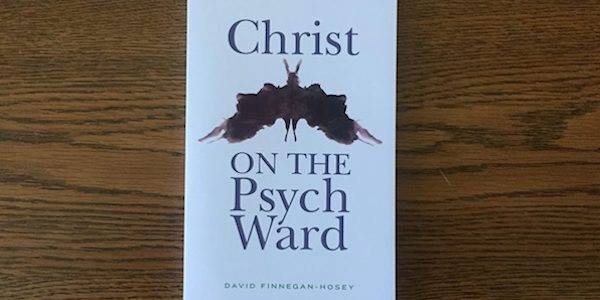

I have the pleasure of sharing a great conversation I had with my good friend David Finnegan-Hosey about mental health, faith, and his new book Christ on the Psych Ward. Definitely check out his book! He’s got a powerful story.

MG: Maybe start off by telling me what happened in your life that allowed you to meet Jesus on the psych ward.

DH: Sure. Well, in the summer of 2011, I had just finished my first year of seminary. It had been a good year and from the outside, it really would have seemed like there was nothing wrong in my life. And internally, I was completely falling apart, and I didn’t really understand why. It was scary.

It started as a long spiral downwards and then there was one week in particular that was just terrifying. My mind was all over the place, my emotions were all over the place. I was hurting myself, which somehow felt like it was a way to express the internal sense I had of having all these jagged edges. I felt like I had run out of words and didn’t know how to communicate what was going on with me, but then I was really ashamed of it as well.

So by the end of the week, I realized I was really contemplating suicide, and I somehow was able to reach out for help — first to a suicide prevention hotline, then to a friend, and then finally my friend put me in touch with an acquaintance of ours, a chaplain at a local university, who drove me to the hospital and helped me check myself in.

And that started about a six month journey in and out of various hospitals until, while in a longer term program at Silver Hill Hospital, I was diagnosed with type II bipolar disorder and started on a path to some form of healing and recovery.

MG: Did your spiritual upbringing leave you with any particular perspective on mental illness? I know sometimes that’s an issue for folks.

DH: So for me, I didn’t have a lot of stigmatizing messages about mental illness in my spiritual upbringing. Nobody ever tried to exorcise the demon of depression out of anyone in my church — that would have been way too impolite. We just never, ever talked about it. Looking back it’s the silence, rather than the overt stigma, that is so notable.

What I did have was a family history of mental illness, and parents who had done some of their own work in being willing to talk to me about that. So I think I had some groundwork laid in terms of awareness that a lot of folks just don’t have.

And I think that’s important for folks to know in reading the book — there’s a couple of chapters where I actually say explicitly, “Look, if you grew up hearing that mental illness is a demon, you maybe can just skip this part.” My story isn’t everyone’s story, and that’s important to acknowledge.

MG: So was there an actual Jesus on your psych ward? Sometimes there are.

DH: Well, that’s an interesting question, right? Because it raises the question of “What’s an actual Jesus?” or, more to the point, “What actually is the body of Christ?”

So there wasn’t someone who thought they were Jesus with me in the hospital. But I would say that I really did encounter the body of Christ on the psych ward in a way just as powerful, maybe much more so, than I ever have in a church building.

MG: Say more about that.

DH: Well, we were all together in a place designed — ideally, at least — for healing, and we could all be honest about what was going on with us, about the stories and the journeys that had brought us to this place. And we could be mutually supportive of each other, comfort each other, tell each other the truth.

I saw God in that.

In the book, I talk about the passage in John’s gospel, where Jesus calls the disciples “friends” and then promises to send them the Spirit as an Advocate/Companion/Comforter.

And I saw that modeled on the psych ward, and in groups at Silver Hill, in a way that I think I often don’t see in a lot of churches, where we put our church clothes and our church faces on and sort of pretend to be ok.

So a lot of the talks I give in churches or to chaplains are about how we can be better at being in ministry with folks who have mental health struggles. And that’s a really important topic. But really the experience that led me to write the book wasn’t about things churches could do for me so much as about things churches can learn from a place, like the psych ward, that’s often surrounded by a lot of stigma and silence and fear.

All of which is to say: I encountered grace in the course of my hospitalizations. Not because I or other people with mental health struggles are somehow better or more interesting or more special or something, but because there was an honesty, an up-against-ness with the reality of hurt and brokenness in our lives. And I think places where that’s true, that’s where Jesus looks and says, “There. I want to go there.”

