The other day I found on my Facebook page a brief supportive note from a woman whose name, Elaine Liner, I failed to place. Later that day it popped into my head: she was the woman who, in 1991, had published one of my short stories.

I have no idea what the state is today of what used to called little literary magazines, but back when I was first trying to publish my short stories, “little literaries” were just about the only place in which any writer could publish work of that sort. Such magazines tended to fall into one of two categories. In the first were the more famous ones, which tended to come out of the writing programs of colleges and universities–Ploughshares, The Iowa Review, Agni, The Missouri Review, New England Review, and such publications. My chances of getting published in one of these prestigious journals (which were the ones read by book agents looking for new clients–but whatever) were roughly equal to Columbia University suddenly awarding me an honorary doctorate in English literature.

The other kind of little little literary magazines were those published by everyday people whose love of short stories compelled them to put out a call for short stories, don an editor’s cap, reach into their purses, and make of themselves a publisher. Privately funded and lovingly produced, these publications ran the gamut from five photocopied pages folded and stapled together to polished, well-received periodicals that could hold their own against any literary journal in the country.

I spent a full twelve years sending out and having my short stories rejected by both kinds of little literaries. I collected so many rejection letters it’s a wonder I ever managed to climb out of bed at all.

Finally, out of a despair so deep just thinking about it now makes me want to run out and jump down a well, I gave up trying to write short stories that I thought were how short stories were supposed to be written, and instead, in the throes of what amounted to a kind of creative trance, started writing these insane little stories, of the sort I’ve shared here on my blog via The Smiling Bird, Oscy Gets a Life, and The Story of My Life.

In one week nine of my new stories were accepted for publication, each by one of the better privately-funded little literaries.

Every day, for six days in a row, I found in my mailbox another notification that a story of mine had been accepted for publication–and on three of those days, I found two such notices. That was a week I’ll never forget.

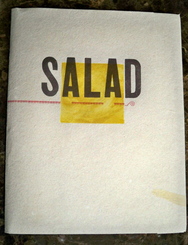

One of the publications from which I received such a notice was SALAD, from LaLaLa Press, out of Dallas. The editor of SALAD was Elaine Liner. The publication was 5.5 x 7.75 inches, and gorgeously done. Its cover was of thick, handmade paper, folded and glued just so; its pages, I saw, were designed by Caryl Herfort, clearly a top-rate artist. (I’m sad to say that just now my Google search for Caryl, with whom I’ve never had any contact; turned up this Facebook memorial to her). This was no regular little literary magazine. Clearly, this was an act of love.

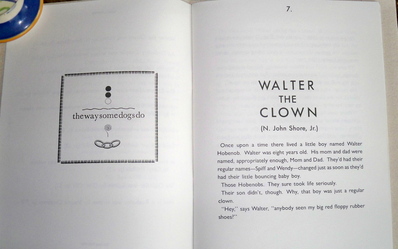

To give you a sense of the thing, let me show you a bit more of it–or at least that part of it that certainly thrilled me:

I should have taken more/better pictures of the SALAD’s internal pages–but you get the idea. Each story or poem in the publication had accompanying it a piece of design or artwork like you see here on the opposing page of my story: some little stand-alone graphic that just … nails it.

You know, this is the dream, really. This is how you long to see your stuff presented. And when you’re just starting out–and you know you’re doing work that’s not like anything out there?

Man, then something like this–someone who cares enough to treat you stuff like this–makes all the difference in the world.

Thank you, Elaine Liner. It was good to hear from you again.

(Elaine is now theater critic for The Dallas Observer [scroll down the page to see her review of “Flaming Guns of the Purple Sage”]; she is also co-founder of Theater Jones–which, unsurprisingly, is a public service to Dallas’ arts scene.)

Here is the story of mine that Elaine published, lo these many years now gone by:

Walter the Clown

Once upon a time there lived a little boy named Walter Hobnob. Walter was eight years old. His mom and dad were named, appropriately enough, Mom and Dad. They’d had their regular names—Spiff and Windy—changed just as soon as they’d had their little bouncing baby boy.

Those Hobnobs. They sure took life seriously.

Their son didn’t, though. Why, that boy was just a regular clown.

“Hey,” says Walter, “anybody seen my big red floppy rubber shoes?”

“Now, come on, Walt,” said his dad, Dad. “I want you to take off that silly fright wig and that ridiculous red nose right this very instant. I’m serious. I want you to start acting normal, young man—and I mean right now.”

“I’ll sure try, Dad,” said Walter sincerely. Almost immediately, though, he turned into a clown again. “But first, how about a nice big sniff of this flower I have buttoned to my lapel?”

No matter what his parents did, or how they threatened and cajoled, for the life of them they couldn’t get their little Walter to stop behaving—and dressing—like a circus clown.

