Earlier this week, Tony Jones noted that many Christians who are calling for a faith more engaged with the world have surprising little to say about God. A good point–and one that’s particularly disturbing over the long haul. Think, for example, about how many institutions that were inspired by faith have completely cut off any official connection to God-talk. Hospitals, for example. I’m just back from visiting one this afternoon. The orderly who was taking my friend to surgery looked at me with impatience when I paused to pray for thirty-seconds. Absent its history in the works of mercy, the contemporary hospital is almost entirely given over to market forces. If the hospital is just another corporation, who has time for prayer?

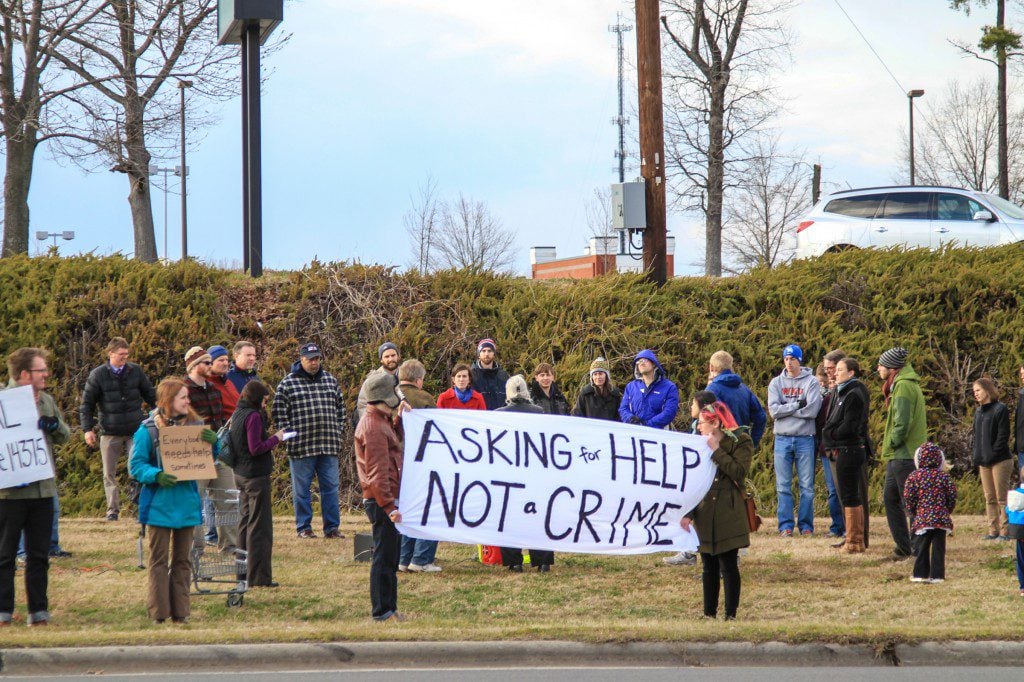

But a faith that engages the world—that is, a faith that practices the works of mercy and follows up with a pursuit of justice—will inevitably bring us face-to-face with suffering. This is, inevitably, where we have to figure out what we really believe about God. A peculiarly Christian hope rests neither in avoiding suffering nor in accepting it, but in enduring it for the sake of a reward that we must pass through this present darkness to receive. And this makes all the difference for how we seek justice and love mercy in a broken world.

The servant whom the prophet Isaiah anticipates as the hope of God’s people is “a man of sorrows, and familiar with suffering’ (Isaiah 53:3). He does not overcome evil by mounting a crusade against it. This servant does not beat our stubborn selfishness out of us. He understands the nature of our problem—that “each of us has turned to his own way’ (53:6). What hope, then, does he offer? “The Lord has laid on him,” Isaiah says, “the iniquity of us all” (53:6).

This is the root of what Christian teaching calls substitutionary atonement. Out of context, it is often derided as a cultic notion that betrays a cruel God. What kind of God, critics ask, would demand a substitute victim on which to exercise his wrath so that the rest of humanity does not have to suffer? What’s more, what sort of twisted Father would ask this of his Son? Most people are not relieved to learn that Jesus had to suffer and die a cruel death so God would not damn them to hell.

But this is not the good news that Isaiah anticipated or that the New Testament proclaims. In the context of original sin, which Christian doctrine helps us to name, Isaiah’s suffering servant is one who sees clearly the root of human violence. Though we are inextricably connected to others in the membership of creation, our relationships are fragmented by sin. The twisted desires which Adam and Eve pass on to their sons lead to murder in the second generation of humanity. And this conflict of personalities is quickly magnified to conflicts between societies after the confusion of languages at the Tower of Babel.

In short, we are all caught up in a cycle of violence. Each selfish act inevitably affects our fellow human beings and, in something of a domino effect, leads them to react in some selfish (and self-defensive) way. Isaiah sees with prophetic clarity that the only hope of ending this cycle would be for someone to take sin upon them self without passing it on to others. But who could muster the inner resources to suffer without retaliation—to endure the world’s violence in love?

The answer the New Testament proposes is God. Given the selfishness in our DNA, there was no hope that any of us—not even Mother Teresa or Gandhi or the Dali Lama—was ever going to be able to interrupt the cycle of violence by only returning good for evil. Thus the substitution that animates the hope of Christianity is the incarnation—the belief that God took on human flesh in Jesus Christ to do for us what we could not collectively or individually do for ourselves. “Being in very nature God,” Paul explains, Jesus “did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant” (Philippians 2:6–7). This is a servant that attentive readers of Isaiah recognize.

God acts definitely in Jesus to become our suffering servant, to overcome evil with good. He lives the life of the true human being, attentive to every word of God and faithful to every relationship with other people and the world around him. To people who have been crushed by this world’s broken systems, Jesus’ life is a welcome interruption—an eruption, even, of good news. But to the powers who are invested in the way the broken system works, Jesus is an enemy who must be killed.

Jesus’ willingness to suffer a criminal’s death on the cross, having done absolutely nothing wrong, is the ultimate sign of God’s love for us. This is the substitution that both atones for our sins and makes it possible for us to live at one, even with our enemies. Thus, substitutionary atonement is not an embarrassing dogma, but genuine good news.

And it is good news that we’re going to need if we are to face the unavoidable suffering that the pursuit of God’s justice brings.