MG: I like that phrase up-against-ness. It seems like the rawest authenticity tends to emerge in that kind of environment.

DH: I’m glad you like it, I couldn’t come up with a real word there haha. Any other questions for me?

MG: How has your definition of church changed as a result of your experience of mental illness?

DH: That’s a great question, I really had to think about that for a second. I’m not sure my definition of church has changed so much as my orientation around church has changed. I think The Church, and individual churches/congregations, need a real openness to the way the Spirit moves outside of the bounds of what we tend to think of as church. It’s not that I necessarily define church differently, it’s just that I think this thing we’re defining as church needs to really be paying attention and discerning the Spirit outside of its boundaries.

There’s this passage in Jurgen Moltmann’s book, The Church in the Power of the Spirit, that I think provides some helpful theological language for this idea. I’m paraphrasing, obviously, but he basically says something like: The more the church understands that it is created by, and exists within, the movement of the Spirit, rather than being something that contains the Spirit, the more it can understand itself as one vital expression of God’s mission for the world and not as the one and only thing going on. And then the more it can see the movement of the Spirit elsewhere without jealousy or derision. [end paraphrase]

So I think that’s what I experienced in these various hospitals — this movement of God’s Spirit outside of the walls or the definition of “church,” and one that has something really important to say about how we do church, about the vulnerability with which we engage in church, about the seeming “weakness” of the grace that calls the church into being in a country and a world that tends to be very impressed with strength and power.

The church that sees itself as part of that world of strength and power is going to (a) be really concerned about protecting its own strength, whether thats a concern about numbers or avoiding controversy or whatever, and (b) is going to see ministry with, say, folks with mental health struggles as helping them or “ministering to” them rather than as receiving the gift and the graces that folks with mental health struggles bring to the church

And you could take “mental health struggles” in that last bit and replace it with all sorts of things, all sorts of human experiences, and the point would remain.

MG: I like your point about the “weakness” of the Spirit’s work in contrast with the strength that we expect to see because of our worldly values.

DH: Yeah, that’s important for me.

MG: Does this experience of the Spirit’s “weakness” shape how you understand God’s control over the universe? John Caputo argues for a “weak” God who isn’t completely in control. How does that jibe with your theology of God’s sovereignty?

DH: Right, so I’d say a couple of things. First, my book takes my experience, and my experience during a pretty limited time period of my life, as its starting point. So the book comes with this presupposition that our own experiences are a legitimate source of theological reflection. That’s very Methodist, of course; it’s also very Ignatian, and I’m sitting here at Georgetown University, a Catholic University that’s in the Jesuit/Ignatian tradition.

Anyway, all of that is to say, when I talk about God’s weakness, I’m not necessarily making a systematic claim, at least not at first. I’m talking about the way I was actually able to experience or encounter God in the midst of a time of crisis and struggle. So that’s the first thing.

The second thing I’ll say is this. When I was in college, I was an international studies major, so I talked about sovereignty a whole lot before I ever talked about it in a theological sense. So I think I have a bit of a different relationship with the term than some other folks, especially maybe folks who grew up in a Reformed tradition (I’m new to the UCC, so this is so interesting to me).

So sovereignty, in an international relations view, is about a country being able to exercise agency and control within its own borders — to not be controlled by some outside force. But of course, in a globalized world, this definition is under constant challenge, and there’s increasingly a realization that the stickiest problems we have in the world today — climate change, refugee crises, genocide — present challenges to that traditional view of sovereignty.

So when I think of God’s sovereignty, I think about that. It’s not that God is 100% in control of every single thing that happens — it’s that God, in God’s self, exercises agency and freedom, but God is much better than us at realizing that doing that well means opening up, means challenging the traditional boundaries and borders of that agency.

God’s power is expressed in the world in a way that a world obsessed with defending borders often misses because it interprets it as weakness rather than power. But it’s still God’s power.

So I think Caputo would probably have a more systematic or total understanding of the weakness of God, whereas I’m coming at it more from an experiential or existential standpoint, and it’s through that experience or that standpoint that I approach the more systematic questions.

(Caputo’s book is going to spend a whole lot more time arguing about creatio ex nihilo than I am, just as one example, though you don’t necessarily have to include that in this interview haha)

MG: So let’s go a different place in talking about God’s nature. The God depicted in the Old Testament seems to have some pretty major mood fluctuations. If the God in the Bible went to a therapist, would he be diagnosed with bipolar? To put it differently, is it right to presume that God is perfectly rational, serene, etc or is that imposing a problematic norm on God?

