2012-13 is the Winter of the Pants. Will you join the party?

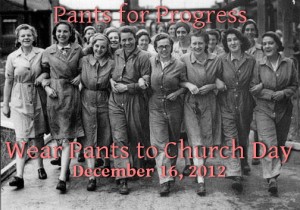

On December 16, 2012, Mormon feminists declared Wear Pants to Church Day, inviting participants to, well, wear pants to church, ‘in solidarity with those of us who seek gender equality everywhere, including the LDS church. And when somebody asks you why you are dressed a little differently, take a moment to tell them. This is our opportunity to make it known: “We are here! We are here! We are here! We are here!”’

The common reaction from the unchurched (or those in mainstream or liberal churches) might be “How can this possibly be controversial? It’s 2012!” But it was controversial. Some women received death threats.

Pants are often pivotal in narratives of feminists escaping patriarchy. Buying my first pair of jeans (in 2006) marked the birth of my new life. Owning a pair of pants made it impossible to pretend I was anything like the girl I’d been raised to be.

Now, Simi Lampert tells a similar story of liberation, this time from the perspective of an Orthodox Jewish woman:

I tried on pair after pair, discarding all of them in indecision, until I was left with one pair that I couldn’t seem to get rid of. Snug but soft, comfortable but flattering, they were the type of faded jeans that seemed like a staple for every other woman’s wardrobe—and now, apparently, mine. So, I threw them on the pile and paid for them. They were mine, and I was a step closer to actually wearing pants in public. It felt thrilling and normal all at the same time. I looked good. I felt good. And I was buying jeans. I felt so … normal.

Jeans, beyond pants, are the essence of comfort, the symbol of the average American. Male or female—it doesn’t matter. If you’re American, you probably have jeans. You wear them to your family football cookouts, or whatever typical Americans do in their free time. When I wore them, I knew I wouldn’t stand out as different from everyone else, as I had for most of my life. I would be like any American girl, wearing her jeans.

When I got home, I suddenly felt nervous all over again, like a teenager afraid to come home smelling of alcohol. I hesitated, then told my mom, “I bought pants.” She turned to my sister and joked, “You corrupted her!” And that was it. Nothing more was said. Once again, I was reminded that I’m 23 and can make my own decisions, something that takes longer to sink in than it should. That step over with, I proudly showed them off to my fiancé, whose only real question was why it had taken me so long to come to the decision he knew I’d wanted for so long.

That feeling of normalcy, and the sudden sense of scandal that normalcy brings, rings true for most daughters of conservative, patriarchal religion who rethink their upbringing. Pants have significance because their absence has significance. Lampert writes:

When I would spot a man with a kippa or a woman in a skirt and long sleeves, there was an implicit understanding, an invisible head nod of recognition that only we could perceive. This social aspect, more than anything, made me appreciate the strict bindings of modesty laws, especially as my social circles grew and I began working outside the strictly Orthodox community.

Not wearing pants was a means of broadcasting group identity, and of finding allies in the sea of human bodies. Evangelical Christian women have set up a “Jean Skirt Girls” facebook page that’s clearly about far more than a simple affinity for the garments. They’re a brand. I wrote about the flip side – the exhaustion of being a walking billboard – in this installment of my story on No Longer Quivering:

Every day, I worked an eight-hour shift at Wal-Mart, and despite my best efforts to vary my wardrobe and to solicit comments on being overdressed rather than appearing strange, inevitably somebody noticed that I didn’t wear pants. “It’s Biblical,” I sighed. It was a shortcut other women had taught me to say when I didn’t want to have a long conversation about my dress. “If they’re thirsty, they’ll keep asking,” my mother and her friends had instructed. Inwardly, I was sick of inspiring thirst.

I felt as though the Holy Bible were plastered to my chest. There was nothing I could do to avoid mentioning it. I began to obfuscate when strangers and friends confronted me. “It’s religious,” I said sometimes. Other times, “I just like skirts.” As I looked around at my coworkers in cute jeans and tank tops, I felt less and less inclined to “witness” and wanted desperately just to go about my business without incurring questions from strangers.

A Sober Second Look also comments on a similar setting-apart phenomenon when she began to wear hijab as a white convert to Islam in Canada:

You could almost see the wheels going around: White woman, with white parents, from here, wearing a Muslim thingummy on her head. This does not compute. What could be the reason for this? Hmmmm…. Oh, ok, I’ve got it!

And then they would ask, “Where is your husband from?”

When I told them, then the puzzlement would immediately vanish from their faces. They thought that they had solved the mystery. My husband must be making me dress this way. Some of them would actually say, “Oh… so you wear this because your husband wants you to.” … I had become a stranger in the land of my birth. I was constantly reminded of this fact every time I stepped out of the house. I didn’t belong here any more. This was not my home now, even though it was the only home that I had ever known.

Simi Lampert has not left behind Orthodoxy; she continues to cover her hair as a sign of her marriage, she writes. Moreover, pants have become her new tzniut, her own personal symbols of modesty. The Mormon women, too, see wearing pants as a statement of equality within their faith rather than a symbolic rejection of it. So I think there’s a deeper truth here. Pants aren’t a symbol of rebellion, but of revolution (as Lampert’s article suggests). They’re about women making their lives and their faith their own.

For me, it meant leaving behind my church – because my church did not fit me. Could I imagine myself as a Christian woman, though, wearing pants to church without discarding the cross around my neck? Certainly, I can. I wear pants to my Unitarian Universalist church – and no, I’m not entirely over feeling surprised that I can. Pants aren’t about rubbing anything in the face of religion. They’re about throwing off patriarchy and owning your beliefs – religious or otherwise – for yourself.

Pants are still symbolic of power in Western culture. Not just power, but personal power. The kind women aren’t supposed to have in patriarchal religion.

Walk on, sisters.