“Where does he get it?” moaned his dad.

“Maybe one of us has clowns in our family tree,” suggested Mom. “You know: maybe Walter inherited the clown gene.”

“Hmmm,” said Dad. “Any clowns in your family that you know of?” Mom thought about it for a minute, and then said, “No. Yours?”

“No,” said Dad resolutely. “Never.”

So, that wasn’t it.

Walter’s acting like a clown all the time wore pretty thin pretty quickly on the powers-that-be at Walter’s public school, the Play Along Elementary Drill House.

The principal of the school called up his parents.

“He hit another boy in the face today with a cream pie!”

His teacher called, too.

“He pulled on his big polka-dot tie today, and his pants flew up and down his suspenders like a window blind! And that underwear!”

“Sorry,” said Dad.

“Sorry,” said Mom.

They went to Walter.

“Son,” they said, “what’s the matter with you? Don’t you know how you hurt and disappoint us when you insist on wearing that orange wig and those huge red shoes? I mean, look at us. We’re normal people. Normal people have normal children. But what happened to you?”

Walter made the saddest face imaginable, with his red painted frown, and slowly blinked his big, heavily mascaraed eyes a few times.

“Sorry,” he said, looking up at them.

And he was sorry, too, when about a year later his parents finally kicked him out of the house. He had just come home from school, and when his mom and dad saw that he was wearing a brand new bright blue fright wig, apparently the same thing in both of them snapped.

“All right!” they said, throwing him out the door. “That’s it!” Hurling behind him his favorite red and white checkered pants and his big red shoes and his spare round nose, they said, “We just can’t take being Bozo’s parents another day! Bye! Write us when you get normal!”

“But, Mom!” cried Walter. “Dad! You can’t kick me out this way! How will I survive?”

“You’ll do fine,” they said. “Everybody loves a clown. But remember, Walter: Nobody wants to live with one!”

They slammed the door; and that was that.

Walter was so crestfallen that he plopped down onto the lawn, right there in front of his ex-house. Pretty soon a little dog came by, a mutt. When it saw Walter, it ran right over to him and started jumping around and trying to lick his face, the way some dogs do.

“Hey, big fella,” said Walter. “Sit.”

The dog sat.

“Speak,” said Walter.

The dog arfed.

“Roll over,” said Walter. The dog flipped onto his back and happily pawed the air.

“Close enough,” said Walter. “You’re a good dog. Mind if I call you Spot, since you have that big spot on you? Want me to do some tricks for you, Spot? Watch this.” He pulled three colored balls out of his coat pocket and started juggling them. “Pretty cool, ‘eh?” he said. “Can you believe I got kicked out of my house?”

Right down the block from Walter’s house was a school bus stop. As Walter was juggling, a bunch of kids were just piling off the bus after a hard day spent adding numbers and spelling and trying to figure out maps and so on.

“Hey, look!” yelled one of the kids. “It’s Walter! He’s juggling! And who’s that ugly little kid with him? C’mon, you guys!” They all came over to see Walter and the kid who turned out to be a dog.

All the kids loved Walter. They always had. Walter was their kind of guy.

“Hey, Walt!” they said. “What’re all yer clothes doin’ outside?”

Walter stood up and pantomimed the whole story of how his parents had thrown him out of the house.

Once the kids understood what happened, they were outraged.

“That’s ridiculous!” said one particularly hearty kid, chubby Andy Watkins.

“Sure is!” everyone agreed. Then somebody said, “C’mon! Let’s go build our pal Walter his own circus, so that he can have a place where he’ll always belong!”

All the kids roared their approval—and in about a week, way on the outskirts of town in the middle of a big empty field, those industrious little dreamers had finished building “Walter’s Circus,” complete with a big-top, and sawdust rings, and wooden bleachers and everything.

Almost immediately, people started pouring in from miles around to see the new circus.

And all of the kids in the neighborhood moved out of their houses and came to work in the circus with Walter.

There was Mikey, The Boy Who Does About a Million Summersaults And Then Walks Like He’s Drunk!

There was Sharon, The Girl Who Can Spit A Watermelon Seed Practically 15 Feet!

There was Ruthie and Angela Ronzo, Twins Who Can Dress So Alike You Can Barely Tell Them Apart!

There was Andy, The Kid Who Can Eat Almost A Whole Pie If It’s Cherry!

Admission to the circus, all acts included, was fifty cents—except for all the parents in Walter’s town. They had to pay a thousand dollars a piece to get in. And even then, they were only allowed to see the permanent, boring displays, like the papier-mache animals and the lame wax sculptures. And they had to look at those through a small, low, narrow window, which the kids encouraged Spot to keep nice and smudgy.

***************************************************************************************************************