DH: Well, I’m not a diagnosing mental health professional, so I wouldn’t offer a diagnosis of any person, much less of God haha. But as someone who has a mood disorder, I really do appreciate that the biblical depiction of God isn’t this distant, unemotional monolith of a Being. God gets mad, and God cries, and God sometimes throws tantrums. And the people of God, in encountering and responding to this God, they express the full range of human emotions — the book of Psalms being a pinnacle of this expression within our tradition.

The Psalmists rejoice and complain and breakdown and beg and curse and rage and then rejoice again. I can relate to that.

MG: So based on that, would you say that the Bible problematizes Western enlightenment notions of sanity?

DH: Hmm. Say some more about that.

MG: I just wonder to what degree we ought to be calling into question the default Western understanding of “sanity” as a sort of stoic “well-adjustedness” that can often signify an aloofness to one’s own emotions and wounds.

DH: Yeah, that’s interesting.

In Dialectical Behavior Therapy, which is the type of therapy that the longer term program I did at Silver Hill was based in, they talk about the idea of “Wise Mind.” Which is when you can find a sort of balance between your emotions and your rational mind.

“Equanimity” might be another way of saying that — not that the storm surges aren’t there, just that I’m able to ride them out.

Because to be clear, when I’m in the middle of a bipolar episode and my emotions are all over the place in this really extreme way, it sucks, you know? It’s not something I want or that I like.

But the opposite of that, a sort of completely detached, non-emotionality — that’s not the goal either. That’s like if I were to jack my medication levels up way too much — just sort of be zombified. So I think I’m searching for a sort of balance.

But I don’t think God has to wait for me to find that balance to be present and active in a gracious way in my life, or in anyone else’s life.

And of course, there are systems questions to address here, too. “Well-adjusted” will always be a problematic metric, because I want to be well-adjusted to life, but what about when that means being well-adjusted to injustice? What about people who are feeling a persistent anger or a persistent depression because they’re constantly the target of oppression or violence? The problem there isn’t internal to their psyche, it’s systemic. To be well-adjusted to an unjust system is to maladapt one’s own soul. As Dr. Cedric C. Johnson, my pastoral counseling professor in seminary, would always say: “An adaptive move in one context can become a maladaptive in another context.”

MG: Exactly. I think what I always want to resist is the tendency, especially among white men, to use “equanimity” as a means of giving yourself the higher moral ground in an argument and delegitimizing someone else’s perspective because they’re “crazy” or “emotional.”

DH: Right, yeah, that’s important. Emotional intensity isn’t the same as mental illness, for one thing. You can be mentally healthy and be angry — and in fact, expressing anger can be a really important move for maintaining mental health.

And for another thing, ok, so I do have a mental illness. I am “crazy.” Does that mean my opinion or my voice doesn’t have legitimacy? That’s nonsense. You can be someone with a mental illness and have really important stuff to say, and you can be someone who doesn’t have a mental illness and be plain wrong, or mean, or bad.

Which becomes really important when we start talking, for example, about the false association between mental illness and violence.

MG: That’s a great point. Mental health needs to be completely detached from questions of a person’s credibility. In our postmodern world where ad hominem is the predominant form of argumentation, the way you prove someone else is “wrong” is to show how “unhinged” they are.

DH: Yeah, I think that’s true. And I think, too, that people are different, right? So for me, I’ve learned that if I, for example, get into a heated debate online, that that’s going to be hard for me to maintain my own sense of health and wellness in relation to that conversation. I have to be careful about how I manage my emotions in that kind of thing, because they can really come back and bite me in the ass. I don’t know if you’ve heard of spoon theory, which is this way of explaining chronic fatigue and chronic pain. I’ve got a similar thing with my mental and emotional health — I have to watch what spoons I spend, where I invest my emotional energy, because I can really push myself over a certain point of no return with it.

But for someone else, they might have the exact opposite issue. They might spend their days biting their tongue, trying to stay quiet, trying to just go along to get along, and they’re like exhausted from it. And being able to state how they’re honestly feeling, that they’re angry, that they’re hurt, that they’re upset, that might be a really healthy move for them.

People are different, and we’re complex. I think a lot of forums where debates are happening, online in particular, don’t necessarily have the capacity or the space to handle that complexity.

MG: Thank you so much David! Everyone check out his book Christ on the Psych Ward!!!