This article, co-authored by Laurent Dubois (@soccerpolitics) and MMW’s Shireen Ahmed, previously appeared in Sports Illustrated.

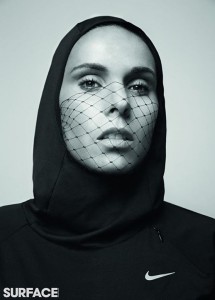

A recent special issue of the French Surface Football Magazine includes this portrait of national team player Jessica Houara-d’Hommeaux. The photograph is an invitation, even an incitement. In contemporary France, the discussion about and policing of what Muslim women do and don’t wear is a national obsession, one of the most electric and illuminating debates in the contemporary Republic. Houara’s striking portrait forces one to think through the layers of symbolism and politics surrounding the participation of Muslim women in contemporary sport in France and beyond.

France started out strong in the Women’s World Cup with a 1–0 defeat of England, but was shocked in a 2–0 loss to Colombia in its second game. Now Les Bleues will likely need a victory over Mexico on Wednesday to guarantee a place in the next round of the tournament.

In the years since its strong run in the 2011 World Cup, the French team has been increasingly celebrated back home. There is, however, a long way to go. The Surface magazine issue critiques the ways in which female players are sexualized—“Do we ask men to be good looking to play football?” asks star player Louisa Necib—and the inequality in coverage between men’s and women’s international football. In the pages of the magazine Les Bleues are presented as strong, powerful and glamorous superstars ready to take on the world. Their portraits show them in athletic gear, training on the pitch, but also in stylish clothes from a range of high-end fashion brands. The first profile is of Houara, whose portrait may be the most striking image in the magazine.

Houara is one of six players of North African background on the French national team. The others are Kenza Dali, Amel Majri, Kheira Hamraoui, the goalkeeper Sarah Bouhaddi, and Necib, one of great stars of international women’s football. With the increasing visibility of the team, these women have become some of the most recognized and visible women of North African descent in France. Necib, the most talented and successful of the group, has been particularly celebrated.

The 27 year-old Houara began playing football at the age of 10 after following her brother to his training sessions and matches. As she explains in Surface, her mother and father (both from Algeria) always supported her playing. She always wanted to make her father, who managed a youth team, proud of her accomplishments on the pitch. An attacking defender, she is a pillar of the professional women’s team at Paris Saint-Germain. One of the top clubs in the world, they played in the UEFA Women’s Champions League finals a month ago.

She has been a force on Les Bleues since 2008. In an international friendly against the U.S. in early 2015, Houara scored her first international goal: a breathtaking cross that resulted in a 2–0 win against one of women’s soccer’s foremost powers. The previous Women’s World Cup saw France finish in fourth place, but this time the 27 year-old is is aiming for a stronger result.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dw_EAg3_9Q4

In the Surface portrait, Houara is wearing a Nike hoodie, wrapped tightly around her head so that it looks like a hijab. As Maria Hengeveld, a researcher at Columbia University who studies Nike’s relationship to women, explained to me in an interview, since its 1995 “If You Let Me Play” campaign, Nike has “actively capitalized on women’s issues and positioned itself as a booster for global women’s participation in sports to corner the women’s market.” At first Nike’s women’s ads were met with skepticism, given that anti-sweatshop campaigns focusing on the corporation were just then confronting consumers with the miserable and abusive conditions of its women workers. But since then, Nike has worked hard to transform its image. Its foundation actively partners with the UN Foundation, USAID, the British Department for International Development and various international women’s rights groups on girl-focused programs in the Global South to promote that message that, as Hengeveld notes, “the picture of Houara also seems to convey: that Nike helps women to challenge the laws and practices that hold them back.”

Nike’s campaigns directed at women in Africa, Hengeveld notes, “present women’s participation in the market economy and on the sports field as gateways to gender justice,” and therefore as a way to “liberate women from the traditional cultural practices that oppress them.” These campaigns conveniently overlook the “fact that the free market and the athletic apparel industry oppress women” too. “The Muslim women who stitch these products in Indonesian factories, generating the profits Nike uses for its endorsements and philanthropic feminist work,” notes Hengeveld, “still make such low wages they couldn’t even afford them.”

Houara’s portrait adds something to the Nike gear: a kind of sort of transparent niqab, one made of the netting from a goal, that covers most of her face. (The netting is used in several other photographs in the magazine, including a portrait of Bouhaddi, the goalkeeper of the team and Laura Georges, whose parents are from the French Caribbean, both of whom wear the netting over their entire heads). This is striking because it is illegal to wear in niqab in public in France. Given the intense debate about this law during the last years, the photograph is an ambiguous but powerful gesture. Indeed, when the photo was posted on Houara’s Facebook page, it immediately incited intense debate and commentary.

The portrait also directly evokes the complicated history surrounding the hijab and international soccer. That story goes back to 2007 at a youth tournament held in Quebec when an 11-year-old girl from Ottawa named Asmahan Mansour was told by the referee that she could not play in a hijab. She, her coach, and her teammates—along with several other teams—protested the decision and refused to play in solidarity with her. But the incident triggered a cascade of decisions with global implications: the Canadian Football Federation referred the matter to FIFA, which decided to ban the hijab from women’s soccer.

The justifications for the ban were never very clearly stated—they included the evocation of the dangers presented by the hijab to players wearing them in competition—but they had a serious impact on some teams. In June, 2011 the Iranian women’s football team was prevented from playing an Olympic qualifier because they were wearing hijab. Jordan’s Prince Ali Bin Al Hussein, a powerful voice within FIFA, lobbied the organization to change its policy. On July 5, 2012 the International Football Association Board determined that women would be allowed to play in international competition wearing certain approved hijab that meet required regulations. The ban was only ended on March 1, 2014, after the end of Women’s World Cup qualifying, though there are no players at the tournament wearing hijab.

The French Football Federation, however, immediately placed its own national ban in place. Female French players are currently the only ones in the world who can’t play in an IFAB-sanctioned hijab. None of the players on the national team so far has protested this decision. But the portrait of Houara-d’Hommeaux raises the question: What if they did? The issue, furthermore, will almost certainly come up again in an international context: the next Women’s World Cup will be held in France in 2019, and Middle Eastern teams like Jordan and Iran will be competing for a place in that tournament. Will they be allowed to wear hijab if they make it?

Houara-d’Hommeaux has offered Eid greetings to followers and publicly supported the historic run of Algerian team (many of whose players grew up in France) at the 2014 Men’s World Cup. But she has not otherwise explicitly stated that she observes Islam. But her portrait for Surface raises fascinating questions: Is Houara making a political statement, trying to create a collision of sports with social issues? Is she advocating for the right to wear hijab in French football? Is her netted evocation of the niqab a critical comment on the country’s laws surrounding the veil, suggesting that they may be as transparent and vacuous as a football netting?

Whatever its intended meaning, the image is beautiful and it is intense. The portrait reminds us that the veiled woman is a celebrated Olympian and a decorated footballer. Can footballers look like this? Should they look like this? Perhaps it is also be a reminder to athletic clothing companies, including Nike (which doesn’t design or manufacture any sportswear catering to headscarf-wearing athletes) to think more carefully about their potential customers.

Given Houara’s Algerian descent, the image does not seem to be about appropriating or parodying the veil. It is not a comment about the oppression of Muslim women. Instead, the portrait seems to be about quietly slaying some misconceptions. After all, it is not often that hijab is associated with athletic achievement and inclusiveness. With the potent image, Houara reminds us that as she speeds and succeeds on the pitch, le voile and les footballeuses are not contradictions.