here.) So in my mind he mostly remains as I knew him throughout my childhood and teen years. Then, he was a singularly imposing physical specimen. He is six-foot four, and as natural an athlete as any man ever was. You couldn’t beat the guy on a tennis court; his cannon-ball serve alone tore the racquet from the hands of most players — and if you did manage to return his serve, you’d find him and his long, long arms waiting for you at the net, impossible to pass. His racquet touch was ridiculously soft; he’d come barreling down on one of your shots like he was going to rifle it back through your rib cage, and while you were hustling backwards to save yourself and cover your baseline, he’d delicately drop the ball so close to your side of the net you’d stop dead in your tracks and right there swear to take up another sport.

He had played college basketball while still in high school. As a kid, I often watched him walk onto pick-up games on neighborhood courts, which he invariably turned into one-man exhibitions on how to sink freakin everything you shoot. He had this crazy stunt he’d pull, where, from half-court, he’s suddenly launch this ferocious one-man drive for the basket. Startled, the opposing players would start rapidly back-pedaling—arms waving like mad, crying out, “Whoa!” or “Jesus Christ!” He’d pound the ball on the pavement and take one monster leap forward — which would put him at the top of the key — and, his full momentum now gathered, would then turn the side of his huge upper body toward the basket, lean in, slam the ball down one more time, and take the final step that would launch him to the rim. He’d go down low for the leap, coil, rapidly rise up, and, just before his feet left the ground, freeze.

While everyone else was frantically airborne for the basket, he would turn and walk back toward the free-throw line. In the storm that he had created blitzing the basket, no one had noticed that on his second dramatic pounding of the ball on the ground — as all the rest of him was railroading toward the goal — he had left the ball on the ground, where it now sat patiently awaiting his unharassed return.

Two points.

Much moaning, and gnashing of teeth.

My father also loved to swim. For years he had been a lifeguard on Coney Island; when we moved to California, he was forever playing in the ocean like a seal. He moved through the water like that was the medium he belonged in, like his life on dry land was some elaborate ruse he maintained between times when he could get back to his natural life in the water. I always had to fight water; for him, it just moved out of the way.

Throughout my childhood and teen years my father was always starring in a play produced by one of the many theaters in the many San Francisco Bay Area. He had a leading man’s handsome face, a voice so deep and rich it made cats purr, moved like a dancer, had impeccable timing, and could memorize his and everybody’s part in about a week. He was a director’s dream, and they all used them whenever they could. By the time I was in high school he no longer even have to audition for parts; he would just get each theater’s upcoming season, see which parts he wanted, and pick up the phone. And bam: his year was planned.

I see this is threatening to become a book. Forgive me for the inordinately long post.

My point is simply that my father is dying; his once glorious body is now thoroughly ravaged. His mind is so sharp it’s frightening; he, my wife, and a guy I went to high school with are easily the three funniest people I’ve ever known. Being funny isn’t something my dad does. It’s what he is. He could no sooner not be funny than I could be Chinese.

And he’s as funny now as he’s ever been. The last time I talked to him on the phone, he busted into this whole routine, about how he’s incorporated falling down into his daily life, that was so funny I almost became incontinent. Time before that, he did this extended bit about his cat lying awake at night, plotting how to make his life even more miserable than it is. Then he did this other bit about how his phone and answering machine are so complicated that operating them necessitates him donning a pilot’s helmet and taking a seat before a huge switching panel installed in his bedroom closet.

That he’s so funny is why at fifty-five my dad was able to retire on the ranch he bought. People would buy stuff just to keep him around longer.

And I’m still writing this. This is ridiculous. Sorry again.

Right. When I was ten years old my dad — who, besides being one of the funniest persons I’ve ever met, is easily the angriest person I know I’ll ever meet — dropped to the ground from a heart attack. Basically, I’ve been waiting for him to die ever since. He’s had, like, six heart attacks.

Finally, now, his curtain really is coming down. A smoker all his life, his body is finally having its way with him.

He lives in North Carolina. He’d no sooner move to be near my wife and I than he would go skateboarding in a tutu. As he puts it, “Why in the hell would I move to San Diego? There’s nothing there for me.” And (trust me) he means exactly that.

He’s not exactly what you’d call emotionally sensitive.

He will insist upon dying as he insisted (despite his marriage) upon living: As alone as alone gets.

Anyway, this morning I heard something on the radio about Father’s Day coming up. So today all this sort of stuff has been on my mind. As it has been lately. As I suppose it always will be.

Follow-up post: “Happy/Sad to Say, I Won’t Miss My Father.“