Apropos to my last post, Six Things to Know About Sexual Abuse and Forgiveness, I late last night wrote as a status on my Facebook page:

Apropos to my last post, Six Things to Know About Sexual Abuse and Forgiveness, I late last night wrote as a status on my Facebook page:

I think if there’s one message that victims of abuse need to hear and believe, it’s that every single ounce of the total power of their lives is still with them.

By way of a response I later got emailed this (which of course I use with permission):

I just wanted to respond to your last Facebook status, about victims of abuse needing to know the total power of their lives is still with them. When I read it I immediately started to cry and I just couldn’t stop. I can’t find the words to explain how much that means to me. In one sentence, you’ve shattered a wall I’ve spent years building and reached a part of me that I’ve always kept hidden at all costs because I was afraid. For the first time in my life, I feel like I’m not alone. Thank you.

In reference to our brief e-chat last night, this morning this same person wrote me this:

This is the first time I’ve told anyone anything, ever. I’m still too scared to share. I would be lying if I said last night was easy; I didn’t get much sleep. It probably sounds stupid but I felt exposed, like I had been cracked open. I know this is a good thing, but it’s so, so hard.

In response to which I wrote her all that follows, which I thought I might also share here:

No, this feeling you have of what amounts to irrational, panic-inducing vulnerability doesn’t sound stupid at all. It sounds like exactly the way victims of childhood sexual abuse find themselves feeling all the time—especially if anything comes up having anything whatsoever to do with that abuse—or with sex, or parents, or their bodies, or … the wind blows in a way that feels a little off to them—which it does, all the time, because they’re exquisitely sensitive. In the realest possible way, victims of childhood sexual abuse are, through their trauma, transformed into beings who are, in some really essential ways, more human than people who weren’t sexually abused as children. Because virtually everyone trips, hard, about sex. Everyone is insane about their parents. Everyone is a freak about their own body. Everyone is so emotionally sensitive that if it comes to their attention that on their grocery list they so much as misspelled the word coffee, you practically have to restrain them so they don’t commit hari-kari.

Everyone is too sensitive for … well, life. Everyone feels inadequate to the ever-overwhelming task of life. They feel that way because they are inadequate to the ever-overwhelming task of life. We all are. None of us knows what the frack is going on out here, or what if anything we’re supposed to do about it.

But people who as children or young people were sexually abused? They have an extra burden in life, and it’s not a good one. Namely, they were robbed of their safety zone. When the bad thing happened to them, the first thing they learned was that their natural instincts for protecting themselves not only are not worth a damn, they actually work against their well-being. That’s an exceptionally … unhelpful message to receive. The one thing people use to keep themselves sane and protected is their innate sense of what will and will not harm them. The world (thank God) comes in patterns, and we all learn to read those patterns, and to thereby see when something threatening is headed our way. We hear a train whistle; we feel the ground rumbling; we look down and see we’re standing on train tracks; we step the heck off those train tracks. Done. We’re safe.

But the person who as a child suffered sexual abuse at the hands of someone whom with all of their heart they loved—someone in whom they deeply trusted, someone whom they instinctively understood would always protect, care for, and love them? When that person comes at them and destroys their universe?

When that happens, the one thing that the poor victimized child right away learns is that life—virtually, literally, and forever—cannot be trusted. What they have immediately imprinted on every fibre of their being is the certain knowledge that anything, at any time, from any quarter whatsoever, can come flying out of nowhere and obliterate them. Furthermore, there isn’t one damn thing they will ever be able to do to prevent that from happening. How can they, when so obviously their Early Warning System is so severely broken? Their EWS doesn’t work. It’s useless. It didn’t warn them.

They did get hit by the train.

They cannot trust life; even worse, they cannot trust themselves to know when, where, or how life is going to randomly start slaughtering them.

Not exactly a swell thing to have weighing down your backpack as you begin your travels through the great big adventure we call life.

But. That’s what happened to abused children when they were kids. As adults, they necessarily come into possession of powers that as children they certainly did not have. And chief amongst those powers is the ability to put on a hard-hat, go back and look at the control panel for their Early Warning System, and see that—hey, whaddaya know!—the thing is perfectly fine. It’s not broken at all. It just never got the chance to work. Some [bleep] supervisor of theirs switched it off before it was ever fully up and running.

And then, boom: a switch here, and plug here, a few lights turned on, and their EWS is every bit as operational as anyone else’s.

Then that person sees: they didn’t fail themselves. Life didn’t fail them, either. The only thing that failed them was one sad, angry, miserable, lonely, deeply tweaked human being.

They see that what happened to them was never really about them at all. It was always all about their abuser. They were powerless to stop what happened to them, and they were powerless to stop it from affecting them the way it did. That’s it. That’s all that happened.

In the final analysis, the victim of childhood sexual abuse was never anything but the one thing that no one on earth can ever stop themselves from being: good ol’ fashioned unlucky.

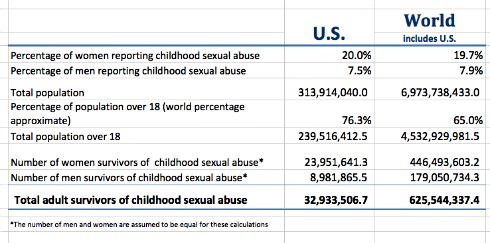

Finally, if I might say one thing about survivors of childhood sexual abuse feeling alone—which, invariably, they do, since what happened to them is so deeply intimate and personal that the last thing they’re inclined to do is share it with anybody. Below is a table I made based on data from two sources: a 2009 study published in Clinical Psychology Review that examined 65 studies from 22 countries, and a 1994 study published by Princeton University, Current Information on the Scope and Nature of Child Abuse.

So the good news (such as it is) is that no one member of any group that includes 625,544,337 people is ever anywhere near alone.